This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on the reasons for cautious optimism in Latin America | Leer en español | Ler em português

Listen to this story read by the author by clicking the play button above.

This piece was updated on November 27.

If there’s a symbol of the current, cautiously hopeful, things-are-looking-up-but-let’s-not-get-carried-away moment in Latin America, it’s probably the Néstor Kirchner Pipeline in Argentina.

The $2.7 billion, 335-mile pipeline was inaugurated to great fanfare in July, connecting the Vaca Muerta gas field to the central part of the country. In one fell swoop, it ended Argentina’s colossal dependence on imported gas, saving the crisis-hit economy an estimated $4 billion a year in dollar reserves.

Like so much else in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) today, the reality could be much better. The pipeline for now only allows Argentina to supply more gas at home; further extensions will be necessary before it can export to neighbors like Brazil and Bolivia, much less serve the energy-hungry European market amid the war in Ukraine. While Vaca Muerta is the world’s second-largest shale gas reserve, and companies including Shell, YPF and Exxon have made big bets there, the field only produces perhaps a third of its potential due to Argentina’s capital controls, insufficient infrastructure and political instability.

But still, it’s a clear step forward.

Despite the bad politics.

Despite the pessimism of recent years.

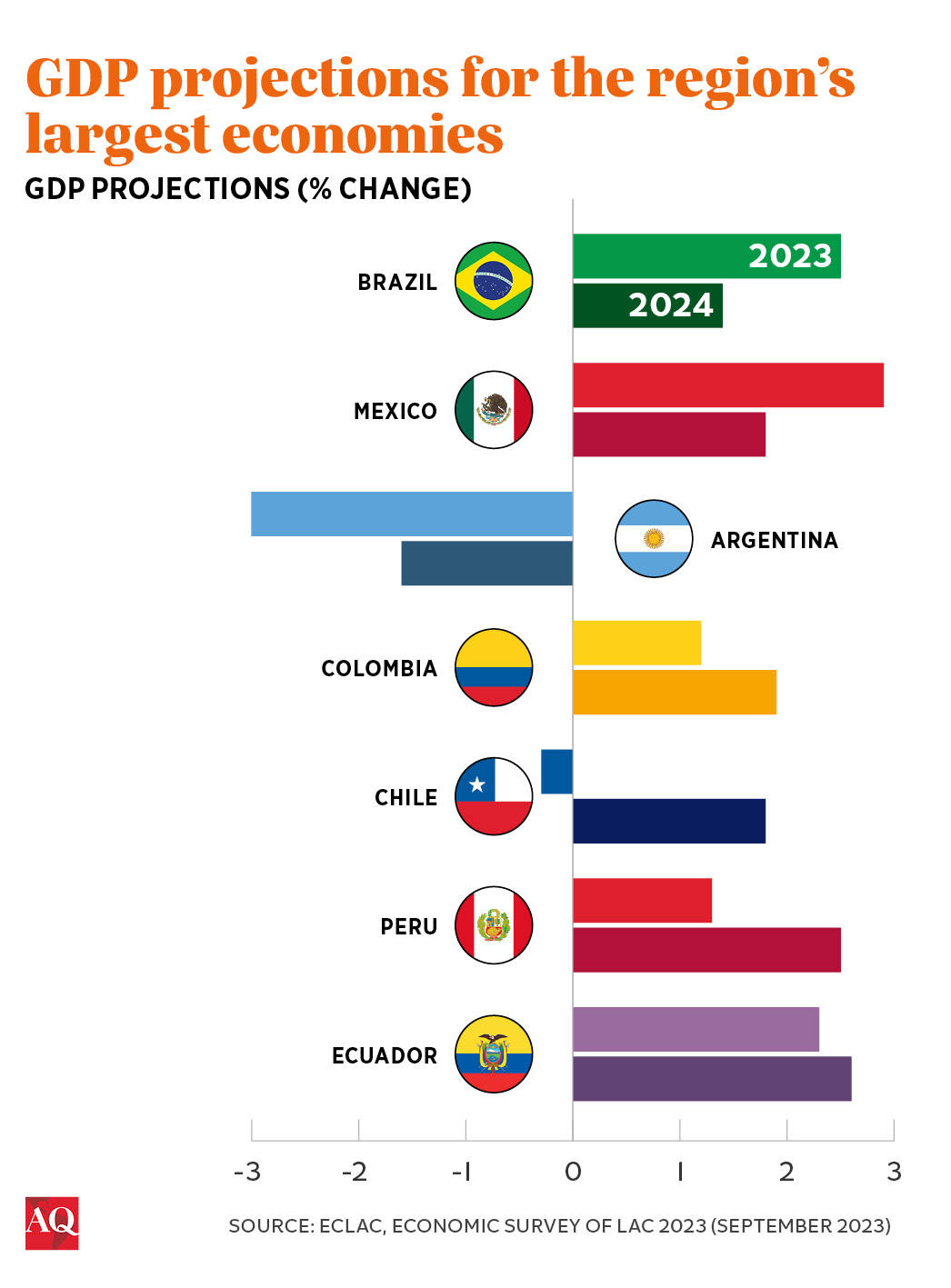

Indeed, after a “lost decade” that saw economies stagnate across Latin America and the Caribbean, a new optimism appears to be taking hold in some areas. It’s uneven, concentrated in certain countries (especially Brazil and Mexico) and sectors (energy, agribusiness and “nearshoring,” among others). But the bottom line still looks like a modest increase in growth, and a chance at better times for investors and many of LAC’s 660 million citizens.

