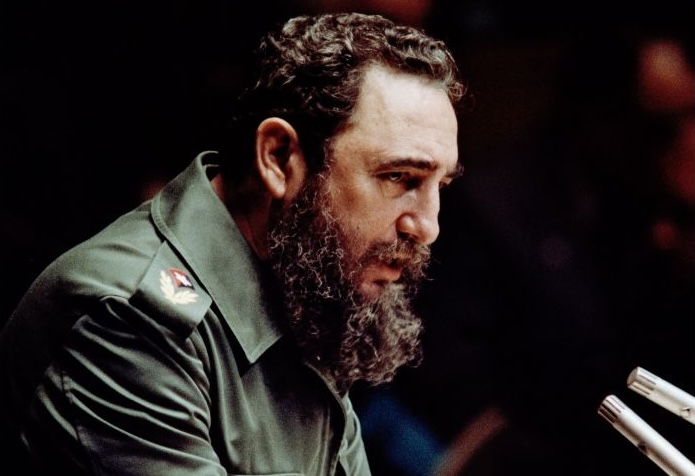

On January 8, 1959, a 32-year-old Fidel Castro and his “Caravan of Freedom” triumphantly entered Havana in open-top Jeeps to a crowd so large and delirious that “it was impossible to differentiate the procession from the audience,” remembered an American photojournalist who lost a shoe—and, more disastrously, his camera—in the ensuing melee. “We have defeated tyranny,” Castro told the masses that day. “Now we must defeat lies, intrigue and ambition … This time, the revolution will truly take power.” He was right. Over the next half-century, Castro and his allies would wield tremendous power not just at home but abroad—producing similar regimes in Venezuela and Nicaragua, and influencing generations of other leftist leaders throughout Latin America.

Fidel Castro died in 2016. But it is worth asking whether 2026 will be the year when the Fidel Castro Era finally ends. Even prior to the U.S. invasion on Saturday that delivered Nicolás Maduro to a New York jail cell, the political and economic model pioneered by Castro showed signs of being in its death throes. To be sure, there will always be a place for a comparatively moderate left focused on social justice and redistribution in a region with the world’s biggest gap between rich and poor. But the repressive, confiscatory, aggressively anti-capitalist brand of leftism practiced by Cuba and Venezuela has never been so unpopular throughout Latin America—not primarily because of Donald Trump’s actions, but because its own failures have never been so publicly visible.

If that all sounds like a Miami-style fever dream, well, fair enough. Observers have been predicting the imminent demise of the Castros and their ideals since at least the Bay of Pigs. It’s also true that the chavistas are still in charge in Venezuela, at least for now, in the wake of Maduro’s arrest and rendition. The most heavy-handed U.S. intervention in Latin America since the invasion of Panama in 1989 could still go horribly awry; even if it succeeds, it may still create a 21st century version of the anti-imperialist backlash that helped give rise to Castro in the first place.

But prior to his departure, Maduro did more to damage castrochavismo than any of the CIA’s infamous exploding cigars ever could. The well-chronicled economic collapse of Venezuela shaved 75% off the once-prosperous country’s GDP and generated an exodus of more than 8 million people over the past decade, the vast majority of whom emigrated elsewhere in South America. That allowed people throughout the continent to see the model’s failures firsthand—Venezuelan lawyers and doctors who became Uber drivers and Rappi deliverymen, or fell even further. I will personally never forget walking the streets of Bogotá in 2019 and coming across a man on his knees, rocking back and forth with his hands clasped as he repeated “Soy venezolano, soy venezolano,” as if that was enough to explain his state.

Virtually every Chilean, Peruvian, Colombian or Brazilian has had similar experiences over the past 10 years—and also felt the strains on their own countries that mass emigration can cause. And while it’s true that U.S. sanctions contributed to Venezuela’s collapse, there is little doubt about who Latin Americans blame most. The latest regional poll by Latinobarómetro, surveying more than 19,000 people across 17 countries, showed Maduro was by far the most unpopular figure in the region, truly in a category of his own.

Cuba’s recent struggles, while less visible in the rest of the region, have only reinforced the cautionary tale, even for generations accustomed to hearing about economic crisis since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Daily blackouts, food shortages and the exodus of up to a fifth of the Cuban population since 2020 have raised questions about how much longer Castro’s successor, Miguel Díaz-Canel, can endure especially now that Maduro is gone. The other remaining true believer, Daniel Ortega of Nicaragua, has fared no better.

While there are still leftist leaders in Latin America who sympathize with Maduro, and may retain romantic notions of Castro himself, none remain willing to emulate them. Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, even in his most radical period of the 1990s, cited as his role model not Cuba’s leader but Henry Ford—a model of capitalism in which workers are paid enough to be able to afford their company’s product. Claudia Sheinbaum may have some socialist ideas, but she has fought tooth and nail to maintain Mexico’s free trade deal with the United States and met with countless business leaders, foreign and domestic, in an effort to solicit private investment. Gabriel Boric, who will leave Chile’s presidency in March at age 40, has consistently condemned Maduro’s abuses, suggesting that a younger generation of Latin American leftists may be distancing themselves from the Cuba-Venezuela model entirely.

With several Latin America countries already having shifted right, and even more change expected in elections this year, it is indeed possible to wonder if an era is ending. It remains to be seen whether Trump and his secretary of state, Marco Rubio, will be willing and able to completely sweep aside the remnants of Maduro’s dictatorship over the next year. Cuba’s regime may—once again—find a way to somehow survive, even as it loses its benefactor of recent years in Caracas. A different brand of destructive economic ideas may yet emerge under a new, charismatic leader in a place like Bogotá or Buenos Aires. But it still feels like the particular chapter of history that began that day at Camp Columbia in Havana, in a din of church bells, horns and cannon fire, may be coming to a close before our very eyes.