This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on millennials in politics | Leer en español | Ler em português

It’s already starting to happen: Millennials are taking over Latin America. Our generation now accounts for 23% of the region’s population, or roughly 155 million people, making this the largest youth bulge in decades. The youngest millennials are 26 years old and the oldest are turning 41 this year, which means they are increasingly in a position to shape Latin American politics and economics. A few, like Gabriel Boric in Chile and Nayib Bukele in El Salvador, are already at the helm of their countries, giving hints as to what other millennial-led governments may look like in the future.

They represent a generation that differs in important, and sometimes positive, ways from our parents and grandparents. With a few notable exceptions such as Venezuela, today’s young Latin Americans have lived most or all of our adult lives in democracy, able to freely express our views and elect our leaders, unburdened by the military dictatorships that were the rule as recently as the early 1980s. We grew up during an era of economic development, falling poverty rates and broader access to education in Latin America, as well as a technology boom that expanded humanity’s horizons at an unprecedented speed.

And yet, that feeling of progress has clearly dissipated in recent years—replaced by economic stagnation, social unrest and a general unease, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Today, unemployment and underemployment are high on millennials’ list of concerns, fueling widespread pessimism about the future. In many countries, the political class has been marred by a seemingly never-ending series of corruption scandals, reinforcing the perception that politics only benefits the well-connected few. Despite elites’ promises to build more meritocratic and egalitarian societies, young people still face discrimination and entrenched class structures in our everyday lives. Across the region, from Chile, Bolivia and Ecuador in 2019 to Colombia, Panama and Mexico more recently, young people have taken to the streets to express their discontent with the political class and living standards in general.