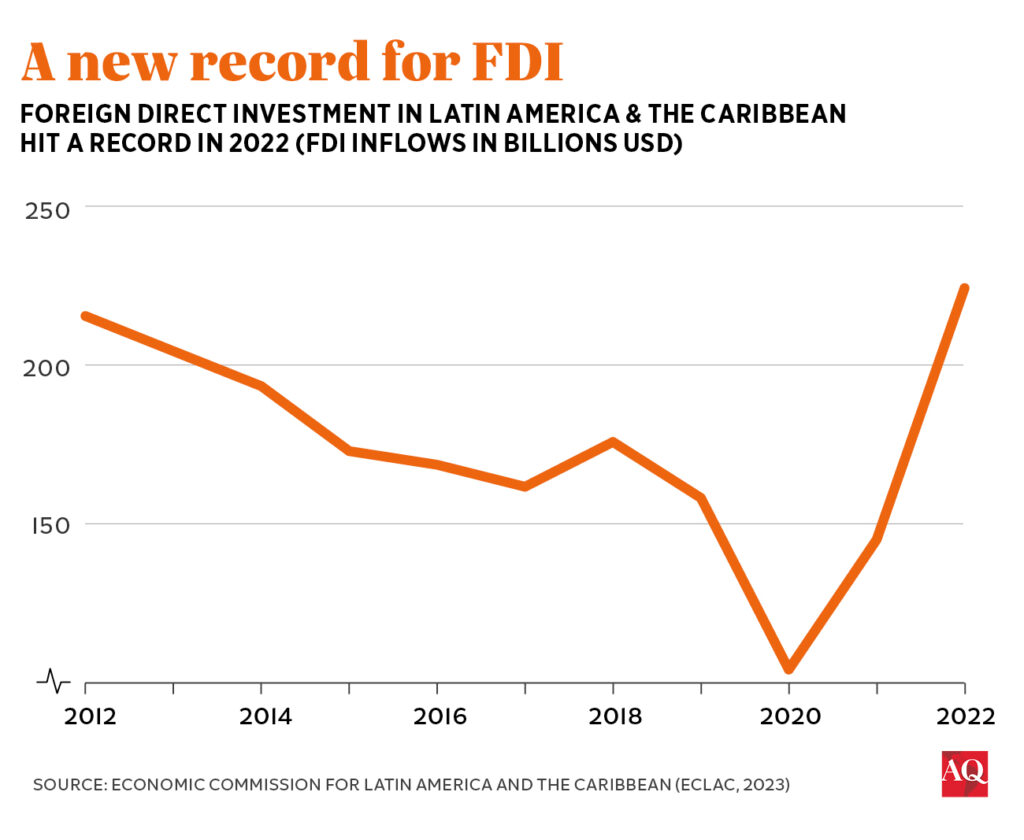

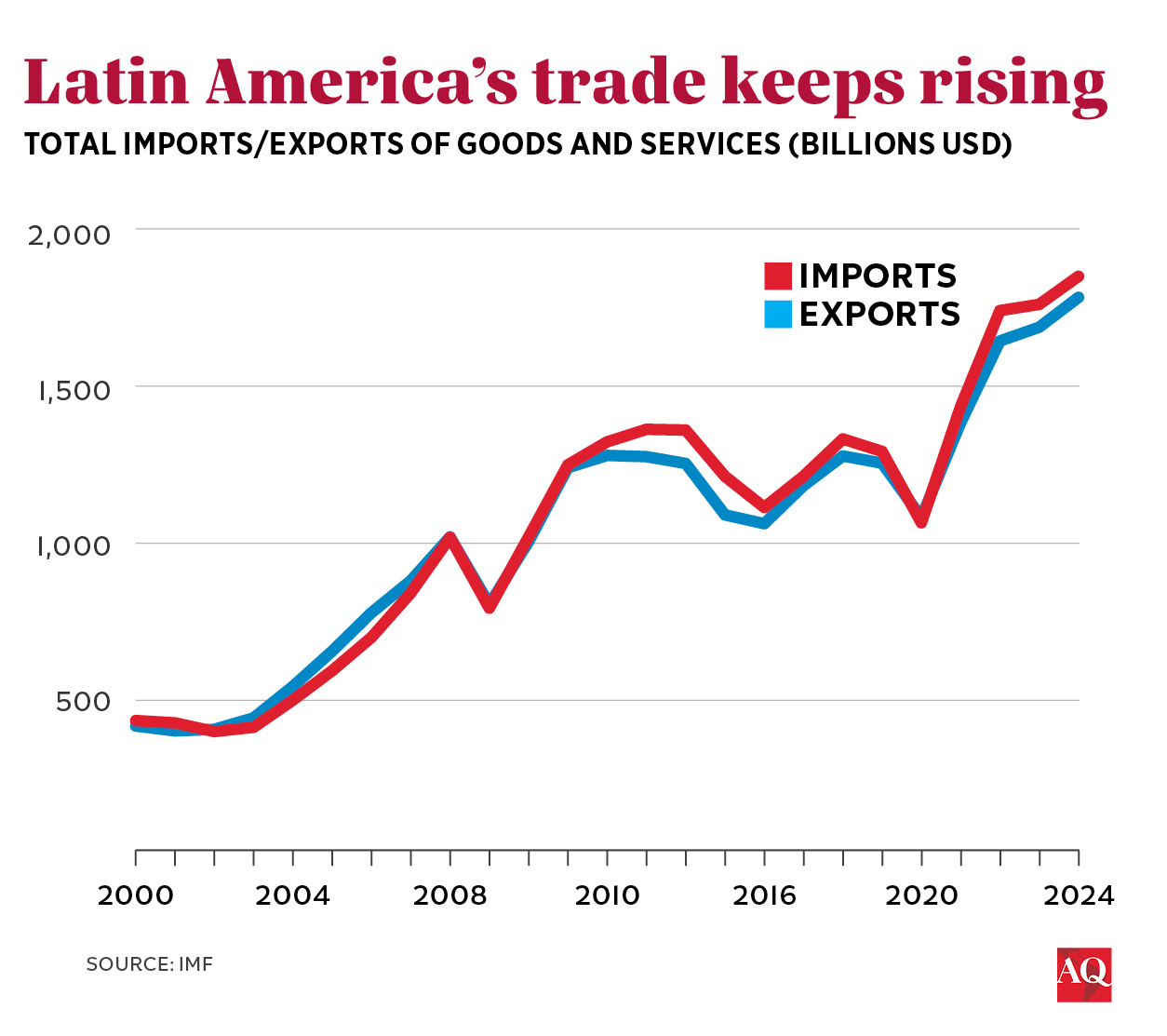

Skeptical? Frankly, everyone is. But many are making bets anyway. Foreign direct investment in LAC soared 55% in 2022 to $224 billion, its highest value on record, during a year when FDI flows globally shrank 12%. This year, the world’s top performing emerging market currencies have been Colombia, Mexico and Brazil, with Peru not far behind, as global capital flows in. Mexico passed China in July to become the United States’ top trading partner for the first time in 20 years. Underlying all this is the idea that, at a time of rapidly shifting global trade and capital flows, Latin America has much of what the world needs: Strategic commodities, renewable energy sources, skilled workers close to the U.S. market, and more.

“I’m seeing not just optimism, but action,” Ilan Goldfajn, the president of the Inter-American Development Bank, told me. “People realize there are global challenges that Latin America is uniquely positioned to be part of the solution for.”

