FLORIANOPOLIS, Brazil — A few weeks ago in Mexico, Julio Almanza, head of the business chambers’ federation in Tamaulipas state, went on television to say that drug cartels were extorting local businesses. Days later, he was shot to death outside his office.

After decades of failed repressive anti-drug policies in Latin America, armed groups have expanded their grip far beyond narcotrafficking and now have their hands on vast amounts of land, agriculture, oil and politics in the region. They increasingly operate in a gray zone between legal and illegal business, making it harder to track the source of dirty money.

The evolution of three different armed groups in Mexico, Brazil and Colombia clearly shows how this process is occurring in the region today.

The consequences are immense: Last year, Latin American and Caribbean countries were home to more than 40 of the world’s 50 most murderous cities. As the latest UNODC report on homicides contends, nowhere are homicides caused by organized crime more widespread than in this region. Organized crime is blamed for half of homicides in Latin America and the Caribbean.

In Colombia, about 24,000 combatants are now part of both armed groups and organized crime groups. In Mexico, according to International Crisis Group analysis, the number of criminal groups doubled between 2010 and 2020, reaching more than 200. Moreover, in Brazil, the migration of drug gangs to the north and northeast led to a process of factionalization: Today, more than 72 criminal organizations are said to operate throughout Brazil. Altogether, the data suggest a new paradigm to counter these groups is urgent.