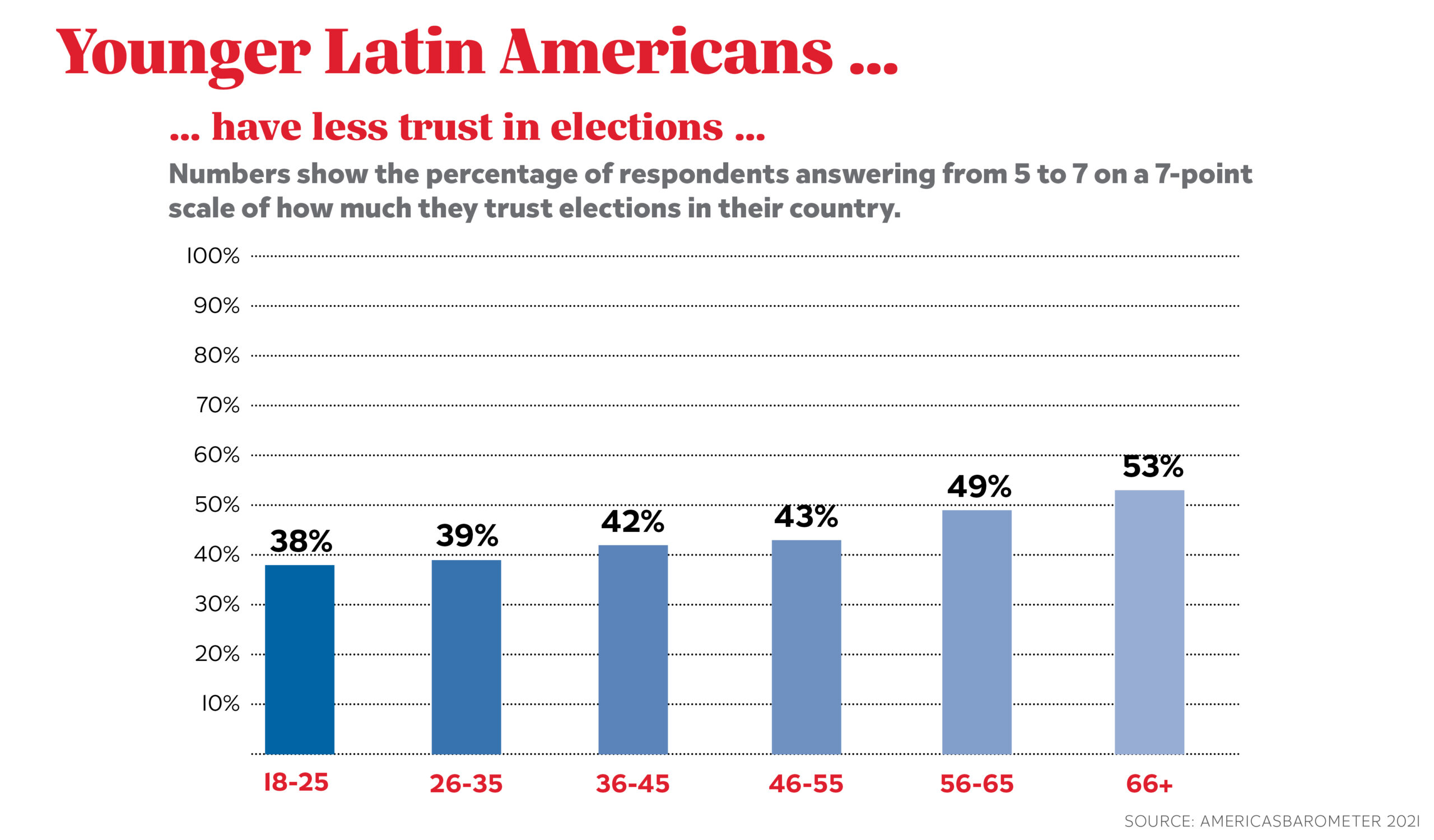

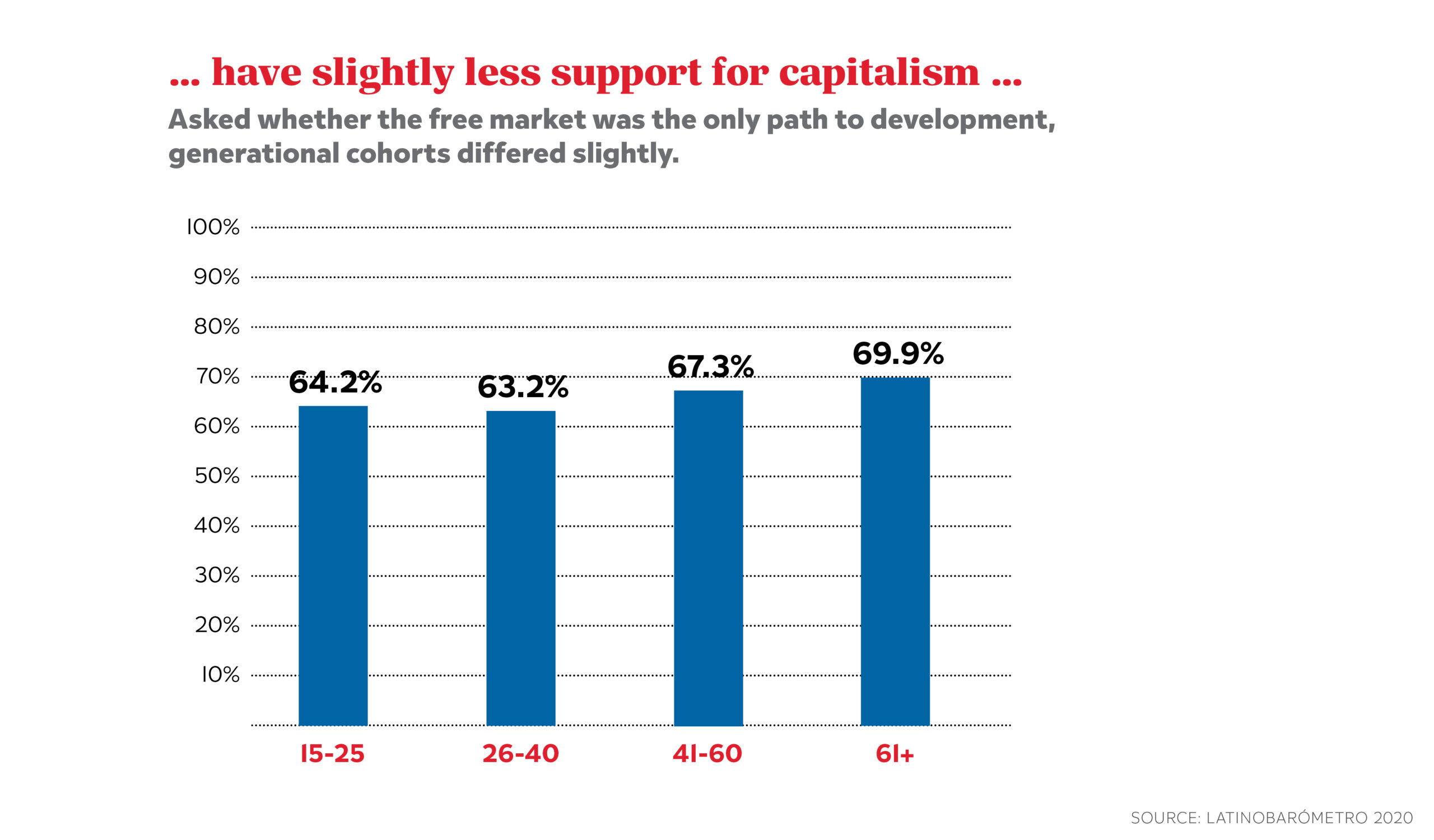

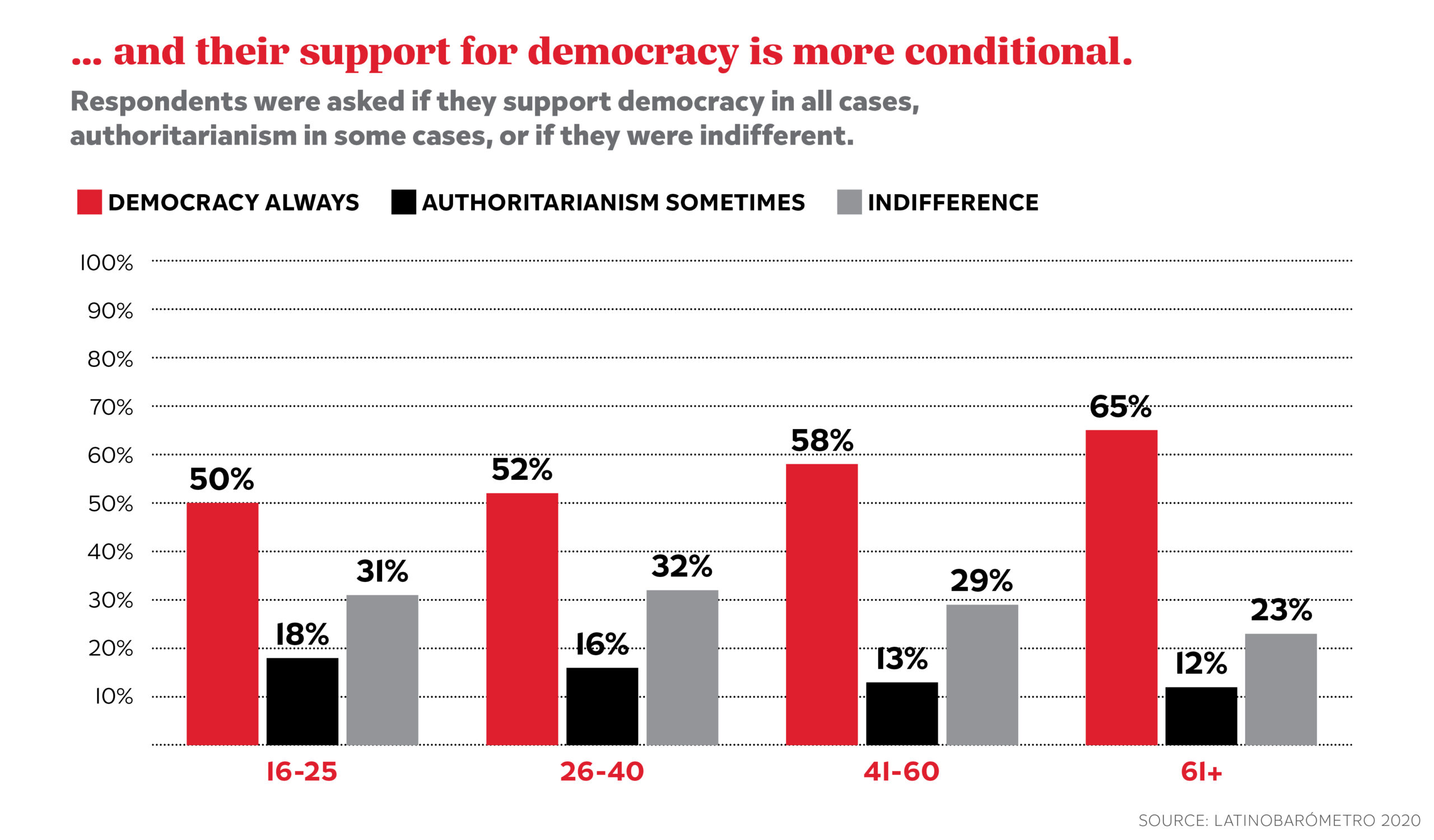

It shouldn’t be surprising, then, that Latin American millennials express higher levels of ambivalence than previous generations toward both democracy and capitalism. Sentiment on such questions varies considerably by country, but according to a major region-wide survey in 2020 by Latinobarómetro, 32% of millennials across Latin America feel there is “no difference” between a democratic and an authoritarian regime. That compared to 29% of people between 41 and 60 who said the same, and 23% of those 61 and older. Meanwhile, nearly a third of millennials disagreed with the statement that “A market economy is the only system with which my country can develop,” compared to 26.1% and 22.7% among the next two older generations, respectively.