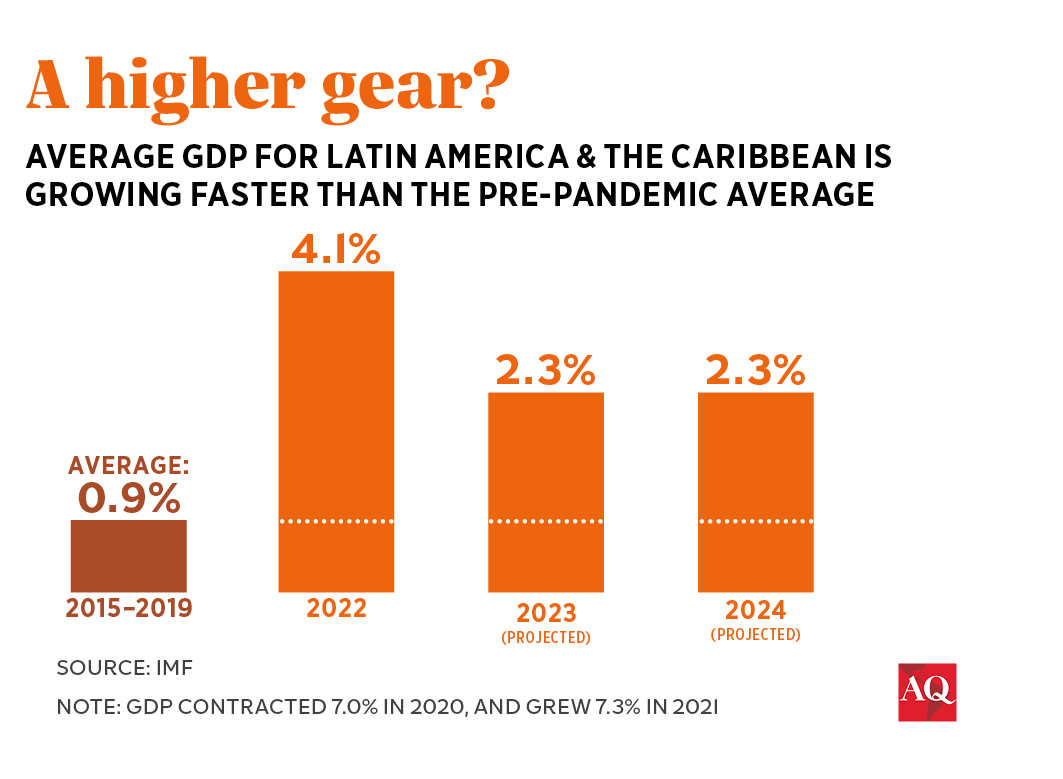

No one is “throwing butter at the ceiling,” to use an old Argentine expression for boom times. The region’s growth rates remain below their potential, trailing other emerging markets in Africa and East Asia. But 2023 will be the third year in a row that the International Monetary Fund and others were forced to raise their LAC growth forecasts after they proved too bearish. The pessimism that enshrouded the region in the wake of COVID-19 appears to have been exaggerated. The 2.3% GDP growth expected for 2023 and 2024 would be more than double LAC’s average in the five years prior to the pandemic.

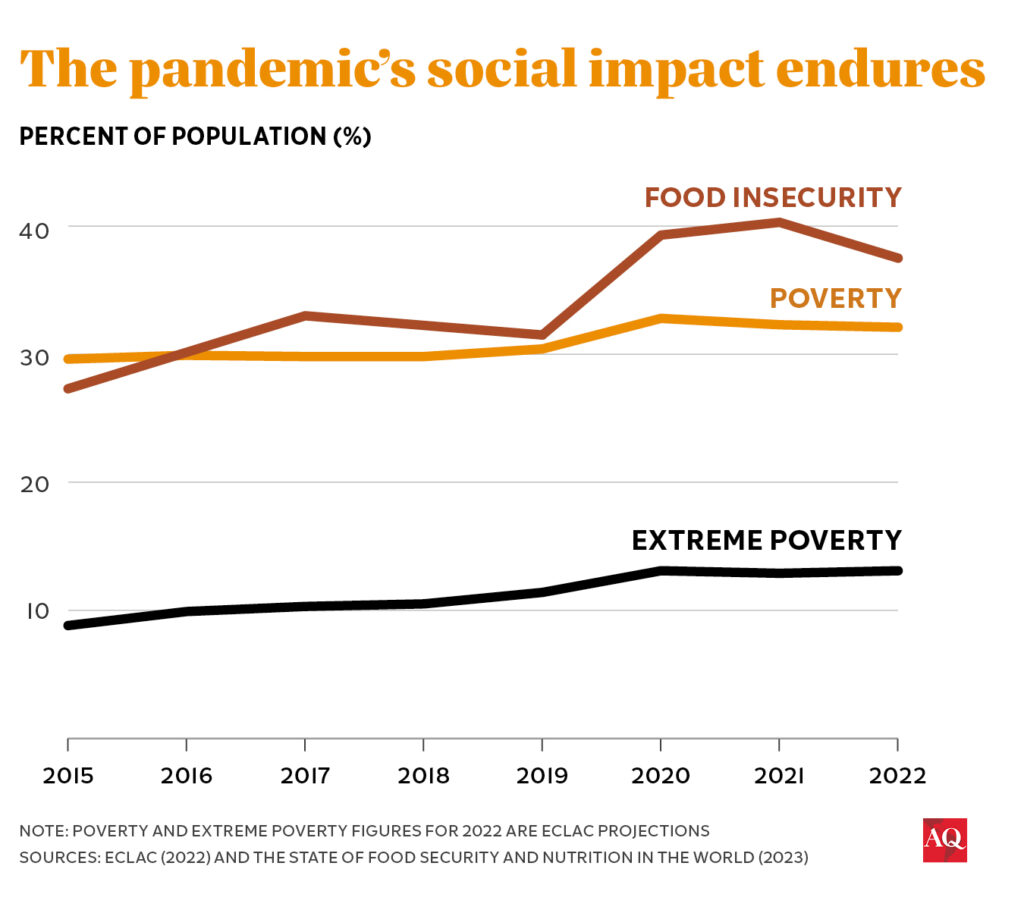

Populism and other -isms could still suffocate the recovery. Much of the rosier scenario depends on the global economy, and the health of both the United States and China are big question marks. Wars in Ukraine and the Middle East could veer out of control and destabilize the entire world. The incomplete Argentine pipeline highlights how critical further infrastructure expansion will be going forward. Enduring high levels of poverty and hunger, a legacy of the lost decade, means it could still take years for everyday people to feel a meaningful improvement in their lives.

Nonetheless, there is still a relatively bullish case to be made for Latin America and the Caribbean in the years ahead. In this article, I will focus on five main reasons for optimism, based on interviews with business leaders, politicians, analysts and everyday people who were brave enough to express at least some hope.

1 |

Latin America is far

A few years ago, in a conversation with former Brazilian President Fernando Henrique Cardoso about the growing U.S.-China rivalry, Cardoso told me: “I think we have to take advantage of our greatest strategic asset: Brazil is far.”

He explained with a wry smile that in a volatile new era of great power competition, Brazil’s sheer geographic distance from hot spots like Ukraine, Israel/Gaza or Taiwan was an underappreciated advantage. If his country and others in Latin America could maintain a certain neutrality, they would be considered a safe haven for everyone to invest, even in a fragmenting world. Perhaps, Cardoso said, they could even benefit from a kind of bidding war as Washington, Beijing and other powers competed for influence and natural resources.

That’s exactly what seems to be happening in LAC in 2023. The morality and long-term strategic wisdom of neutrality, or “non-alignment,” are debatable. But for now, in the lobbies of business hotels in São Paulo, Santiago, Panama City and Bogotá, you will hear an amazing variety of Chinese, English, Arabic and French as deals are being made.

In July, the European Commission announced investments worth $48 billion over five years throughout the region in areas including green hydrogen. That same month, more than 100 officials and business leaders from Saudi Arabia visited Brazil, signing 26 bilateral investment deals focused on mining and agribusiness. The Chinese are making one of their biggest strategic investments in a new $1.3 billion deepwater port north of Lima, which could reduce average shipping times to Asia from 45 to 35 days. The United States remains LAC’s biggest investor, accounting for almost 40% of FDI.

