As Peru’s unrest approaches the two-month mark—with increasing violence, police repression and instances of vandalism—some observers see a connection to the wide-scale protests that ushered in political change in other Latin American countries in recent years. An article in The Economist has pointed to the apparent similarities with events in Colombia in 2021, Chile’s estallido social in 2019, and Ecuador’s Indigenous mobilization against former President Lenín Moreno the same year.

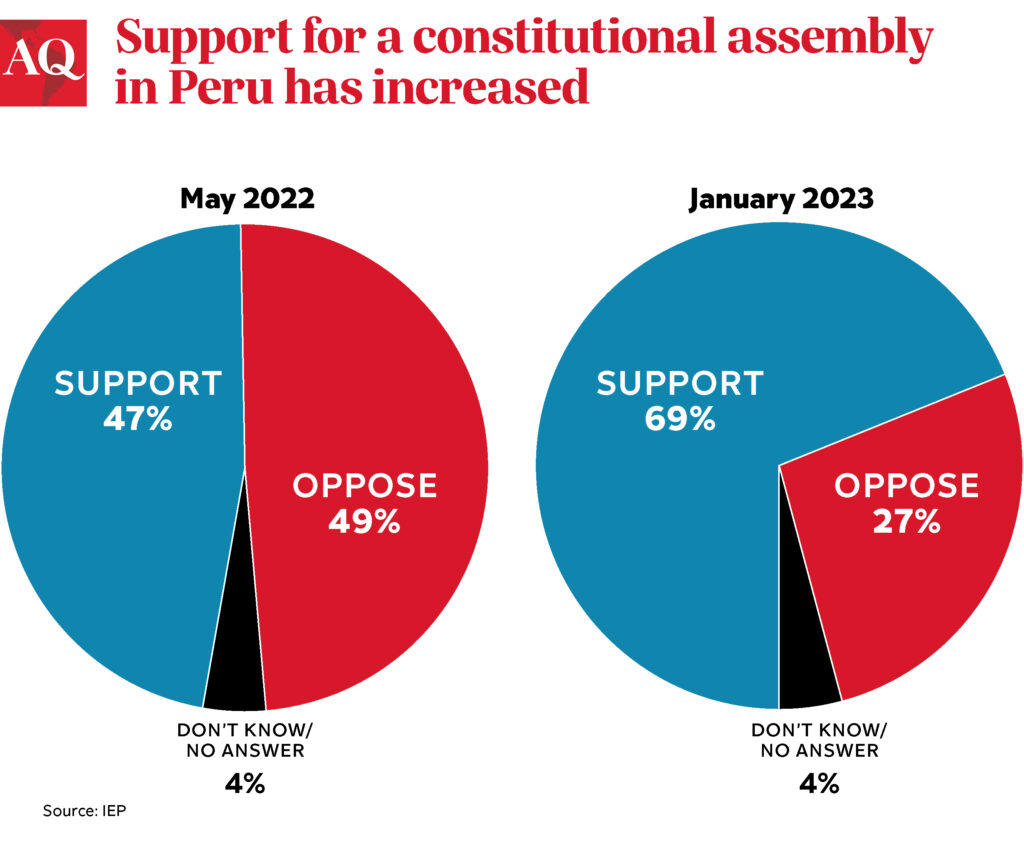

Indeed, there is the hope circulating within left-leaning sectors—accompanied by a recent announcement by President Dina Boluarte raising the prospect of constitutional reform—that the country is undergoing a “constitutional moment,” meaning that the current turmoil could lead to a new constitution, a long-desired goal. Recent polling seems to uphold this idea. According to pollster IEP, 40% now want a new constitution, compared with 23% in July 2021. 69% would approve the implementation of a constitutional assembly, up from 47% in May of last year. Support for a constitutional assembly is highest in the country’s southern regions, where most of the more aggressive protesting has occurred so far, at 81%. Leftist parties are trying to capitalize on this sentiment, presenting a series of bills to allow for this mechanism, and have stated that they will only vote to have elections this year if a constitutional assembly is also approved.

But a closer look at the dynamics behind the protests shows that this “constitutional moment” is very unlikely. To understand why, it’s important to compare other instances when social unrest led to a constitutional assembly in a Latin American country.

In the Chilean case, for instance, the 2019 protests were not the first expressions of discontent within Chilean society. Social mobilization has been constant in Chile in the past 15 years, with clearly identifiable leadership and demands, like the pingüinos secondary student movement of 2006 and the 2011 protests led mainly by university students. These reflected the frustration with the differences in the quality of publicly and privately funded education and saw demands for access to free education.

Both social movements achieved tangible results, for two reasons. First, while social organizations leading the movement were mostly divorced from the parties in power, this very separation made them skilled at seeking collective action outside of party channels. Second, the Concertación, the center-left coalition in power in both instances, already contained a more progressive wing, and so it had the incentive to meet most of the students’ demands. In 2006, the government of Michelle Bachelet announced measures for education reform, and in 2018, Bachelet, again president, extended free university tuition to students in the bottom 60% of the income distribution.

In short, by the time the 2019 estallido social happened, political leaders had already demonstrated a willingness to respond to societal demands, and societal leaders had built up experience, allowing the agreement for a constitutional assembly. Chile’s experience also shows that agreeing on the necessity of a new constitution does not guarantee its success: Still a work in progress, the document is now being written with the input of an expert commission, in addition to elected representatives.

The same factors are not in place in Peru. There are no identifiable, agreed-upon social or political organizations leading the protests, and, perhaps with the exception of Perú Libre—the party that brought Pedro Castillo to power—they have no links to the political parties in office. While most Peruvians want new elections as soon as possible, Lima and the rest of the country disagree as to whether a constitutional assembly could be a potential solution to widespread discontent. Most members of Congress don’t consider a new constitution as a possibility or a legitimate way to channel the frustration many Peruvians feel. “The constitutional assembly is not going to happen,” said Hernando Guerra García, chair of the Constitutional Committee and member of Fuerza Popular, Keiko Fujimori’s party.

Looking at recent Latin American history, new constitutions only come about with the approval of the incumbent government, whether democratic or authoritarian. This occurred in Bolivia under Evo Morales in 2009, in Chile under Pinochet in 1980, and in Peru under Alberto Fujimori in 1993. But in Peru today, all parties on the right or center-right are completely opposed to the idea, and they are the majority. And while President Dina Boluarte recently announced that her government would present a bill to ensure that the next Congress implements a “total reform” of the constitution, her prime minister Alberto Otárola walked back her statements, indicating that this reform would not include an assembly.

Finally, while a new constitution can certainly nudge a country in a specific direction, it does not guarantee a better or more inclusive democracy. The constitution drafted under Evo Morales gave Indigenous communities more rights than they had ever had before in Bolivia’s history. Peru’s 1993 magna carta enshrined the structural adjustment reforms that helped the country towards economic stabilization in the 2000s. But Morales did not hesitate to approve natural gas exploration projects in Indigenous territories, such as the TIPNIS, when it was in the state’s interest to do so. Many Peruvians would say that their families did not enjoy the benefits of Peru’s past economic boom. As President Gabriel Boric has now learned, writing a new constitution is simply not enough in itself, and sometimes contrary to what the majority considers appropriate.

Peru’s protests will continue, but they are unlikely to bring about significant reforms. On the contrary, the Boluarte government has apparently managed to achieve what Pedro Castillo did not: a détente with Congress, under the common interest of holding onto power as long as possible.