There is nuance to these numbers, though. It’s not that millennials are suddenly giving up on democracy in favor of caudillos, or that our generation is being swayed by socialist ideologies and a desire to tear down the capitalist system. A narrow majority—52%—still prefer democracy over authoritarianism in all circumstances, and support for market policies is even higher, at 63%. Even in Chile, which was branded as a bastion of millennial radicalism following the 2021 election of Boric, a former student activist, 55% of millennials report a favorable view of market policies—and voters of all ages recently rejected what would have been one of the world’s most progressive constitutions.

Listen to a conversation with Andrea Moncada on The Americas Quarterly Podcast

So, what is it that Latin American millennials really want from politics? Are we headed toward an era of healthy democracies, or will this generation be tempted by the allure of authoritarian rule? Will priorities such as inequality, climate change and anti-extractivism move to the top of national agendas—or will the status quo essentially remain in place? In search of answers, or at least some insight to these questions, I spoke to a dozen politicians who hail from this generation. These individuals, who are from Brazil, Colombia, Peru, Guatemala, Panama, Argentina, Chile and Mexico, are current or recent officeholders, or are in the process of building a political movement in their countries. Their views range from the progressive left, to centrist liberalism, to right-wing libertarianism.

There were, of course, many differences. But despite their diversity, one overarching theme stood out. All of them believe that their political class, whether on the left or right, has failed on its promise to deliver more equitable and just societies. And that, unless they can quickly succeed themselves, their generation’s patience with politicians—and perhaps democracy itself—may indeed run out. “Young people are among those inclined toward authoritarism, and I can understand why,” Gabriel Silva, 33, a Panamanian congressman who ran as an independent, told me. “There is enormous frustration … enormous discontent.”

Seeking reform not revolution

Many of the young politicians I interviewed said they were called to action by the crises of recent years—and the feeling they could not leave solutions to the older generations. For Tabata Amaral, 28, a federal congresswoman for the Brazilian Socialist Party (PSB), it was the 2013 protests against inflation and stagnant living standards in Brazil. Thirty-year-old Samuel Pérez, Guatemalan congressman for the center-left Movimiento Semilla, credited 2015 demonstrations against corruption in Otto Pérez Molina’s government, when he was still a university student, as his watershed moment. Eduardo Leite, 37, the former governor of Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, said that the Lava Jato corruption scandal of the 2010s tainted an entire generation of older politicians—implying the task was left to figures in his own age group. And Álvaro Zicarelli, 40, foreign policy advisor to Javier Milei, the libertarian Argentine presidential hopeful, was spurred by what he described as the overly burdensome COVID-19 restrictions in his country.

All of those I spoke to overcame major barriers to entry—including their own distaste for the profession. “I always had a very negative view of politicians. I felt disappointment, even disgust,” said Mauricio Toro, 39, a former Colombian congressman for the Partido Verde who served between 2018 and 2022. Luis Donaldo Colosio, 37, the current mayor of Monterrey, Mexico, wasn’t originally comfortable with the idea of participating in public service despite getting offers from parties from an early age, and only warmed up to it after working for years as an advisor to his small political party, Movimiento Ciudadano.

Despite this distaste with the status quo, most of the young politicians I interviewed did not speak in terms of radical, structural economic and political change. While they seek to renew their national politics and economics, this transformation—contrary to the stereotypes held by older generations—isn’t framed in revolutionary or even particularly ideological terms. This may be because they feel that enhanced economic opportunities, better quality education, the protection of individual freedoms and social inclusion are simply their natural rights. Indeed, the picture that emerged is that millennials haven’t stopped believing in the ideals of democracy and the market. They are frustrated with how these have worked in practice, and want to improve the current system, not replace it.