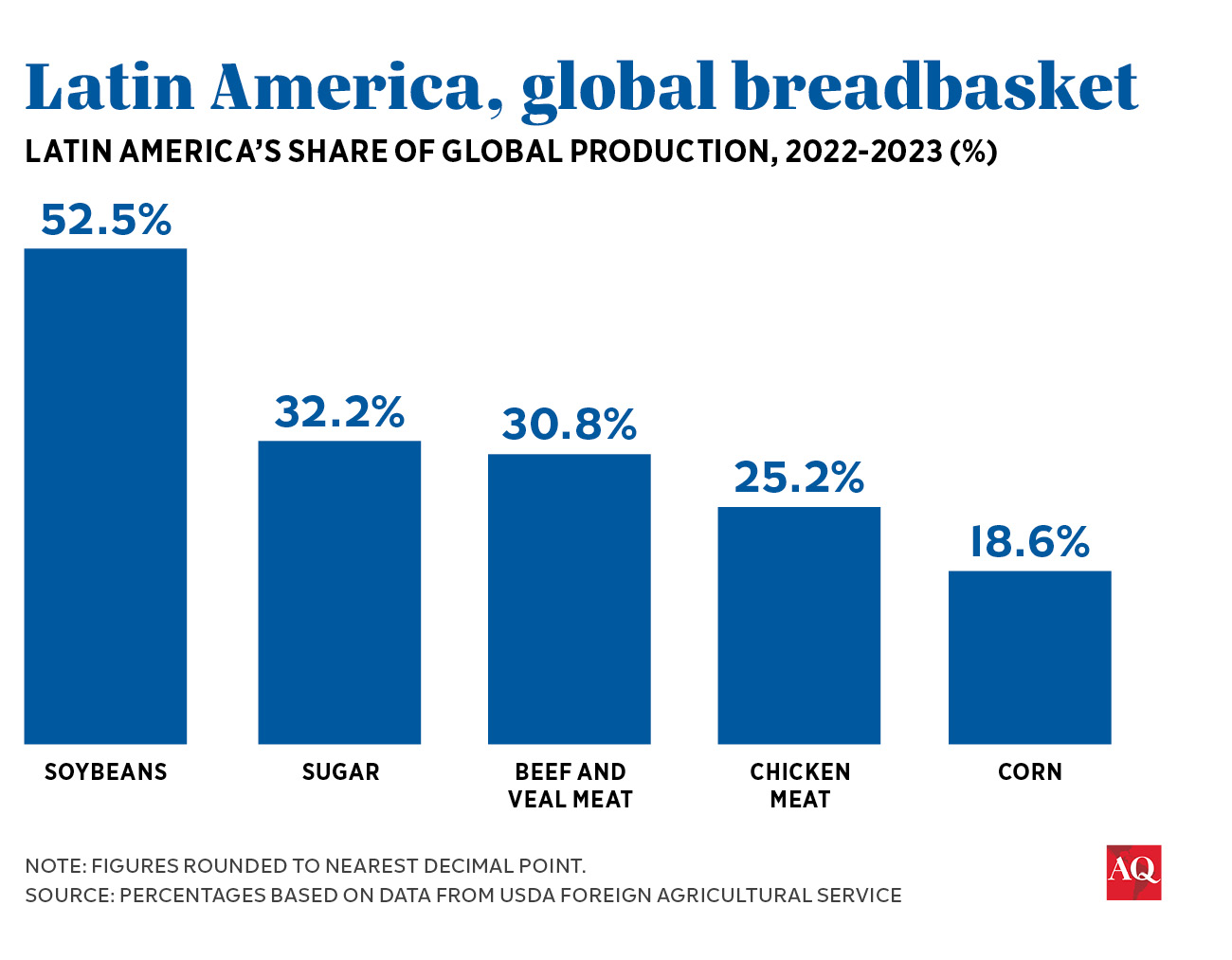

The common thread in many deals is agribusiness—Latin America is the world’s largest net exporter of food, critical as the world’s middle class is projected to double over the next three decades, to 3 billion people. Brazil has been the main beneficiary so far, but Argentina is poised to join in if, as expected, 2024 brings better weather (after its worst drought in 40 years) and better politics (following this October’s elections).

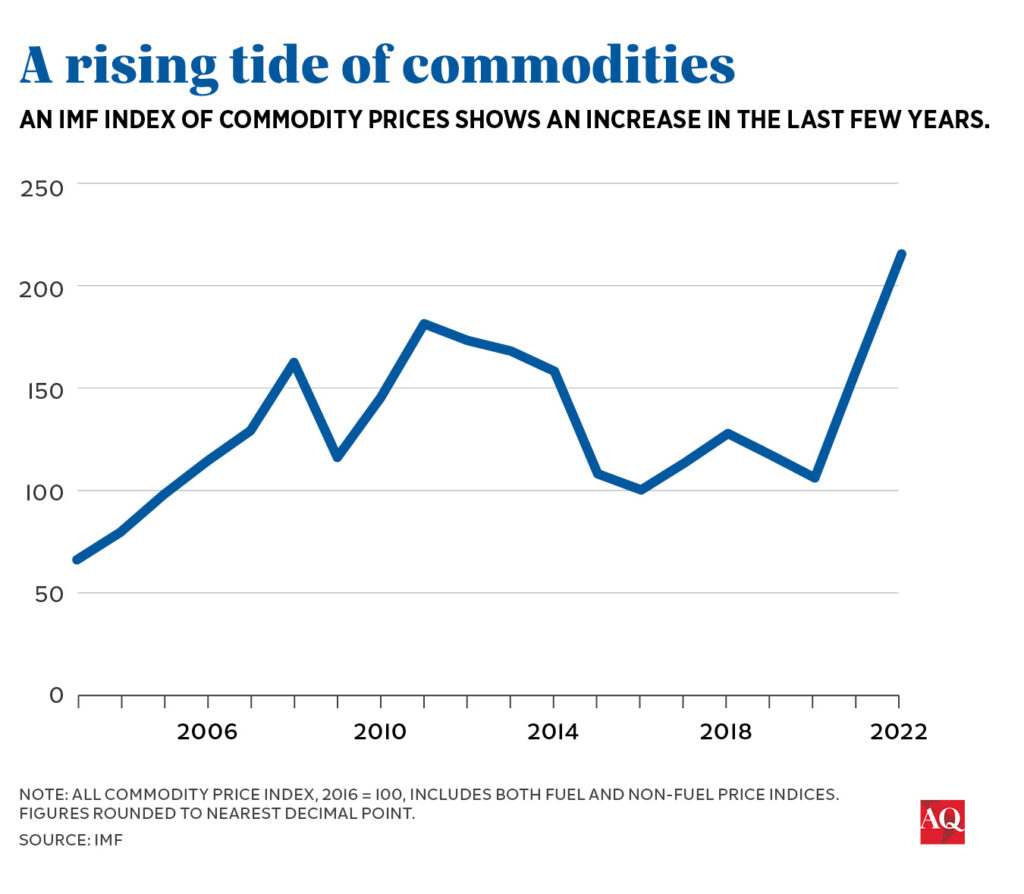

Unlike the commodities boom of the 2000s, this cycle is “not mainly a price boom. It’s more of an investment boom” that could increase yields and efficiency, Goldfajn told me. As such, it won’t be as dramatic—but it may prove more sustainable.

