This Friday, 36-year-old Gabriel Boric will be inaugurated as president of Chile, joined by a historically young and diverse cabinet. His story has been hailed as a generational shift, as millennials win office throughout the region, with the potential to shake up politics in Latin America and the Caribbean. He takes office alongside a crop of young leaders such as El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele, Bolivia’s recent Senate presidents (Adriana Salvatierra, Eva Copa, and Andrónico Rodríguez), Colombia’s House Speaker Jennifer Arias and outgoing Costa Rican President Carlos Alvarado. Their rise and recent experience provide an understanding of the opportunities and challenges millennials face in delivering change – and what that change could look like.

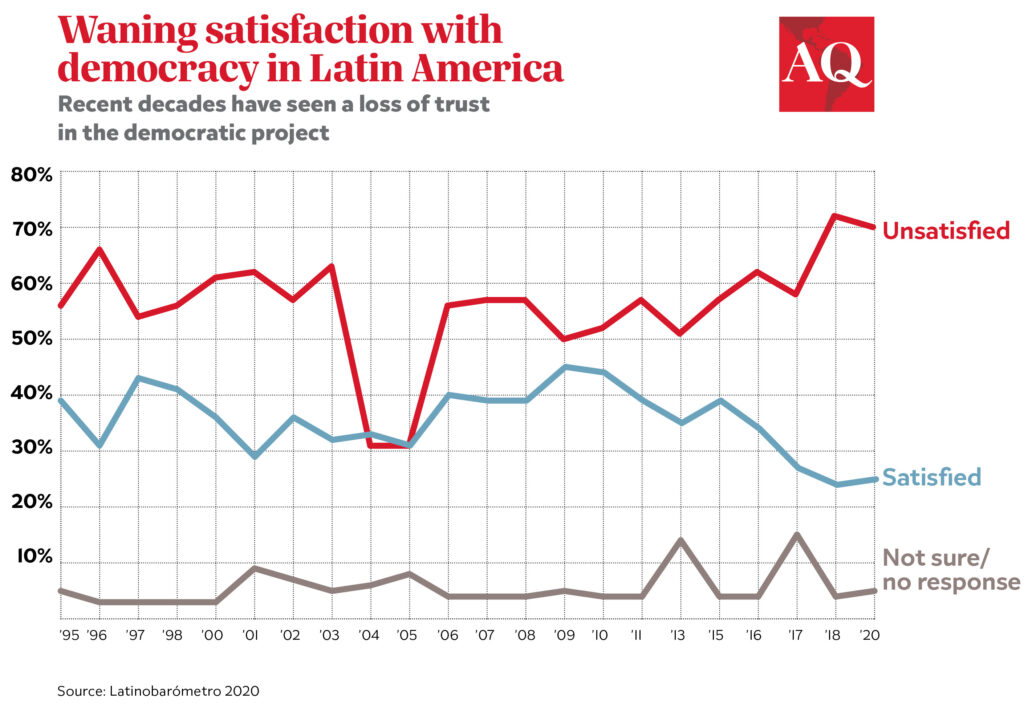

It’s a particularly timely subject, with congressional and presidential elections in Brazil, Colombia, and Costa Rica – and subnational elections in Mexico and Peru – slated for this year. Young leaders elected in this cycle will take office in Latin American countries where democratic institutions are being tested more than they have been in decades. More and more Latin Americans express dissatisfaction with democracy, as shown by Latinobarómetro polling – a stunning level by historical standards, reflective of the COVID-19 pandemic and the inability of governments around the region to mitigate the effects. And in an atmosphere of anti-incumbent sentiment, reflected in part by Xiomara Castro’s big win in Honduras, more young upstarts could find themselves in office with a mandate for change.

But will this generation strengthen democracy – or contribute to declining institutionalism? Will they represent new voices and provide fresh solutions, or will they bring new models of demagoguery, caciquismo and opportunism?

What does change look like?

Most millennial politicians deftly navigate social media in a way that builds a direct constituency independent of political parties. As few have any experience in elected office, they can appeal to voters as outsiders and focus exclusively on issues of most concern to their millennial peers – among them employment and inequality, the environment and gender, racial and LGBTQ equity. Their youth allows these leaders to criticize los de siempre (older leaders and historical parties) for the status quo while avoiding unpopular decisions themselves. Their personal appeal replaces the credibility and brand recognition that political parties once offered. Indeed, that appeal is often curated as anti-party and, by extension, anti-party system.

Nayib Bukele changed his political stripes after being kicked out of the leftist Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) in 2017 and formed his own movement, Nuevas Ideas (New Ideas). Bukele was able to win a broad majority in the Salvadoran Legislative Assembly, which he has leveraged aggressively to the point of generating accusations of authoritarian tendencies from minority parties. But not all leaders will dominate the opposition as Bukele has. Once elected, many will find themselves with weak or fractured political alliances and bitter opposition in the legislature. And while many parties are irredeemably corrupt and anachronistic, the creation of new parties throughout the region has frequently resulted in personalistic vehicles that serve to magnify the image of leaders rather than promote a coherent policy platform. Bukele’s Nuevas Ideas, Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s MORENA party in Mexico, or Evo Morales’ Movement Towards Socialism party in Bolivia serve as warnings of how the decline of historical political parties, and thus checks on a leader’s power, could reinforce democratic weakening.

