MEXICO CITY — In a region whose history has been marred by coups and military governments, Mexico has long been a standout for its exceptional ability to maintain civilian control. But that tradition of civilian control seems increasingly fragile.

Since taking office, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has increased the size of the military and given them a number of roles traditionally occupied by civilians, ranging from security to construction and tourism. Now, the Mexican Senate has approved extending the military’s role in security until 2028, with legislation expected to be easily passed in the Chamber of Deputies.

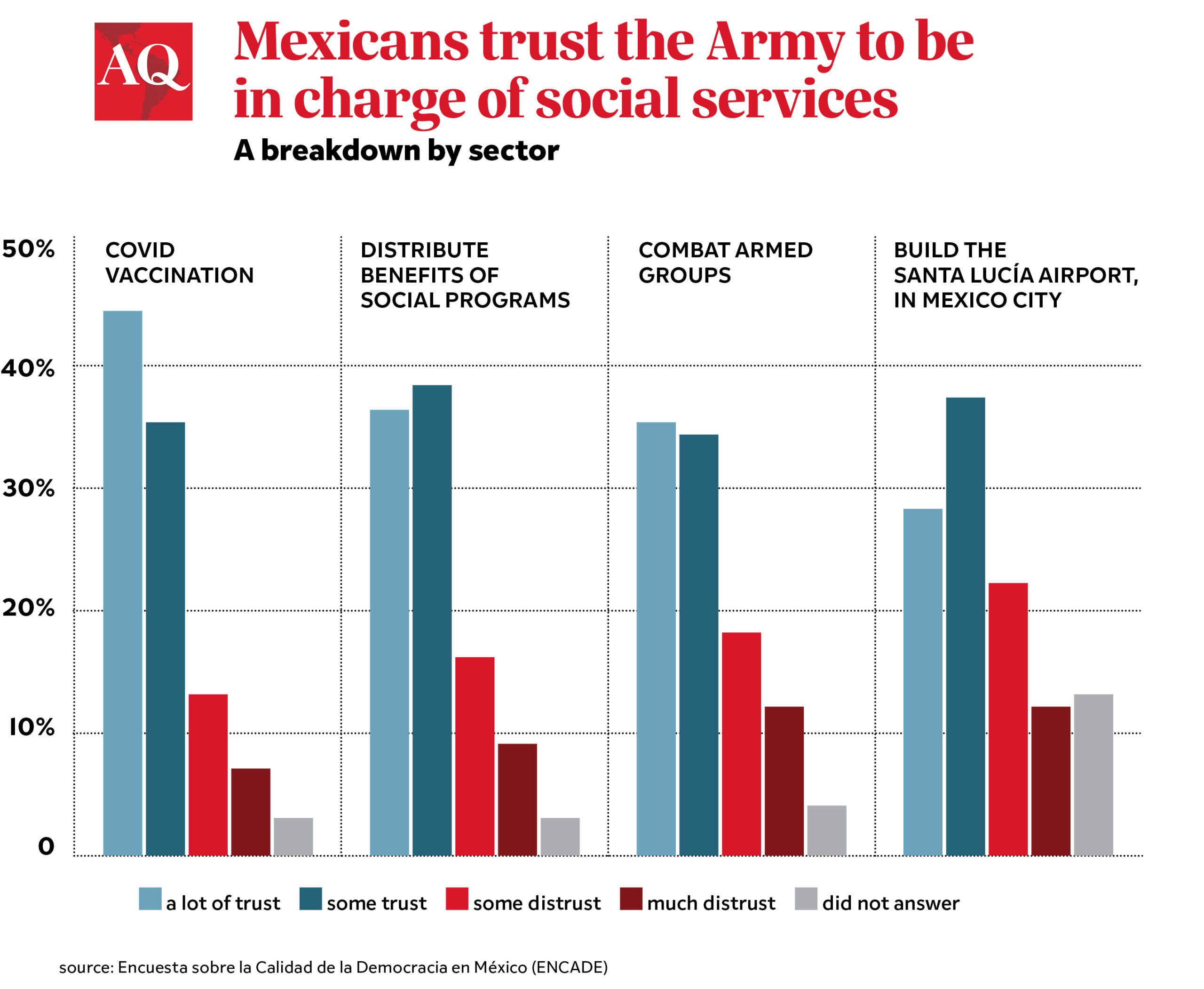

What’s even more concerning for the health of Mexican democracy is that Mexicans approve of this turn toward militarization. A survey of 2,000 Mexicans conducted in the summer of 2021 showed that the expanding role of the military in politics seems broadly accepted. The military is more trusted than any other institution: 36% of the public has a great deal of confidence in it and 71% trust it at least somewhat. Meanwhile, fewer than half of respondents trust the Congress a little or a lot, while confidence in judges, police or public officials is even lower. Perhaps as a result, Mexicans are unfazed by the proposition that the army should take over not only combating the cartels (67% have some or a lot of confidence in this idea), but also distribute social benefits (72%) and even administer public health programs (77%).