2 |

Latin America is near

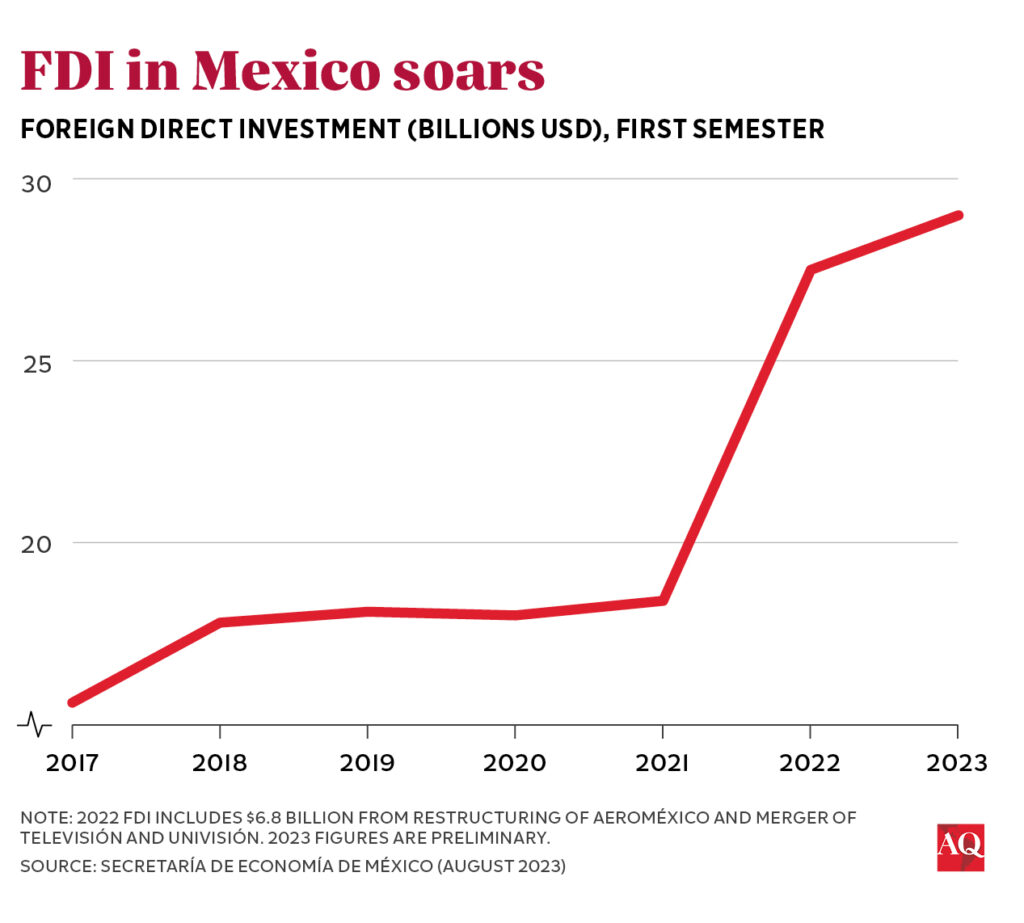

At the same time, many countries are taking greater advantage of their proximity to the United States, as companies bring manufacturing closer to home following the pandemic and rising tensions with China. The trend of “nearshoring” has been more lucrative than some predicted—mainly (but not exclusively) in Mexico, where FDI is up 40% this year, helping the economy grow at a 3% pace after years of stagnation.

The politics around nearshoring could be a lot better. Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s government has a difficult relationship with business, and 2024 could see the return of Donald Trump, who routinely threatened Mexico with border closures during his first presidency. Inconsistent supplies of electricity and water, infrastructure bottlenecks and bad security are all barriers. Real estate in manufacturing hotspots like Monterrey is so scarce that some industrial parks are requiring a 10-year commitment from tenants.

And yet, investments keep coming: Tesla in March made its first foray into Mexico, a $5 billion “gigafactory” to help it meet a goal of cutting manufacturing costs for its electric vehicles in half. (The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act allows tax credits for electric vehicles even if they are built in Mexico, due to its trade agreement.) Meanwhile, non-U.S. companies are also eager to gain a foothold in North America: Taiwanese electronics manufacturer Quanta Computer announced a $1 billion investment in Mexico in May. Throughout LAC as a whole, nearshoring has the potential to add $78 billion a year to the region’s exports, according to the IDB.

The bank said more than half the additional nearshoring potential lies outside Mexico. Intel said in August it would invest $1.2 billion in Costa Rica, after Washington agreed to include that country in U.S. efforts to boost the manufacturing of semiconductors. Other countries in the Caribbean basin like Honduras ($1 billion in potential added exports), Trinidad and Tobago ($480 million) and Jamaica ($140 million) could join in, the IDB says.

It’s a heady era. “Honestly, we never expected to see semiconductors being manufactured in Mexico, or electric cars and so on,” Marcelo Claure, the Bolivian-American former CEO of Sprint and Softbank International, who is now running an investment fund focused on Latin America, told me. “Think about how far we’ve come, and you realize what could still be ahead.”

3 |

It’s a potential energy powerhouse.

The word “potential” here is important. There has been so much hype about lithium, for example; Latin America has about 60% of the world’s identified resources. Yet production has underperformed, as governments in Chile and Bolivia, especially, have passed legislation requiring the state to take a major role in exploitation. The recent discovery of an apparently massive lithium deposit along the Nevada-Oregon border raises the question of whether by the time countries get the policy mix right, the world will have moved on.

LAC attracted only $20 billion in renewable energy investment in 2022, representing just 4% of the world’s total. That means the region is punching at only about half its weight in the global economy, despite the clear potential for sun, wind and hydro power. “Taking advantage of these will require greater integration into the global economy. Yet, paradoxically, in the face of these opportunities, LAC is becoming less integrated,” said a recent study led by the World Bank’s chief economist, William Maloney.

