Entering Courtroom 600 sent shivers down my spine.

Nuremberg, Germany is arguably the birthplace of international criminal justice. In 1945 and 1946 authorities tried and sentenced top Nazi commanders for their role in war crimes and crimes against humanity. The trials took place in the same wood-paneled room where I attended, in October, Nuremberg Forum 2022—a conference examining the history of the International Criminal Court (ICC) and its fight against impunity for grave crimes.

As I listened to these discussions, I was mindful of the atrocities that shaped my own family’s history. My Jewish grandfather fled from Poland to Argentina shortly before World War II. In what must have felt like a chilling déjà vu, my grandparents and parents then had to escape the dictatorship that gripped Argentina from 1976 to 1983. Venezuela, then a beacon of democracy, took them all in, and I was born in Caracas.

Now, times have changed, and the ICC must focus on Venezuela, whose repressive regime is making enormous efforts to forestall accountability for its abuses. The Court must maintain a delicate balance between pushing its own investigation forward and coaxing Venezuelan authorities to do so themselves. Efforts to encourage Venezuela’s judiciary to prosecute human rights abuses have so far failed to produce any meaningful results, as the country’s judiciary remains dysfunctional and lacking independence.

The ICC’s role in bringing justice on behalf of the victims of the government of Nicolás Maduro is shaped by its nature. The ICC is a court of last resort: To move forward with an investigation, its Office of the Prosecutor must first conclude that domestic courts are not genuinely investigating or prosecuting serious international crimes alleged. This is the key known as the “principle of complementarity” under the court’s founding Rome Statute, which keeps the primary responsibility for justice with national authorities.

But historically, the prosecutor’s office has articulated an additional policy goal—to serve as a catalyst for justice at the national level. This has not always been popular, but it can be a critical means to extend the ICC’s impact far beyond the cases it can take on itself. The idea is that where national authorities at least state their willingness to carry out investigations, the ICC can help stimulate progress within a nation’s own criminal justice system. In doing so, the ICC must open space for national authorities to do their own work while proceeding—and equally important, being seen to proceed—with its own analysis and eventual determination as to whether it will seek to investigate. For example, the ICC succeeded in catalyzing some important steps in domestic justice during its preliminary examination in Colombia, which began in 2004 and remained open until 2021.

Getting the balance right is quite difficult. Delays, intended to give space for national authorities to act, can backfire by allowing those authorities to stall their own proceedings or even obstruct the ICC’s work. This, in turn, can lead to perceptions that the ICC is legitimizing impunity. Past experience shows that the ICC’s influence is most constructive if authorities feel the pressure that an ICC investigation may well proceed in the absence of national progress.

The case of Venezuela

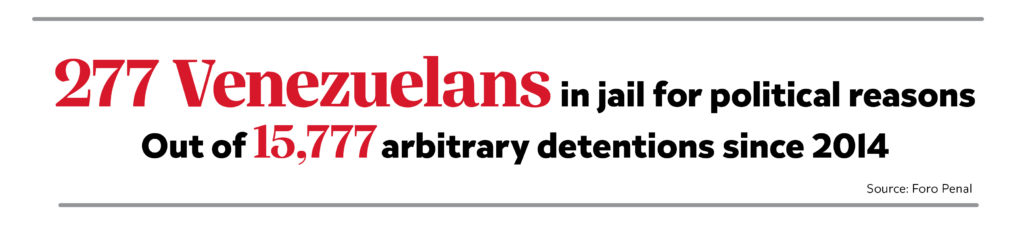

How is the ICC handling this delicate balance in Venezuela? It opened a preliminary examination in 2018 and formal investigation in 2021, and in November of this year, Karim Khan, the ICC prosecutor, sought authorization to resume his investigation into alleged crimes against humanity in Venezuela, including imprisonment, torture, sexual violence, and persecution on political grounds. The investigation had been put on hold in April, when Venezuelan authorities—in a desperate attempt to delay it—argued that domestic authorities were already investigating the crimes.

Having visited Venezuela twice, Khan concluded that “patterns and policies” of alleged crimes against humanity are not being investigated by Venezuelan authorities, that domestic proceedings appear to focus on low-level security force members and mostly on crimes considered to be of “minor” gravity. Nearly 70% of the 893 cases reported to be under investigation, he noted, are at a preliminary stage of investigation, and “progressive investigative steps” are evident in only 28. Legal reforms undertaken by the Maduro government, he concluded, “remain either insufficient in scope or have not yet had any concrete impact on potentially relevant proceedings.”

Unsurprisingly, Venezuelan authorities quickly rejected the filing. The pre-trial chamber has invited victims—including family members of those killed by security forces, those arbitrarily detained and those who have been tortured by security forces—to submit their views and observations. It has also allowed Venezuelan authorities to respond in court to the prosecutor’s request by February, before it rules on whether his office can continue with the investigation. It remains to be seen how the judges will rule.

The ICC’s interactions with national systems are complex, but this cooperation is crucial to maintain accountability. In line with the idea of “positive complementarity,” the ICC prosecutor has signaled his interest in cooperating with the Venezuelan authorities on efforts to reform the judiciary in parallel with the court’s own investigation.

But for the time being, accountability avenues remain blocked in Venezuela, where a dysfunctional judiciary—and lack of judicial independence—may significantly constrain what the ICC can achieve, when it comes to encouraging national justice. The judiciary stopped functioning as an independent branch of government when former President Hugo Chávez and supporters in the National Assembly took over the Supreme Court in 2004. Supreme Court justices, who have a say in the selection and removal of lower court judges, have openly rejected the separation of powers and consistently upheld abusive policies and practices. Some were reelected recently, based on the regime’s judicial reform to, allegedly, strengthen judicial independence.

International attention in recent days has focused on the resumption of political negotiations between the Maduro government and the Venezuelan opposition. This is for good reason: Such negotiations are essential to protecting rights in the country. But it is equally important to keep pursuing international scrutiny of abuses—so victims can eventually have access to justice, and also to create the right incentives for political negotiations to result in a successful democratic transition.

—

Taraciuk Broner is deputy Americas director at Human Rights Watch