Millennials across the Americas grew up in a post-Cold War context characterized more by broad democratic opening and market-based economies than by dictatorships and death squads. Many want little to do with the rhetoric of bearded Cuban revolutionaries, right-wing military juntas, or violent narco-militias like the FARC and Shining Path. Boric’s presidency itself grew out of a mass movement in part fueled by rejection of the Augusto Pinochet-era constitution and ensuing economic model. His cabinet seems to reflect as much; his foreign minister served as head of the Inter-American Human Rights Commission and OAS Rapporteur for Nicaragua, where she was a fierce advocate for freedom in that country. His choice for finance minister is well respected in financial circles. Notwithstanding the appointment of Communist MP Camila Vallejo as his administration’s spokesperson, the cabinet is reflective of a less ideological generation.

Challenges to Millennial Leaders

But just because young Latin Americans may be done with Cold War politics, Cold War politics are not done with them. As new leaders use new tools to build new constituencies that cross party and ideological divisions, they will find themselves at odds with enforcers of the historical left-right political dichotomy in the region. This is true on both the left and right, where three stiff challenges to new models of governance stand out: opposition in congress, external actors such as China, Russia and the U.S., and a resistance to change from the old guard.

First, young leaders could face opposition from their legislatures. Chile’s senate is split roughly 50-50, so Boric will need to compromise to get anything done. Hard-left socialist and communist parties are his most likely allies, yet the Communist Party’s rigorous orthodoxy does not always lend itself to expediency and compromise. Boric’s assessment of Venezuela’s dictatorship as a failure evidenced by a diaspora of more than 5 million has generated negative reactions among leftists in Chile and around the region that back dictatorships in Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua.

Second, traditional Latin American parties on the left and right are still highly influenced by external actors that complicate the formation of forward-thinking policy. Leaders on the left must navigate a regional infrastructure that, while broadly supportive of progressive candidates and policies, often supports very illiberal methods and policies. These forums, such as the Grupo de Puebla or TeleSUR, help position anti-imperialism, socialism, and unconditional support for Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua on domestic agendas throughout the region – occasionally to the detriment of other progressive causes.

On the right, links between external actors and counterparts in the region have a similarly stifling impact on political renovation – whether former Trump advisor Steve Bannon’s efforts to support an ethnonationalist, election-skeptical conservatism in Brazil, or the foreign policy activism of Cuban, Venezuelan and other diaspora communities in the U.S. attacking any hint of communism and castrochavismo in the region. On both the left and right, following the economic wreckage of the COVID-19 pandemic, many leaders will be drawn to China in search of loans and no-questions-asked infrastructure investments, often with extortive terms. This tendency will empower corruption and autocratic tendencies in leaders of all political stripes and curb political renovation.

Third, the progressivism of today’s young leaders clashes with the conservatism of the old guard. Many emerging progressive leaders on the Left do not identify with old-school anti-imperial leftist orthodoxy that blames the United States for everything and is obsessed with economic and natural resource nationalism. They take issue with the Castro regime’s reeducation camps for homosexuals or Evo Morales’ reputation for misogyny, or former Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa’s support for oil extraction in virgin rainforests.

Candidates like Yaku Pérez in Ecuador or former Senate President (now Mayor of El Alto) Eva Copa in Bolivia expose contradictions between the “21st century socialism” left’s rhetoric and its behavior. As a result, they find themselves marginalized from the mechanisms of power (as Copa was by former Bolivian President Evo Morales). Or they get pulled into pitched battles against the orthodox leftist establishment of the last 20 years (as Pérez was in his campaign against Rafael Correa acolyte Andrés Arauz). In Colombia, former guerrilla fighter and now Senator Gustavo Petro, leader of Colombia Humana and the leading candidate for president in this year’s elections, saves some of his harshest criticism for erstwhile center-left politicians, like Bogotá mayor Claudia López, who oppose his divisive and authoritarian tendencies.

On the right, the dynamic is similar. Young leaders face entrenched power structures, and with it a resistance to change even in their own political parties. In Colombia, President Iván Duque – young, at 45 years old, but not millennial – has been unable to unite the Democratic Center Party around his agenda. Elected as an “extreme centrist” but with the critical support of conservative former president Álvaro Uribe, Duque has frequently found himself at odds with members of his own party vying for the uribista mantle and has occasionally clashed with Uribe himself.

In Paraguay, the powerful conservative Colorado party, which has dominated all but one presidential election over the last 70 years, is effectively the only vehicle for young right-leaning politicians. Up-and-comers, including those competing in last October’s municipal elections, must associate themselves with current President Mario Abdo Benítez or former president Horacio Cartes if they are to succeed. Another similarity with the left, when it comes to confronting the old guard, is the symbolic pull of the past. Leaders such as Jair Bolsonaro have to some degree resuscitated nostalgia for the military dictatorships of the 1970s. In Peru, Keiko Fujimori leaned heavily on memories of her father’s conquest of hyperinflation and the Shining Path during her several electoral campaigns while in Colombia, former President Uribe was able to cash in on his own legacy to help get Juan Manuel Santos and later Iván Duque elected president.