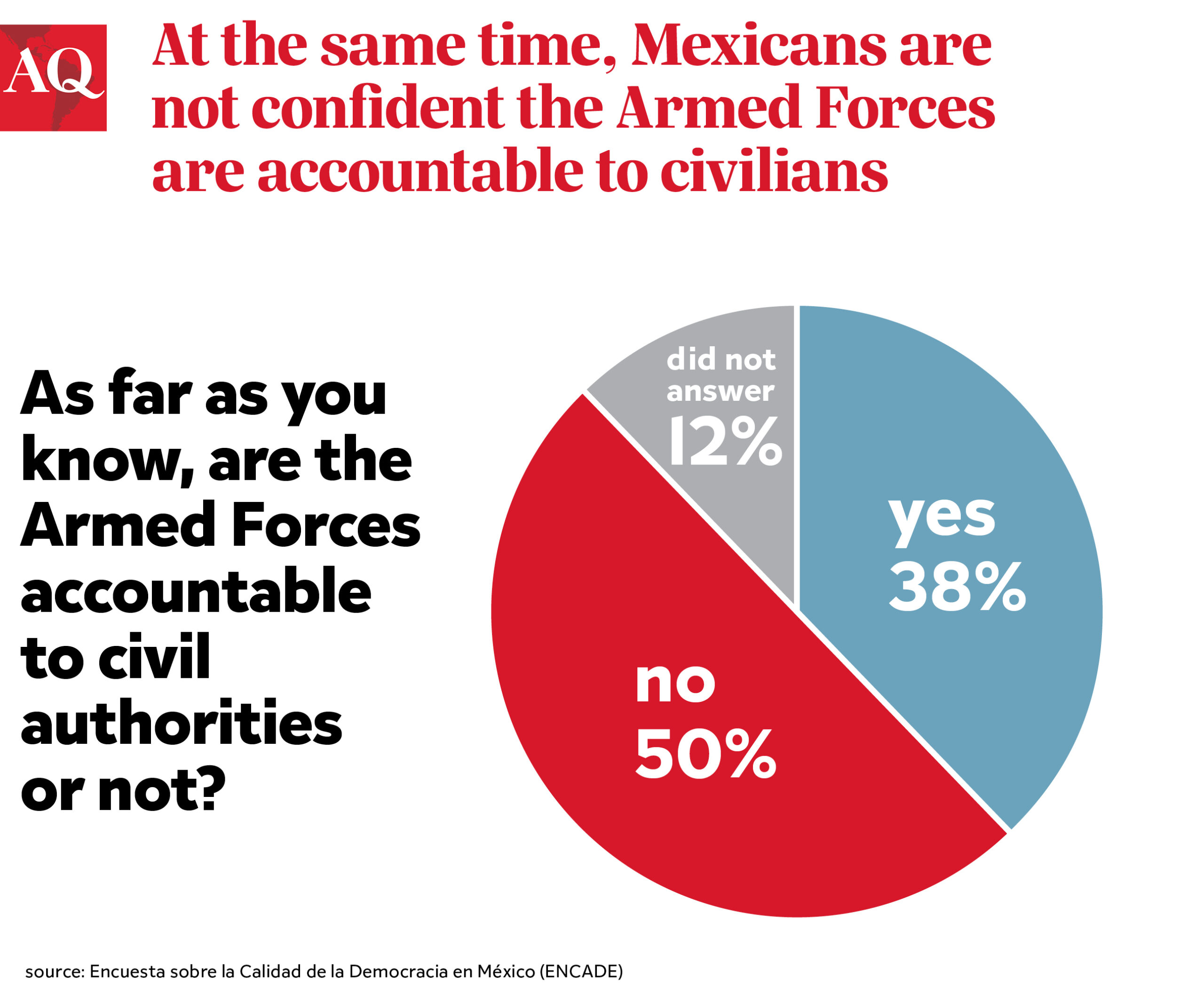

This is despite the fact that only about half of those surveyed think that military officers would “probably” be punished for civil rights violations and only 38% believe the army is accountable to civilian authorities. Half of respondents believe that the military strikes deals with drug trafficking groups.

Is this a principled endorsement of military governance over democracy? We view the phenomenon instead as a consequence of even worse opinions of democratically elected leaders. Roughly one in four Mexicans strongly distrusts the Congress, the bureaucracy and judges. One in five Mexicans strongly distrusts Mexico’s internationally respected National Electoral Institute (INE), responsible for the quality of elections. The military is accepted primarily because, as political polarization grows, the number of civilian actors fully trusted by a majority of the population has shrunk.

Mexico has never had a military coup or a formal military government in the post-revolutionary era. Indeed, the Mexican Revolution itself played a significant role in establishing these principles. The early post-revolutionary leaders, all former generals, were able to transfer military loyalties to the regime and helped to establish the PRI, a civilian-led party that governed for over seven decades. The military’s political role remained constrained, and the size of the military was limited. In 1985, Mexico had about 1.7 soldiers for every 1,000 inhabitants.

Things began to change when President Felipe Calderón (2006-2012) launched a doomed war on Mexican drug cartels, escalating the involvement of the Mexican armed forces beyond crop eradication. Calderón oversaw a major expansion in the size of the military. By the end of his term, there were 2.8 soldiers for every 1,000 Mexicans. The consequences include a steeply rising toll of murders and disappearances and a transfer to urban spaces of violence that had long existed in rural areas. Homicides in Mexico are among the highest in the region, at around 35,000 per year.

López Obrador had promised to reduce the size and scope of responsibilities held by the military. In his campaign he offered to reverse the militarization of drug policy, replacing it with economic development programs as an alternative to cooperation with the cartels. His slogan, “Hugs not Bullets” (Abrazos no Balazos) reflected Mexican weariness with the spread of violence.

Instead, militarization continues to advance. The National Guard, which he promised would function as a national police force under civilian control, will now be incorporated into the National Defense Ministry (Sedena), which will increase the number of troops under military control by approximately 50%.

Despite the fact that President López Obrador had promised to reduce the army’s influence in public safety, the number of troops deployed across the country is now more than twice as high as at any previous point in history. López Obrador has put the military in charge of tasks as diverse as building infrastructure, distributing gasoline, textbooks for basic education and fertilizers, and controlling the COVID-19 vaccine rollout.

Meanwhile, the Army currently finds itself involved in serious accusations of hacking and spying on journalists and human rights activists.

The broad and unquestioning endorsement of an expanded military role revealed in this survey, in tandem with the willingness of the government to assign the military more tasks, does not bode well for the future ability of Mexican governments to maintain authority in the hands of elected officials. While we do not anticipate a coup or the direct assumption of power by the military, we do see a significant risk that the military will assume an unofficial and informal tutelary role that might constrain elected officials from carrying out popular mandates. This would further undermine the credibility of Mexico’s representative institutions.

—

Farfán is head of security research programs at the Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies at the University of California San Diego.

Bruhn is professor and chair of political science at the University of California Santa Barbara.

Rizzo is assistant professor of political science at the University of California Merced.