This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Uruguay

Mass disappearances in Mexico reached a grim milestone in 2022, when the official number of missing persons surpassed 100,000. Lorenzo Vigas, a Venezuelan director and longtime resident of Mexico, has characterized this issue as a “deep wound,” one that has afflicted his adopted country for generations. In his latest film, The Box, he convincingly shows how no one can be spared entanglement in this decades-long crisis—and that, given the right conditions, even victims will turn into perpetrators.

The plot is deceptively simple. Hatzín, a teenage boy from Mexico City, travels alone to the north, seeking to retrieve his father’s body from a mass grave. On his way back home, with a box supposedly containing his father’s remains, he recognizes a man who looks strikingly familiar and quickly realizes there must have been a mistake. He returns the box. His father, he now firmly believes, still lives.

What follows is a gradual and rocky rapprochement between Hatzín and Mario—the doppelgänger who initially, and vehemently, denies any relation to his alleged son. Mario works as a recruiter for the maquiladoras—the manufacturing plants that dot the Chihuahuan Desert and industrial cities like Ciudad Juárez. Hiring migrant laborers for physically demanding jobs with long hours and low wages requires sleaziness and strategy. There is just no other way of getting people on board. As Mario teaches Hatzín the tricks of his trade, it becomes clear that the world of the maquilas, as they are informally called, invariably coexists with criminality and the absence of the law.

To survive, one must first master the art of deceit. “You are too honest,” Mario chides his putative son. “You shouldn’t reveal too much in this job. Don’t you ever lie?” Soon enough, Hatzín learns to hold his tongue and invent convincing excuses. He is put to the test, however, when Mario takes drastic steps to silence a female recruit. (She had complained too much about the factory conditions and attempted to organize a union-like group among her coworkers.) Complicity in the woman’s disappearance proves too much for Hatzín: He starts to come apart.

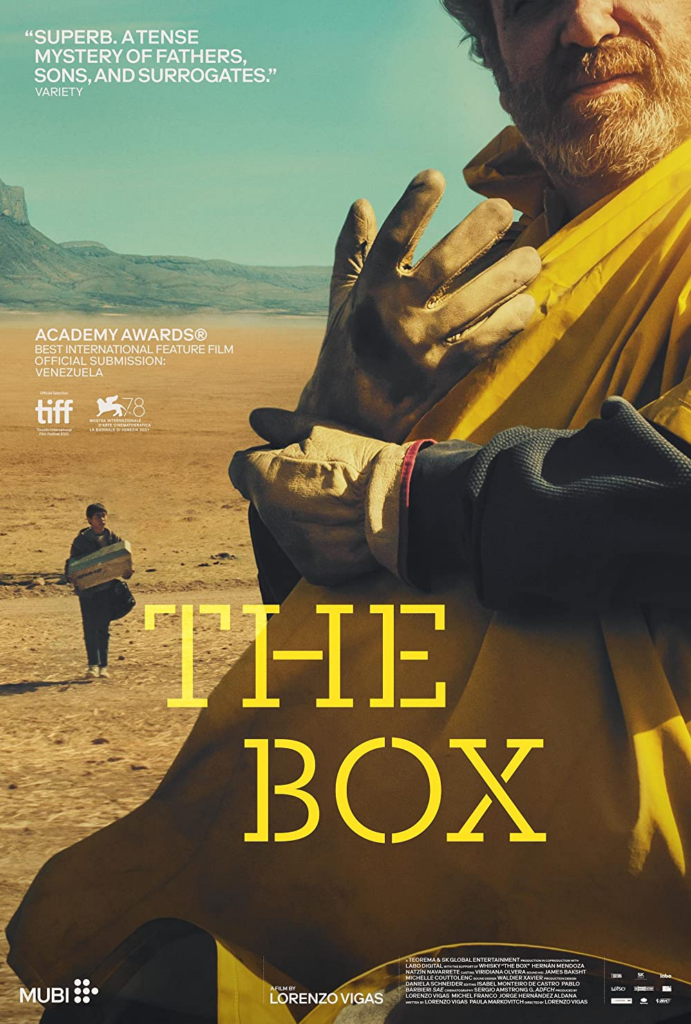

The Box (La caja)

Directed by Lorenzo Vigas

Screenplay by Lorenzo Vigas, Paula Marokovitch and Laura Santullo

Distributed by MUBI and Leopardo Filmes

Starring Hatzin Navarrete and Hernán Mendoza

Mexico, Venezuela and United States of America

AQ Rating: 4/5

Other reviewers have described The Box as a “dark coming-of-age tale.” But whatever Vigas’s film—the final entry in a trilogy about absent fathers—has to say about the transition between adolescence and adulthood is entirely incidental. The narrative focuses instead on a painful process of socialization through which individuals come to accept and even participate in the recurring cycle of violence and impunity that has led to the disappearances of thousands. In this sense, Hatzín’s trajectory has affinities with the transformation from protagonist to antagonist of Walter White in the prestige U.S. TV show Breaking Bad.

Tellingly, Hatzín’s turning point comes after the woman’s murder, when her family arrives on the scene with anguished questions. No one has described the miserable state of uncertainty the family undergoes more bitingly than the Chilean novelist Roberto Bolaño. In his magnum opus, 2666, he called this condition a “purgatory, a long, helpless wait, a wait that begins and ends in neglect, a very Latin American experience, as it happened, and all too familiar, something that once you thought about it you realized you experienced daily, minus the despair.” Hatzín must have known this feeling once too, and the irony is not lost on the viewer. In fact, he was one of the lucky ones. Most families never get to recover their lost loved ones.

Hatzín ultimately reverts to his initial decision and recovers the box. The gesture represents a desperate desire to start over with a clean slate: not merely to forget but somehow to undo the past. But such a return is impossible, the stuff of childish fantasies. Perhaps it is this kind of escapism that, multiplied many times over, partly explains why—despite decades of activism—Mexico has been unable to secure a safer future for its citizens.

—

Alvarado is a writer and former assistant editor at The Atlantic