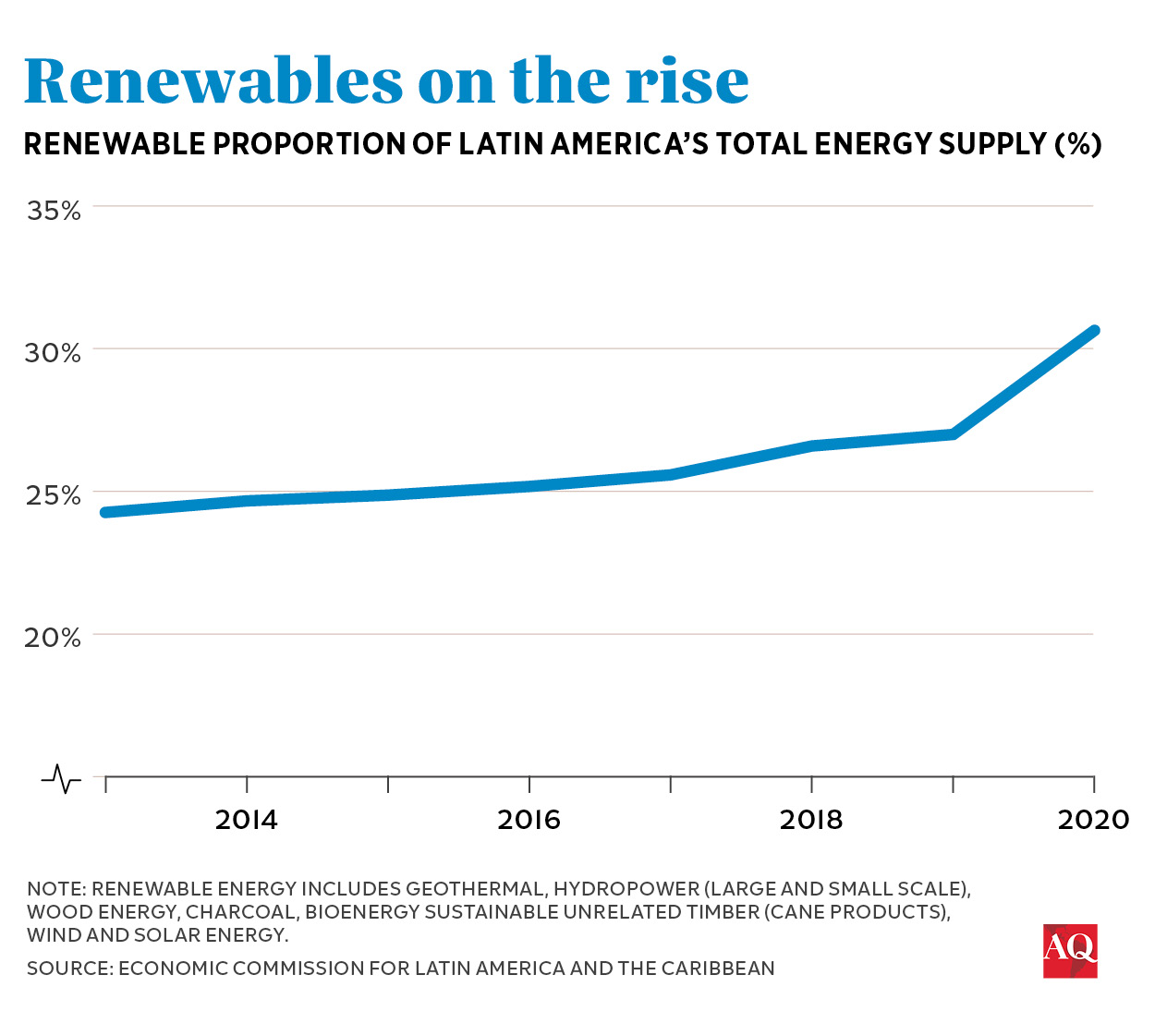

Some counsel patience, arguing the region’s abundant resources, and the needs of the global energy transition, will eventually win the day. More than a quarter of LAC’s primary energy already comes from renewables—a level twice the global average. Brazil’s wind power industry has doubled its capacity since 2018, potentially putting the country in line to be the world’s fourth-biggest producer by 2027 behind China, the U.S. and Germany, according to a local industry body. Uruguay in June announced $4 billion in new renewable energy projects, half of which focused on green hydrogen—an area where Chile and others also have vast potential.

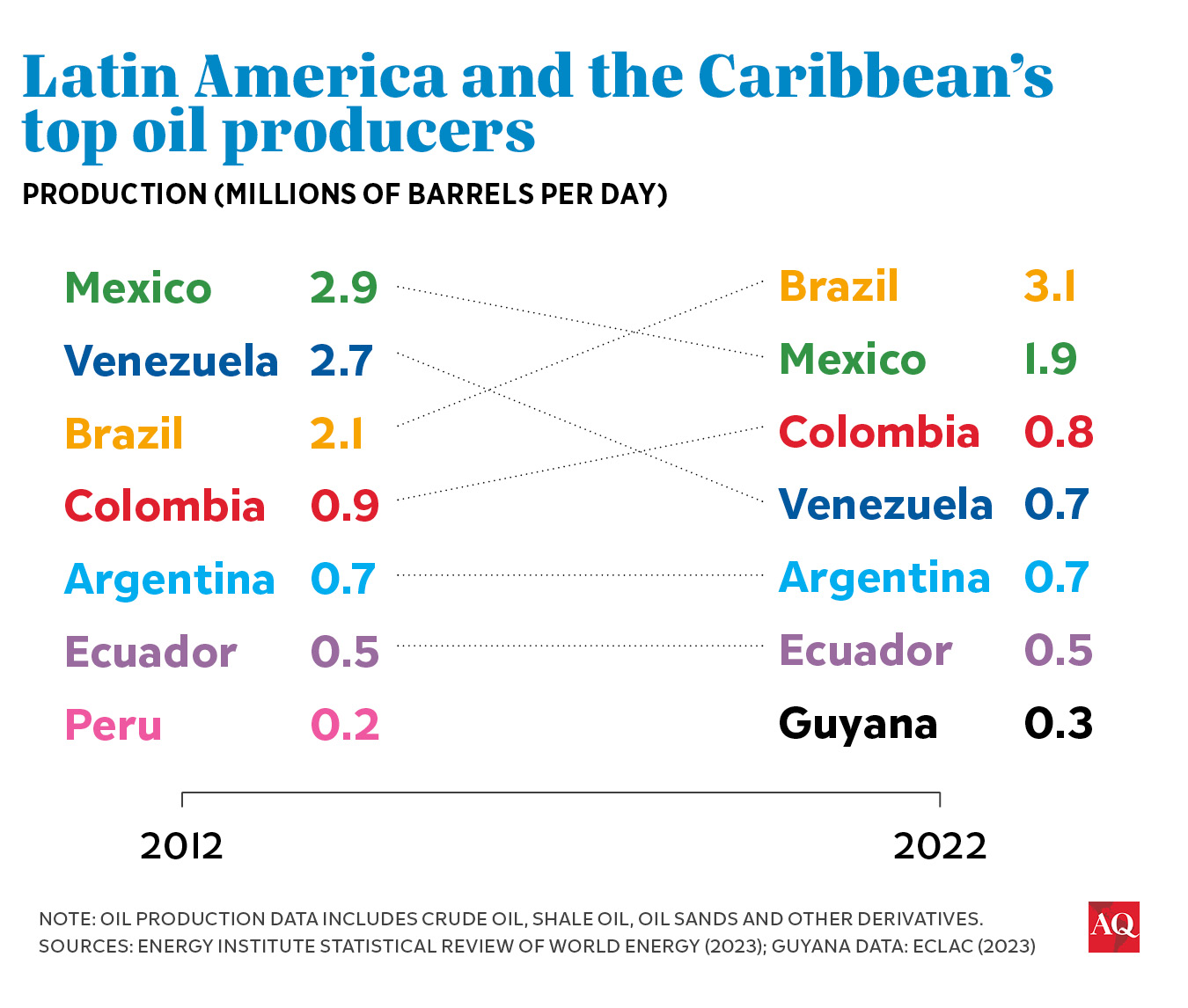

Latin America’s old-fashioned oil and gas sector also still offers some opportunities. The region’s overall oil output has fallen 20% in the last decade to 7.8 million barrels per day, mainly due to declining production in Mexico and Venezuela. But ascendant players Brazil and Guyana may together account for half of LAC’s oil output by the end of this decade, according to a Columbia University study.

There is vast potential elsewhere, although the backlash against oil, and extractivist activities more broadly, was on display in August when 59% of Ecuadorians voted to end oil production in a national park in the Amazon, turning their backs on as much as $13 billion in projected revenue over the next 20 years. Voters in the Argentine province of Neuquén are increasingly upset by rising crime, housing shortages and inequality associated with development of the nearby Vaca Muerta field, local professor and political analyst Maria Esperanza Casullo recently said on the Americas Quarterly Podcast.

4 |

The politics aren’t as bad as you think.

I asked Claure, the veteran CEO of global companies, if politics were at risk of sabotaging Latin America’s more promising moment.

“What about politics in the U.S.? Or Europe?” Claure retorted. “I’m not sure they’re any worse in Latin America, to be honest.”

That’s not exactly a ringing endorsement, but he has a point. In this era of polarization and social media, we risk becoming so obsessed with day-to-day dysfunction that we miss the moments when officials actually deliver. For example, Latin America’s central banks understood, arguably faster than in any region in the world, that the inflation of the pandemic era was not “transitory”—and interest rate hikes were needed. As a result, inflation is slowing almost everywhere but Argentina—and banks in Brazil, Chile and Uruguay are cutting rates, even as they continue to rise in parts of the developed world.

There is no doubt that populist policies around the region continue to suppress economic growth. But today’s “new pink tide” of leftist presidents such as Colombia’s Gustavo Petro, Chile’s Gabriel Boric, Mexico’s Andrés Manuel López Obrador and Brazil’s Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva have mostly defied doomsday predictions by keeping a steady hand on fiscal management. Voters’ fears of “becoming the next Venezuela” are often exaggerated—but in practice, the specter of repeating that tragedy has probably limited the ambitions of an entire generation of leftist leaders in Latin America.

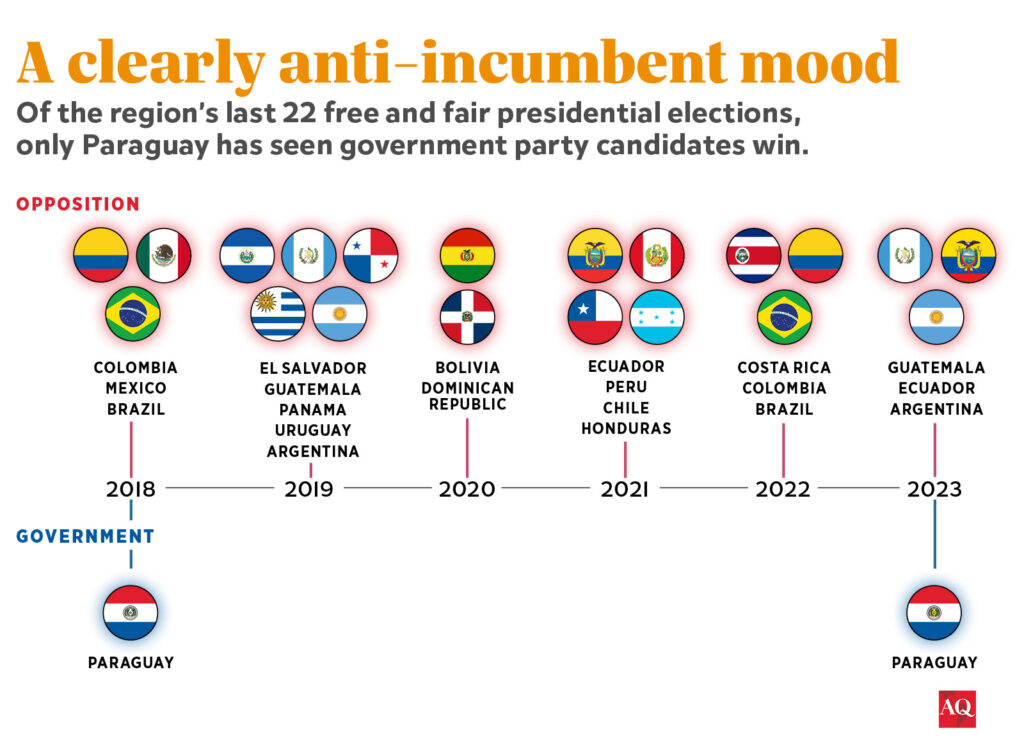

For better and for worse, this is also an era when it’s difficult for any one politician to gain too much power. Of the last 22 free and fair presidential elections in Latin America, an opposition party has won in 20 of them. This is partly a result of dysfunction; poverty, unemployment and food insecurity were all rising in the region even before the pandemic hit. In such an environment, leaders have usually failed to meet expectations and lost popularity soon after taking office, opening the door to a different kind of leader—often an “outsider.”

In that environment, democratic erosion remains a real concern. But when presidents try to stay in power by interfering in elections, persecuting their opponents or illegally grabbing power for themselves, as happened in Brazil, Guatemala and Peru in the past year, institutions have held their ground. “The single most exciting thing in Latin America right now is the strength of democracies,” said Susan Segal, CEO of the Americas Society and Council of the Americas, the organizations that publish AQ. “It’s a surprise to everybody, and contrary to the way things used to work in the region.”

5 |

The digital story really is fantastic.

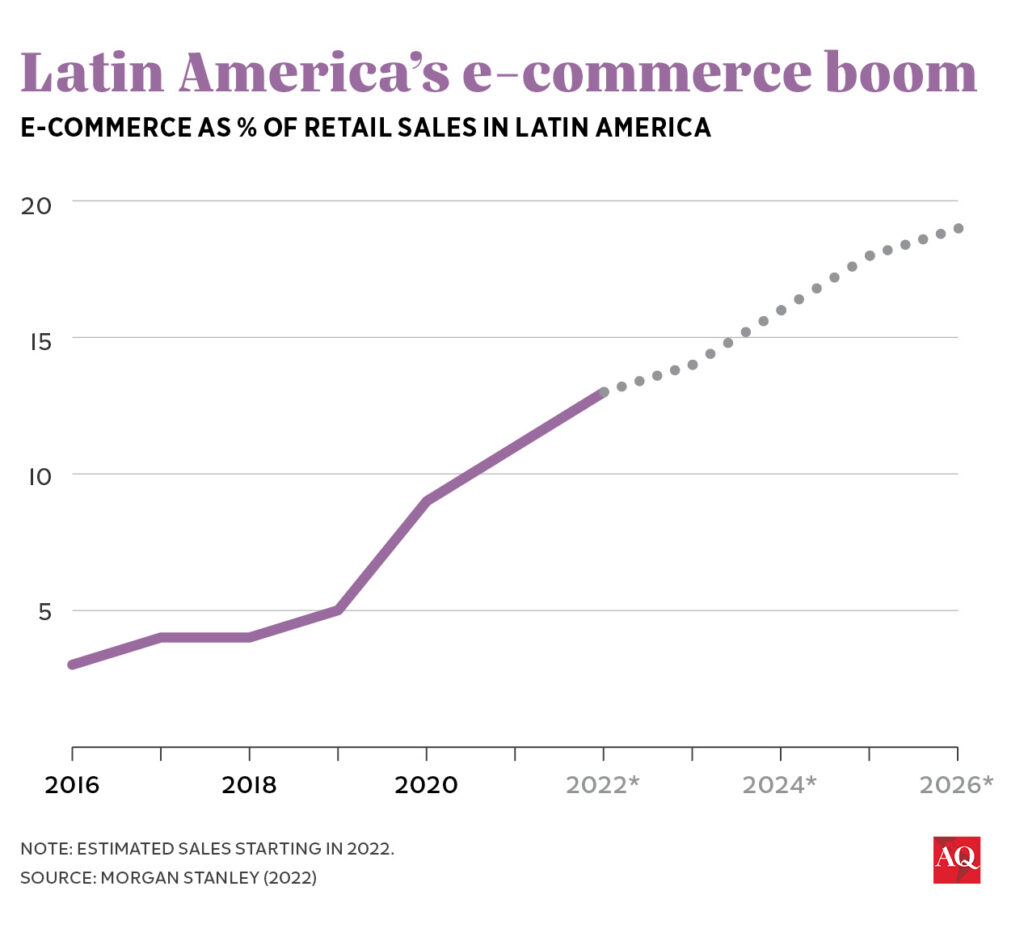

The pandemic was indisputably awful in Latin America and the Caribbean, which accounted for perhaps a third of deaths globally despite having just 8% of the world’s population. But it did accelerate the transition to a more digital economy, as the region’s relatively young population, which has some of the world’s most intense rates of smartphone use, embraced e-commerce, fintech and other segments.