Brazil’s case

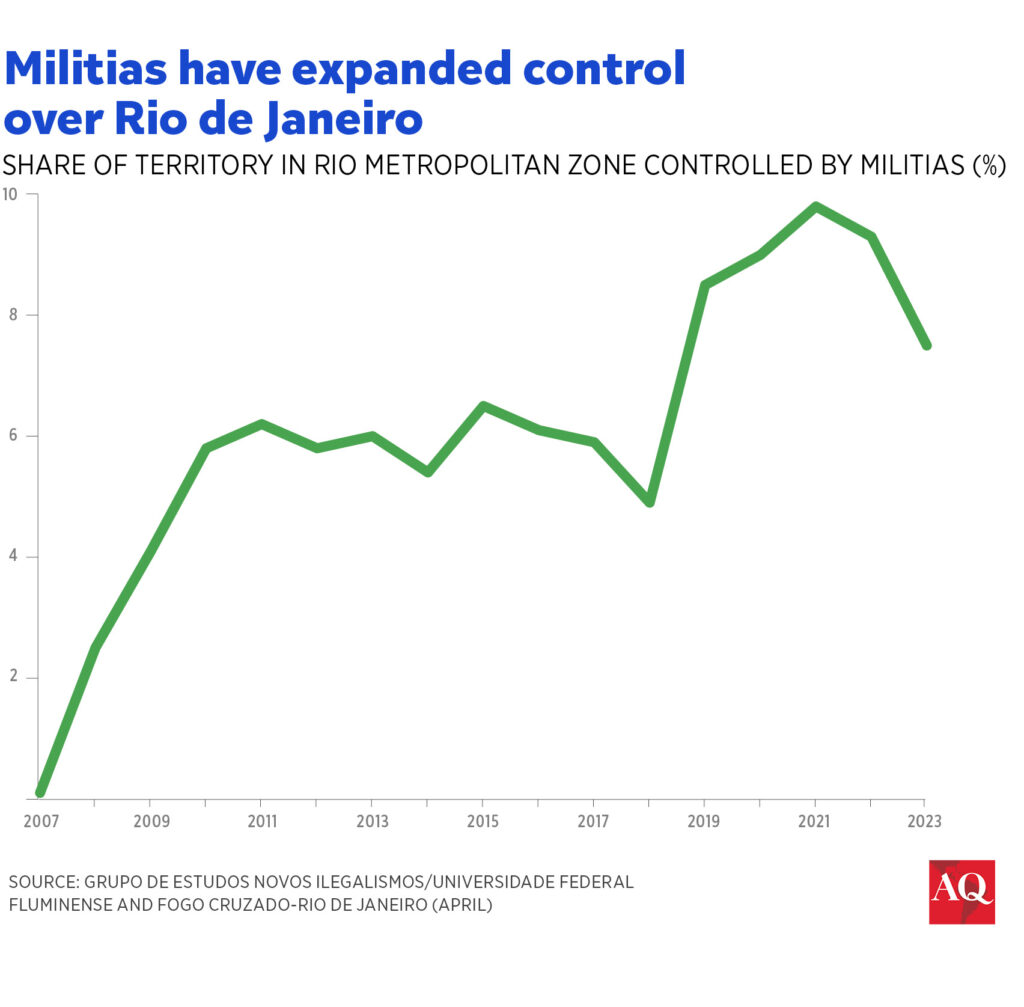

Milícias in Rio de Janeiro are a typical example of state agents engaging in illegal business. These groups, largely composed of police and law enforcement agents, illegally control vital services in certain neighborhoods: electricity, cooking gas, drinking water, cable TV transport, and even housing. Extortion practices are widely known and impact the local economy, based mainly on informality. Some communities are charged a monthly fee per house for security services against petty crimes. The thriving business of illegal land grabbing has also become a key source of money.

But increasingly, milícias have also strengthened connections to the international drug trade. Recently, a group of milícias known as 5M joined forces with the drug gang Terceiro Comando Puro to fight off their common competitor, Comando Vermelho, which is the largest and oldest drug trafficking group in the state. Milícias control drug selling in their territory and do not allow other groups to compete with them.

They also embody a political project, acting to make sure candidates they support are elected. Milícias use different tactics for this end. Neighborhood associations are controlled to support miliciano candidates during elections, who end up winning with a disproportionate share of votes. There are also reports of intimidation. This year, regional electoral authorities will change the location of some voting posts to help bypass their effect. A study found that voters in areas controlled by milícias cast their ballots slightly differently from those in other places – in 2022, they supported more right-wing candidates.

Mexico’s turf

In Mexico, the eruption of Los Zetas in northeastern Tamaulipas was a watershed in the late 1990s. First enlisted by Gulf Cartel leaders, they initially encompassed a small group of Mexican army deserters who were well-trained in military equipment and, therefore, exemplified a military style of operation.

Researchers estimate that Los Zetas control about 40% of the market for stolen oil, mainly in the states of Tamaulipas and Veracruz. The crackdown on drug organizations during Felipe Calderón’s government (2006-2012) motivated them to diversify to less visible activities to evade repression. After their top leaders were executed or arrested by counter-drug efforts in Mexico, from 2015 onwards, Los Zetas split into several other factions.

At the border with the U.S., the weakening of the once-dominant Arellano Félix organization helped its rivals. Groups such as Cartel de Sinaloa, Los Zetas, Los Güero Chompas, Cartel del Noreste, and Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG) are now disputing Plaza Tijuana with the remaining cells of Arellano Félix as homicide rates soar.

Competition between Mexican drug organizations spilled over into Ecuador, leading to a spike in violence as the country became a transit route and production center for cocaine paste in recent years. Whereas Ecuadorian authorities assert Cartel de Sinaloa supports Los Choneros (considered the major drug organization in the country), Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación is on Los Lobos’ side, both providing them with weaponry and money and therefore fueling violence.

Colombia under BACRIM

In Colombia, the demobilization process (2002-2006) formally dissolved the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (a federation that comprised most paramilitary groups at its height). Governmental action was, however, unable to prevent AUC from factionalizing. Unlike drug gangs that are ultimately profit-seeking, paramilitary groups are political armed organizations. Yet, the line between them and criminal groups is increasingly thinner in Colombia.

Paramilitary groups today are known as BACRIM (bandas criminales – or criminal groups). They still operate mainly from local communities, acting as a local authority in solving community conflicts to increase their popularity. Unlike their predecessors, they have expanded into a more extensive set of funding sources unrelated to the drug trade, from selling daily consumption items (milk products, eggs, arepas and soft drinks) to illegally mining gold and silver. Yet, the drug economy remains the primary driver of their operation.

Alliances with members of the police, military forces, judges, and other state agents are vital in maintaining their territorial control. The Clan del Golfo (or Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia, as they prefer to call themselves) is known to be the largest one, controlling the most significant portion of drug exports in Colombia (about 60%), with 51 regional commands. However, BACRIM, unlike the previously mentioned AUC, do not have a unified command. Paramilitary groups are reported in 31 out of 34 Colombian departments.

Data and years of efforts to control these organizations suggest that increasing the efficiency of police investigation and intelligence services is crucial to dismantling criminal power. Police reforms have been overlooked for decades, favoring a tough-on-crime approach that ignores the complexity of organized crime. It is time that harm reduction drug policies become the region’s new paradigm for state action.

—

Anaís Medeiros Passos is associate professor of sociology and political science at Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC).