This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on A (Relatively) Bullish Case for Latin America

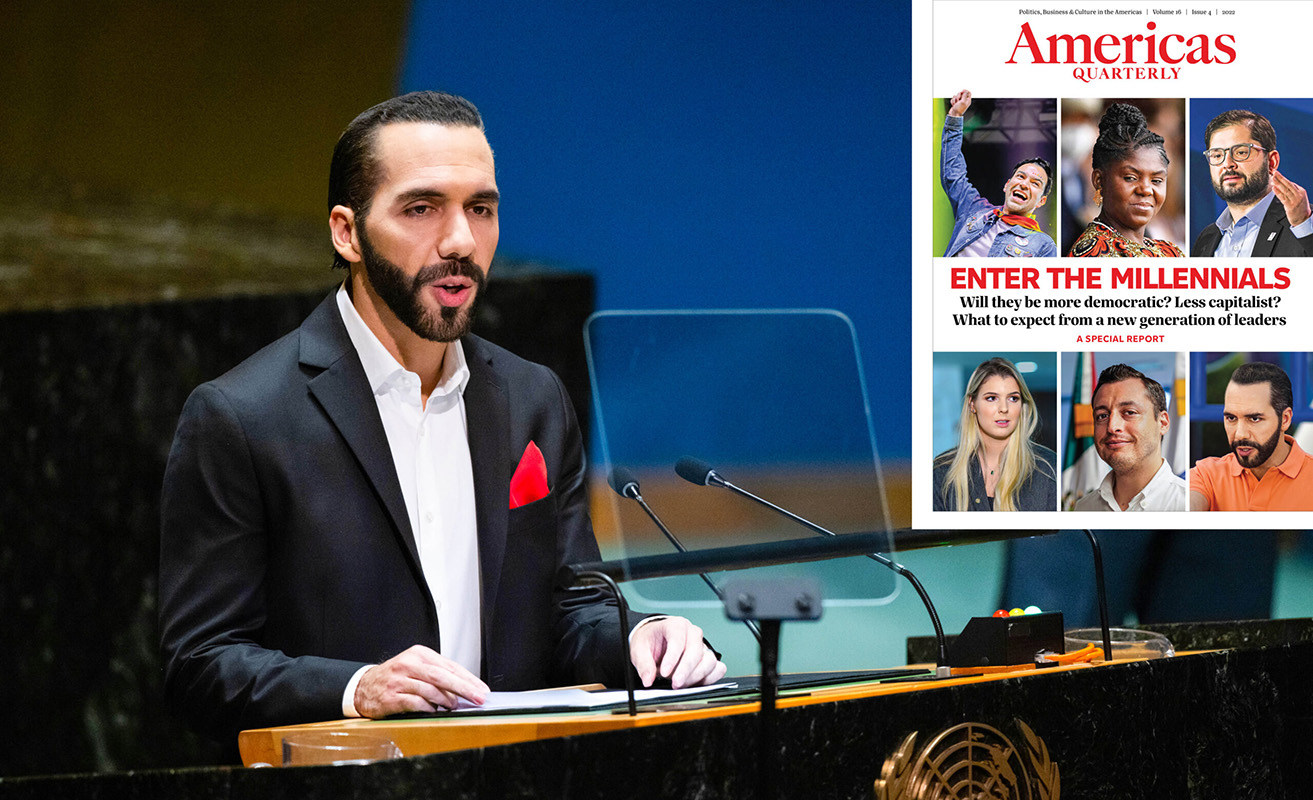

A year ago on the Americas Quarterly Podcast, I was asked who I thought was more likely to become a model for millennial politicians in Latin America: Nayib Bukele of El Salvador, or Chile’s Gabriel Boric. As the first millennials to reach the presidency in the region, they are examples of what the future could bring. And they’re starkly different: Bukele is implementing mano dura policies without regard to the cost to human rights and constitutional order. Boric represents social demands for change through democratic means, emerging from a student protest movement.

It’s hard to compare two such different countries. But I answered that ultimately, Bukele was the model most people would support—if problems like weak political representation and inequality of opportunity weren’t tackled first.

Unfortunately, this possibility is now becoming a reality, as more Latin Americans lose patience with democracies (and political classes) that haven’t become more inclusive, just or equitable. Recent events signal the region might be at a critical juncture between a continued democratic trajectory and erosion towards authoritarianism.

This year’s Latinobarómetro report, published in July, shows that less than half of people now support democracy above any other form of government, a 15-percentage-point difference with the 64% reported in 2010. More than half say they wouldn’t mind if a non-democratic government took power, as long as it solved problems. Young people are the least likely to agree that “democracy is preferable to any other form of government.” Support for democracy is firmest among those over 60.

Latin Americans are increasingly fed up with their elected leaders. This is fertile ground for authoritarianism. The Salvadoran president is an example of how receptive populations can be to undemocratic politicians who know how to connect with citizens through what most concerns them. In the case of El Salvador, that’s security. Bukele is the result of years of lawlessness and violence fueled not just by the MS-13 and Barrio 18 gangs, but by previous governments’ inability to bring the country under control. He presents his tough-on-crime policies as “common sense,” and Salvadorans feel that he has delivered. No matter that they have resulted in thousands of human rights violations.

Gabriel Boric was also successful in connecting with Chileans at the beginning of his presidency by promising to dismantle political and economic inequality. But his administration struggled when the progressive left overcorrected, proposing a constitution too focused on identity politics that demanded changes beyond what the population wanted. After shifting the government’s focus to tackling a surge in crime, an issue most Chileans now say is the most pressing problem in the country, Boric’s approval rating briefly rose, although a recent survey put it at just 31%.

It’s possible to listen to citizens’ concerns and respect democratic processes at the same time. That is easier where there is already a solid democratic tradition. But democratic consolidation in Latin America is in peril. A look at the past year paints a somber picture. Nicaragua’s president, Daniel Ortega, has virtually eliminated any opposition to his government by deporting political opponents and stripping them of citizenship. Ecuador, a historically peaceful country, is now consumed by violence related to drug trafficking, with the shocking murder of presidential candidate Fernando Villavicencio serving as evidence that the drug trade is interfering with elections.

Peru’s deeply unpopular president, Dina Boluarte, is holding on to power despite repeated protests demanding her resignation. In Guatemala, the political establishment tried its hardest to interfere in the recent presidential election and seems likely to continue to harass President-elect Bernardo Arévalo and his party.

Millennials in Latin America face a massive challenge. Young people seem more lured than ever by populist politicians who rail against “the system”—libertarian Javier Milei’s performance in the Argentine primaries in August is a clear example. Other politicians are taking note. Lima’s mayor and former presidential candidates in Ecuador and Colombia have all expressed admiration for the Salvadoran leader.

Meanwhile, the region’s GDP forecast for this year is a meager 1.7%, according to ECLAC. Satisfaction with democracy was always going to be difficult to sustain under such conditions, so it’s no wonder that millennials are turning increasingly toward efficiency over principles.

The political scientist Samuel Huntington, in a seminal 1991 paper, identified a series of factors that predicted a “reverse wave” that would drag democracies back toward authoritarianism. He pointed to the weakness of democratic values, economic set- backs, polarization, the exclusion of the lower class from political power and a breakdown in law and order. All of these exist in Latin America today—a fact that makes Nayib Bukele seem like a harbinger of Latin America’s future.