The expansion’s speed has been stunning. Mercado Libre, the region’s largest e-commerce company, said in April it will hire an additional 13,000 people, bringing its total headcount to 53,000—up from just 10,000 at the end of 2019. More than 80% of the company’s new hires will be in Brazil and Mexico. Overall, e-commerce is expected to account for almost a fifth of retail purchases in LAC by 2026, according to a Morgan Stanley study.

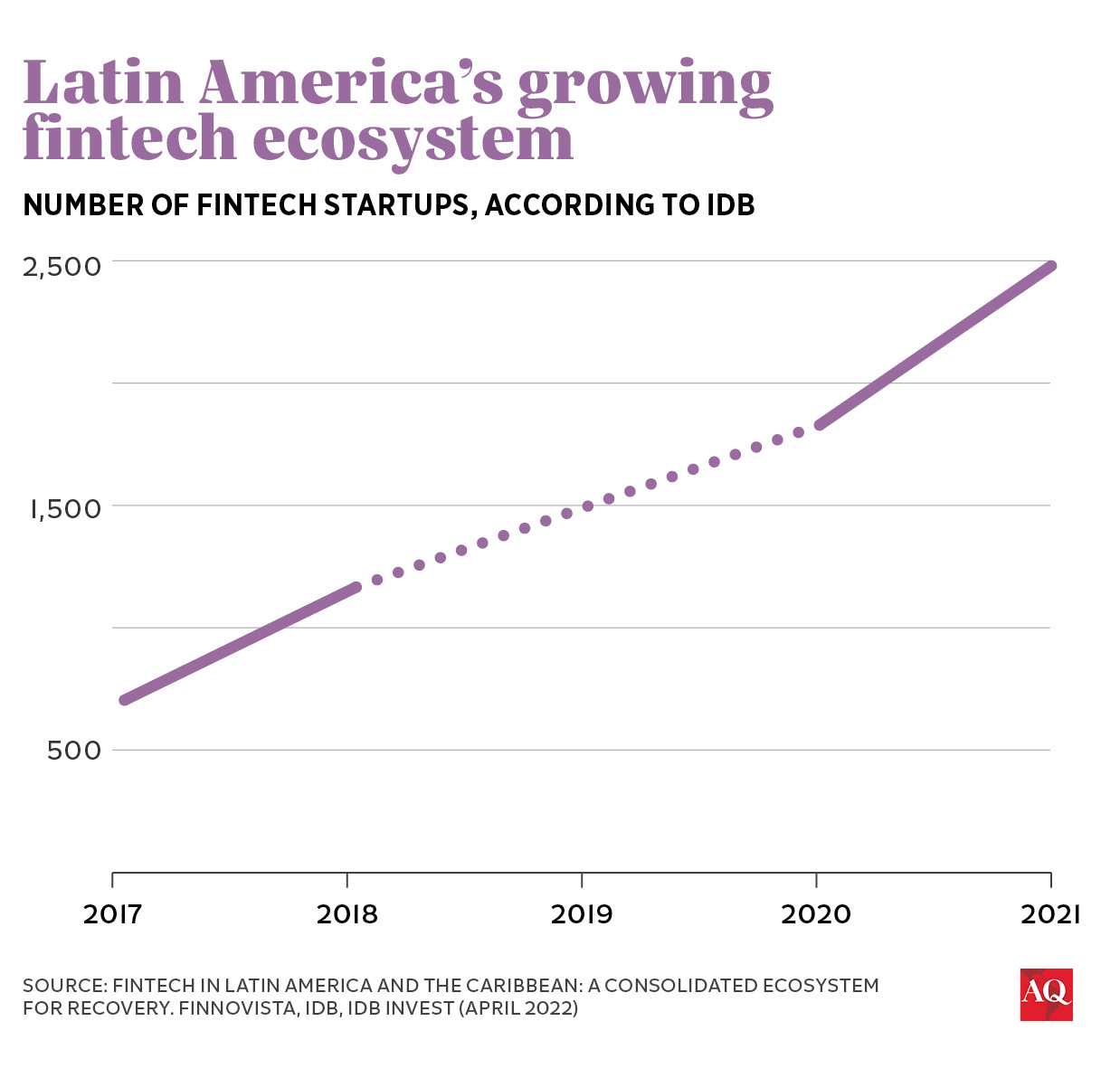

New technologies are allowing Latin America’s working classes, many of whom work in the informal sector and have never had a bank account, to access credit for the first time. According to the IMF, the value of transactions at fully online digital banks or “fintechs” mushroomed to $123 billion in 2021, up from just $17 billion four years previously. The value of digital payments has also doubled in that time, to $215 billion, often using innovative new platforms such as Mexico’s CoDi, Costa Rica’s SINPE Móvil or Brazil’s Pix.

Nubank, the region’s fintech leader, now has more than 85 million customers—enough to put it among Latin America’s largest financial firms, Bloomberg reported in August. Yet David Vélez, the company’s Colombian-born CEO and founder, told me: “It’s still very early days for fintech,” noting that traditional banks still own more than 85% of “every single vertical,” including insurance and credit to small businesses.

Looking forward, Vélez said artificial intelligence “is going to be a horizontal technology that could genuinely revolutionize access to education and healthcare.” Some of that innovation will likely come from Latin American tech firms, which have traditionally punched above their weight. “We’re really now seeing the second or third generation of tech entrepreneurs in Latin America,” Segal said. “They’ve created this network community where the successful leaders are funding and mentoring a lot of the younger people.”

Final thoughts

“It’s always easy and safer to be negative about Latin America,” the longtime regional editor of The Economist, Michael Reid, once told me. To the drab record of the last decade, one can add several other caveats: Climate change and El Niño will continue to play havoc with the region’s economies. The seemingly never-ending spread of organized crime, fueled by demand for drugs from the United States and Europe, is now wreaking havoc—and destabilizing politics—in countries that previously saw little trouble, like Chile and Ecuador. Life is still difficult enough for ordinary people that record numbers of migrants from LAC are pouring across the U.S. border. Corruption, inequality and political mismanagement may prevent gains from improving the lives of the working classes.

But the bottom line is basically this: The external context for LAC right now is so favorable, on a variety of fronts, that it is overcoming other headwinds. If the policy mix was better, the region might be growing 4% or 5% a year. But 2% or perhaps a little better still feels like progress. That growth, plus the investments being made, might be enough to create a little more well-being among the region’s citizens—which could in turn help the politics get better.

It sounds, in other words, like the beginnings of a virtuous circle—not an overwhelmingly positive one, but better than the status quo. “Overall, I’m bullish,” Claure said. He’s not alone.

José Enrique Arrioja and Emilie Sweigart also contributed to this story.

This piece was updated to include information about presidential elections in Ecuador and Argentina.