Indeed, the demands I heard were more pragmatic in nature. Eliminating corruption was a common theme, as well as better access to employment and educational opportunities. “Most young people don’t support a radical agenda (in Panama). They are interested in specific issues,” said Gabriel Silva. Pedro Kumamoto, 32, a former state legislator and a current city councillor in Mexico’s Jalisco state, finds there is a generalized anxiety among his generation regarding very material concerns, like housing, working hours, retirement and social security. In other words, “what the previous century’s revolutions supposedly gave us.” These are needs that are “common sense” for Ana Martínez Chamorro, 34, member of the Chilean party Revolución Democrática.

“I always had a very negative view of politicians. I felt disappointment, even disgust.”

The main way to achieve these goals, according to the politicians I interviewed, is to ensure that Latin America’s political class actually fulfills its representative function. “The biggest problem (in Brazil) is politics’ disconnection with the people,” said Amaral. In Colombia, traditional political parties make decisions that have nothing to do with the reality that voters experience, agreed Toro, fueling a generalized distrust. Across the region, younger generations do not see themselves reflected in party politics and want to see the old political class replaced. After Peruvian President Martín Vizcarra was impeached by Congress in 2020, a move considered highly corrupt and undemocratic by the majority of the country, it was mostly young people who took to the streets to protest, chanting: “The dinosaurs are going to disappear.”

These concerns seem straightforward. It’s hard to disagree with providing young people with better opportunities in life. Demanding more political representation is not, at first glance, a controversial issue. At least theoretically, democracy is about providing a seat at the table to all groups in a society. But while Latin American millennials might think their demands are sensible, they face a significant challenge: The elites that have ruled Latin America for decades don’t have much incentive to change the status quo.

Systemic challenges

To understand why requires looking at the last three decades of Latin America’s history. As recently as 1977, there were just three true democracies in the region: Costa Rica, Colombia and (ironically) Venezuela. Today, by contrast, more than 90% of the region’s population lives in democracies, although many of them are backsliding or under threat. This transition has seen its share of progress: Social movements supporting causes like Indigenous representation, gender equality, access to abortion and the protection of sexual minorities have successfully campaigned for more political and socioeconomic rights. And yet, as the saying goes, the more things changed, the more they stayed the same. Despite the election of left-wing governments in the early 2000s that sought to increase the role of the state in the economy after years of structural adjustment policies, and that promised to bring about social justice for the underprivileged, Latin America’s oligarchic tendencies and high levels of inequality remain.

One explanation for this is that democratization in the region was largely a top-down, elite-controlled affair. In Brazil and Peru, military juntas were able to leave power largely under their own terms, and retain a degree of influence that helped protect the status quo. The end of the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship in 1990 saw the return of many of the same figures, including Presidents Patricio Aylwin and Eduardo Frei, who had been prominent in Chilean politics prior to the 1973 coup. Elsewhere too, including Argentina, governing returned to the hands of those elites that had been in charge before democracy was interrupted, and they often chose political stability over large-scale reform.

Another barrier is that Latin American economies are built in a way that entrenches inequality. Driven by the commodity boom of the 2000s, countries doubled down on primary resource extraction, like mining, gas and oil, as their main source of wealth. But these are not labor-intensive industries, and so elites have little reason to invest in their workforces. Leftist governments relied on limited-impact welfare policies like conditional cash transfers, which targeted populations in extreme poverty. But the measures that would more widely transform people’s living conditions, like tax reform, tertiary education reform or streamlining labor markets, either went against elite interests or were unpopular among the population.

In other words, millennials have inherited a political and economic structure that is stacked against them. Those who now seek to improve the system face an additional obstacle: Party systems in the region have turned increasingly rigid in the past two decades. In the 1980s and ’90s, countries generally had low requirements for registering a political party, in terms of signatures, the number of affiliates, electoral thresholds to avoid legal cancellation and so on. This was because during democratic transitions, parties became fundamental and were considered a way to channel citizens’ political views. But since then, political elites have tried to retain power, and prevent fragmentation, by closing their party systems and making it harder to create and register new political movements.

“The biggest problem (in Brazil) is politics’ disconnection with the people.”

