Among demographers, 2023 will be remembered as the year Brazil “shrank” by almost 5 million people.

A new census put the country’s population at 203 million people—well below the 208 million previously estimated by Brazil’s national statistics institute, and even further from the 216 million calculated by the United Nations.

Those missing people didn’t vanish or emigrate—they were never born. The 2022 census, delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic, showed that Brazil’s population grew during the 2010s by just 0.52% per year—half the rate seen throughout the 2000s, and the lowest such percentage since 1872.

Brazil is not alone. For half a century, fertility rates around the world have been drifting downwards thanks to a confluence of rising education levels, greater labor force participation by women, strengthened reproductive rights, and wider access to contraception. But in several Latin American and Caribbean countries, this decline has recently accelerated to an unexpected degree that even experts are struggling to explain.

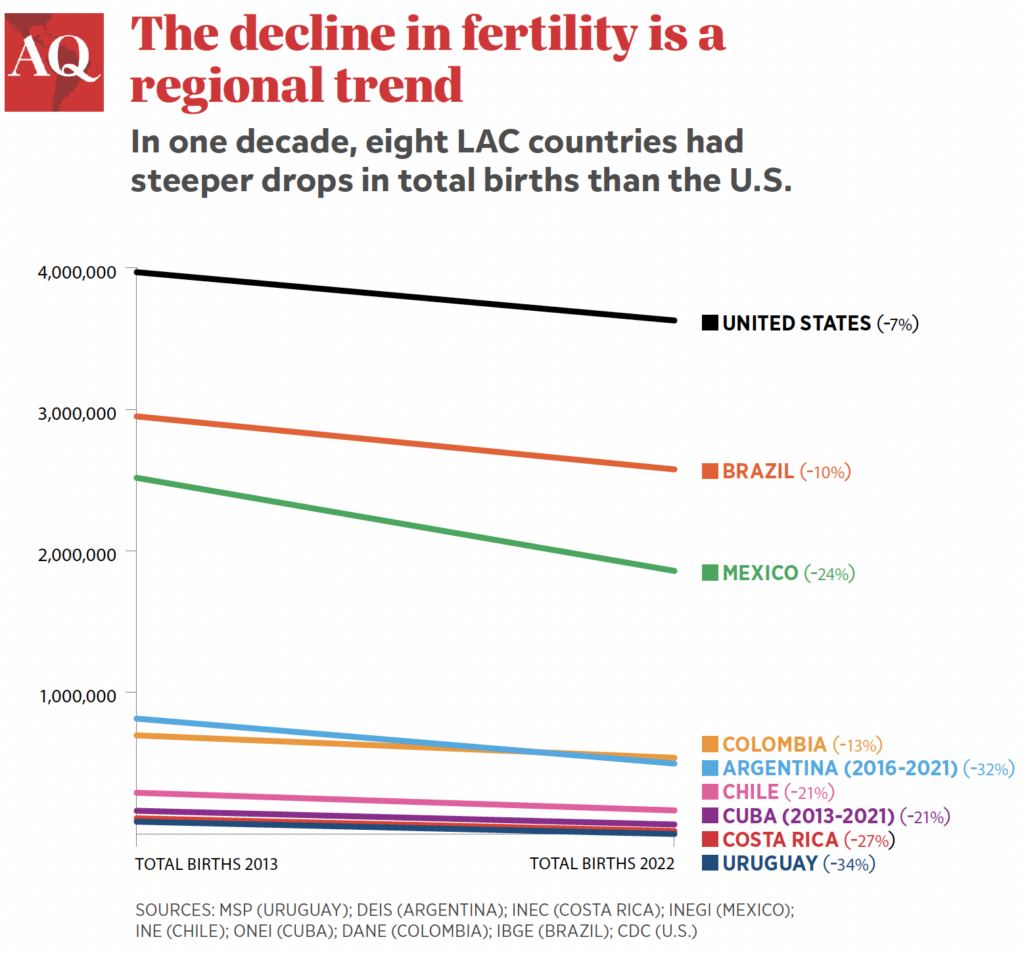

Consider that total births in the United States, which has also seen a sustained reduction in fertility, dipped by 7% between 2013 and 2022. Within the same period, births fell between 10% and 34% in eight Latin American and Caribbean countries that account for two-thirds of the region’s total population.

In a TED talk delivered last year, Argentine economist and demographer Rafael Rofman said that his country’s fertility had declined more in the previous six years than in the previous six decades. As a result, he told AQ, “In 2024, there will be roughly 30 percent fewer 4-year-olds entering Argentine preschools than there were in 2020.”