Stalemate or Dominate?

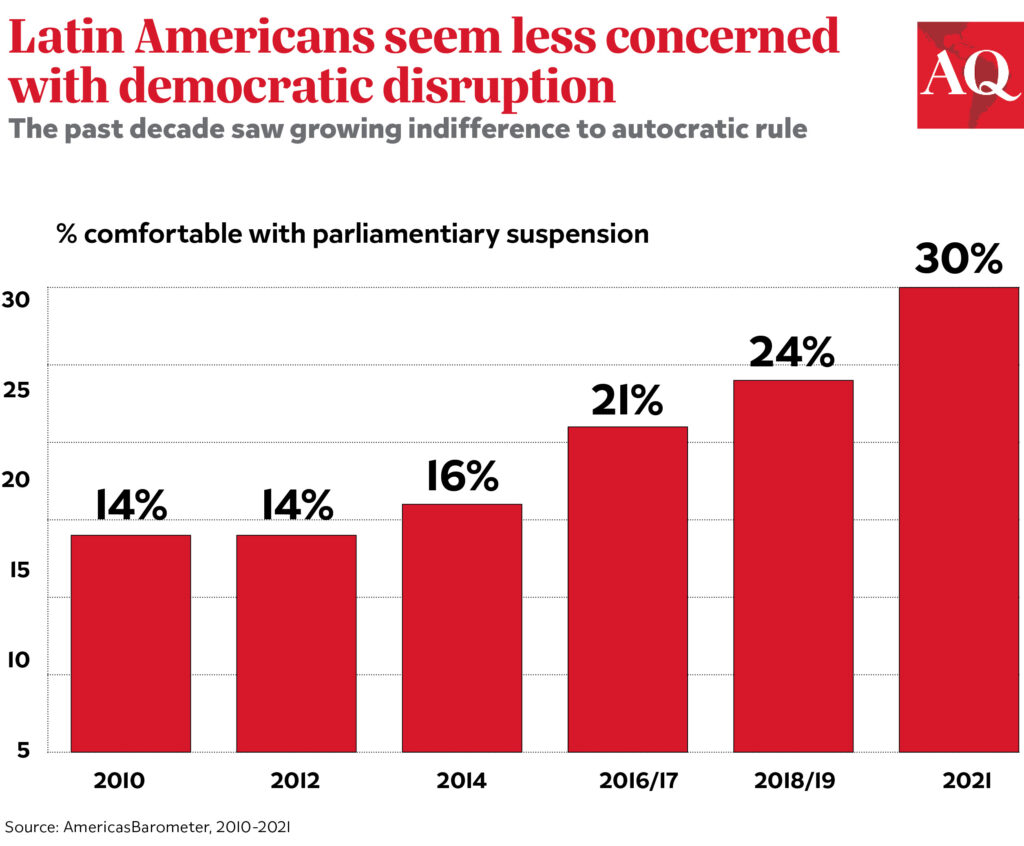

In a context of polarized politics in the region – for example, in Brazil, Colombia and Peru – compromise is increasingly difficult. Young leaders, especially presidents, face stalemate or find they must dominate the system. Worryingly, the 2021 AmericasBarometer survey found increasing tolerance for military coups and strong executives regionwide.

But there is another option for political leadership: Build a constituency that crosses old left-right divides by focusing on issues that matter to young voters. This process should start with political parties. Party platforms around the region are in desperate need of an update and young party members can have a leading role. Platforms should reflect strong positions on issues youth care about – employment, but also climate change and the environment, corruption, housing, education and crime.

This is an area where international development aid can help. Political party institutions such as the International Republican Institute, the National Democratic Institute and others can provide tools and strategies for youth inclusion. This should include help to parties in building their own networks and connecting with likeminded statemen – and women – around the region and beyond. These politicians will need hard skills and tools for governing and legislating to help young leaders transition from activism or protest to running for office and governing. Critically, nonprofits should also support the inclusion of marginalized voices in political parties – not just promoting their “issues,” but giving them a seat at the table.

Parties must expand their reach beyond national capitals and cities to incorporate Afro-descended, indigenous, LGBTQ, and female voices, regardless of party or ideology. But this process can’t be top-down. Millennials and Generation Z won’t simply be given congressional seats: They must prepare early to make successful runs.

If the temptation is for young presidents to dominate the opposition and undermine institutional checks on their power, the response must be to strengthen those institutions. There is no better way to do so than make those institutions, especially the legislature, relevant to and reflective of younger generations. High-profile wins for young leaders such as Boric are necessary but insufficient to really shake up politics. They require generational peers in congress, in local office, in the judiciary and electoral organs to modernize and help democracy deliver in Latin America.

—

Cagley is the International Republican Institute’s Resident Program Manager in Bogotá.