This is a particularly difficult issue for today’s young politicians, who often do not want to run under traditional parties considered unpopular and lacking in legitimacy. The politicians I spoke to reported significant, and sometimes astounding, bureaucratic obstacles in the path to building their own movements. Guatemalan legislation, for example, formally requires parties to present 25,000 signatures for registration, but Samuel Pérez told me that since the electoral board usually rejects around 80% of the signatures presented, Movimiento Semilla had to present 100,000 signatures in total to reach the threshold. Each signature also had to be certified by a lawyer. In Mexico, Kumamoto’s party, Futura, was required to hold 88 municipal assemblies—each one of which each needed to have at least 0.2% of Jalisco state’s population present. Indira Huilca, 34, a former Peruvian parliamentarian elected in 2016, pointed out that while Peruvian legislators removed the registration requirement of 100,000 signatures, parties now need to have committees in at least two thirds of the country’s regions, and in no fewer than a third of the provinces. Young people may have the enthusiasm and drive to participate in politics, but as newcomers they usually lack experience and resources, making it hard to navigate tangled legal systems.

Even if millennial politicians make it through the bureaucratic hurdles and manage to get elected, keeping an anti-establishment posture and remaining above the fray is almost impossible over time. In Peru, former congresswoman and two-time presidential candidate Verónika Mendoza was once considered an exciting progressive newcomer. But that began to change after her party, Nuevo Perú, formed an electoral alliance with leftist hardliner Vladimir Cerrón in 2019, provoking dozens of party members to resign in protest. After participating in President Pedro Castillo’s government, Nuevo Perú is now seen by many Peruvians as just another corrupt, self-interested party. And the ultimate cautionary tale in this vein may be Boric—who took office in March as the exciting face of a new generation, and then saw his approval rating fall into the 30s barely a month later, as he was unable to tackle problems like inflation, crime and political deadlock.

“Most young people don’t support a radical agenda (in Panama). They are interested in specific issues.”

Social media and democracy

Even the tools that are supposed to favor millennial politicians may actually be working against them. Latin America has some of the world’s highest rates of usage for platforms like Facebook and Twitter. Some millennial politicians, such as Huilca, Silva and Toro, believe that these tools make them more attuned to the electorate than their older peers. “Young politicians are better at connecting with people’s real needs, better at engaging through social media,” said Toro. But there is little evidence that social media fosters effective forms of political engagement like voter turnout. In fact, studies in Europe have pointed to the opposite: Internet usage has lowered turnout in Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom.

In fact, it’s pretty clear that social media has a negative impact on individuals’ evaluation of democracy. The 2018 AmericasBarometer report indicates that only 37.7% of heavy social media users in Latin America were satisfied with democracy, compared to 43.8% of non-users. The former also report less trust in institutions like the justice system, parliament and elections. This doesn’t necessarily make them authoritarian—social media users express higher support for democracy as an ideal—but the constant exposure to information makes users hyper-aware of the flaws in their political class, especially when these platforms also function as their main source of news. Social media can also exacerbate polarization among the political elite, according to Pablo Argote, a researcher at Columbia University who studies the political effects of social media. He has found that in Chile, political elite interactions on Facebook in the past 10 years pushed them toward more extreme views because negative and angry posts were more widely shared. In such an environment, it becomes extremely difficult for politicians to pass minor legislation—much less tackle difficult, urgent priorities such as climate change.

We are already witnessing what happens when a young politician combines social media with an authoritarian, populist style of governing. Bukele, El Salvador’s controversial president, has been described as the world’s first authoritarian millennial because he has built a modern personal brand through social media that allows him to disregard democratic institutions. He speaks directly to both the population and his officials on platforms like Twitter, making him seem transparent and personable, traits that are valued by voters disillusioned with politics and especially by young people. But at the same time, his strong support—approaching 90% in some polls—has emboldened him to make authoritarian moves such as ordering troops into parliament to pressure legislators into approving a security bill.

Democratic over personalistic leaders

Indeed, some worry that Bukele represents the future in Latin America; that his corrosive brand of politics will win over adherents who see institutions as hopeless bastions of self-dealing elites, and place their faith in supposedly pure individuals instead. They point to other personalistic leaders including Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro, Mexico’s President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, and Argentine congressman Javier Milei, and say this process is already underway. If economies remain damaged in the wake of the pandemic, and social media continues to drive polarization and make compromise impossible, their millennial successors may become even less democratic in years ahead.

For that dire scenario to be averted, the region’s political and business elites will have to be convinced that genuine reform—the kind that allows economies to grow, narrows the inequality gap and provides incentives for a green future—is in their interest. Large parts of the population would have to mobilize, not just on social media, but on the streets or through organized civil society, to help ensure such a transition. And though it may sound like a contradiction, citizens will also have to understand that structural change takes time—and give their elected leaders the space to succeed.

It’s a daunting task. But we have seen previous generations of democratically elected politicians in Latin America deliver positive, if imperfect results. Now it’s millennials’ turn to do even better.