Luis Rosero-Bixby, an eminent demographer who founded the Central American Population Center at the University of Costa Rica, uses the word “vertiginously” to describe how births are falling in his country, where fertility among native-born women is now approaching just one child per woman. In a recent paper entitled “The Great Decline,” Wanda Cabella and three other Uruguayan demographers write that “in just seven years, the total fertility rate [in Uruguay] dropped from 2.0 to 1.27 children per woman… there is no precedent for a fall of this magnitude in such a short period.”

As recently as 2019, a benchmark study by the United Nations Population Division for 2020 to 2100 forecast that fertility in Latin American and Caribbean countries would stabilize at an average of around 1.75 children per woman in the latter half of this century. Stunningly, except for Mexico, all the countries listed in this graph have already dropped below this level. Uruguay, Costa Rica, Chile, Jamaica, and Cuba now have total fertility rates of around 1.3 children per woman—the so-called “ultra-low fertility” threshold that has only been seen in a handful of European and East Asian countries.

Possible causes

What is going on? Demographers say that Latin American and Caribbean women are finding it much easier to control the timing and number of their children because of expanding access to contraception. The region used to have some of the world’s highest rates of unplanned adolescent pregnancy. Although the number of childbirths to teenagers continues to be high in some countries, government programs have begun to offer a variety of free or low-cost contraceptives to women who could previously not afford them. In Argentina and Uruguay, these programs include subdermal contraceptive implants that last up to five years. Rofman says the rapid adoption of these and other contraceptives contributed to a 55% drop in pregnancies to Argentine women age 20 and younger. In Chile, teen pregnancies have dropped by around 70%. And in Uruguay, Cabella estimates that half of the recent fall in fertility is accounted for by women ages 15 to 24.

Rosero-Bixby posits that young women may also be postponing pregnancies that they still intend to have in the future. If they do have children later in life, “completed fertility” (which counts the average number of children that a woman has throughout her reproductive years) could edge back up towards the levels forecast by the UN. But while the current drop may eventually be seen as an anomaly, it could also herald a new normal. Rosero-Bixby told AQ that these countries could follow the path of Italy and Spain, where fertility dropped to around 1.3 children per woman three decades ago—and has not rebounded.

Demographers also point to social, economic and cultural forces that may be prompting people to delay or forgo family formation and childbearing. Long-standing concerns about employment, housing costs, access to childcare and the gendered division of household labor may be hardening into a general hesitation to have children. Millennial and Gen Z women also appear more likely than their mothers to prioritize higher education, career advancement and personal autonomy. Cabella says that although empirical evidence about these shifting norms is patchy, she suspects they are important drivers of recent fertility declines.

Whatever its causes, demographers are not necessarily alarmed by this phenomenon. “Declining fertility is one of the best indicators of social development,” says Rofman. “It’s an indicator of equity, of women being empowered, so we should welcome it.”

Youthful no more

Rofman and Rosero-Bixby also believe that shrinking cohorts of schoolchildren offer governments an unexpected opportunity to improve the quality of education. Costa Rica currently invests more than 6% of GDP on education—far more than any other Latin American country. But Rosero-Bixby estimates that at current birthrates the country’s student population will have dropped from 1 million in 2002 to just 320,000 in 2075. He and Rofman both argue that governments should already be redirecting education budgets to tackle their countries’ notoriously poor learning outcomes. “Education ministries ought to use declining enrollment to improve teacher-student ratios, extend hours of instruction or obtain additional training to teachers,” says Rofman. “Instead, they’re still focused on building additional schools. They don’t seem to be aware of the demographic shifts.”

Rofman argues that prioritizing better education outcomes is urgent because countries will need to sharply increase productivity if birthrates remain low, both to ensure prosperity and to enable governments to finance social services and pension obligations. Economists have long warned that the old-age support ratio (the number of working-age people relative to the number of retirees) may not be sufficient to sustain the region’s already-underfunded pension systems in the years ahead. Rosero-Bixby estimates that at current fertility levels, Costa Rica’s support ratio will drop from the current seven workers per retiree to just one by 2075. “There does not appear to be a realistic demographic answer that will prevent a collapse of the pay-as-you-go pensions system,” he writes. Rofman is more sanguine on this point. With improved life expectancy enabling people to work longer, he thinks more countries will follow Uruguay’s recent example and raise the retirement age, while productivity gains and technology will also cushion the blow.

In either scenario, it may be time to abandon the long-held assumption that a youthful, fast-growing population is one of Latin America and the Caribbean’s great competitive advantages. One prominent Brazilian demographer recently warned that if current trends continue, deaths could exceed births in his country as soon as 2035. While the “demographic dividend” may still pay off, the deadline for attaining it might be right around the corner.