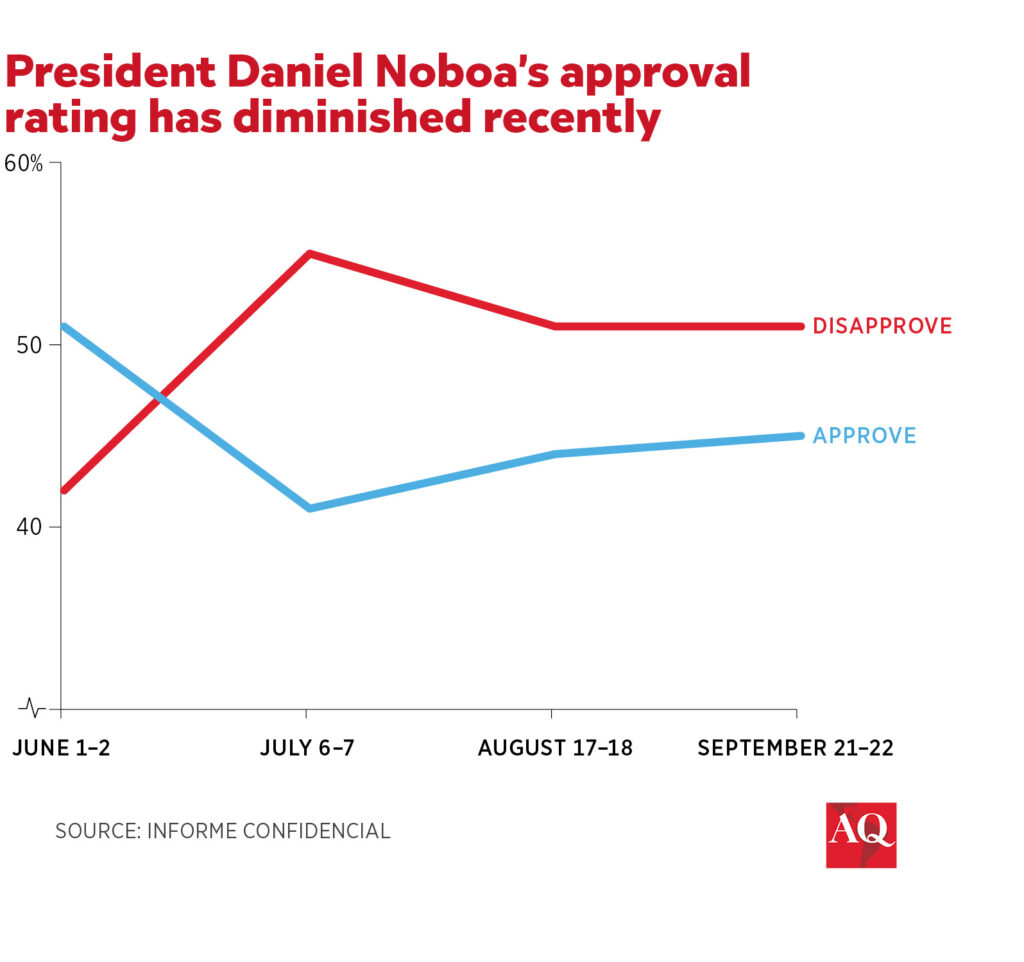

QUITO—Just a few weeks ago, Ecuador’s President Daniel Noboa seemed poised to easily win the 2025 presidential election, with most polls placing him as the frontrunner. He boasted over 50% public approval and 30% voter intention. However, a series of costly electricity blackouts around the country has abruptly changed perceptions, and recent polls show that voters are increasingly pessimistic about the future of his candidacy.

Elected last year to complete the term of former President Guillermo Lasso, who called an unprecedented snap election, Noboa has governed for just over ten months. This brief tenure has helped limit the erosion of public support. At a time when voters are disillusioned with the political status quo, Noboa remains the “outsider” of the upcoming February election, challenging traditional political forces, which he labels as “old politics.” Additionally, as the incumbent, he holds the unique advantage of leveraging government resources for advertising and enacting populist policies. For instance, he recently proposed subsidizing monthly residential power bills from December to February, which coincides with the election season. Yet, Noboa faces serious challenges, from escalating crime, an energy crisis, and a stagnant economy, which could jeopardize his reelection bid.

Crime remains Ecuadorians’ primary concern and poses the most significant threat to Noboa’s reelection despite his tough-on-crime stance. While homicides have decreased marginally since his government launched a popular “war” against criminal organizations earlier this year—which mostly called for the military to actively support police efforts in the most violent regions and within the prison system, where massacres were a major source of homicides in recent years—the numbers remain at historically high levels.

Days ago, Noboa visited the construction of a maximum-security prison in Santa Elena province on Ecuador’s west coast, where the government plans to isolate leaders of the criminal gangs operating in the country, now a hotbed for drug trafficking. “We are improving the (security) situation, and the detention centers will no longer be crime centers,” he said.

But despite his efforts, progress on this front has been slow. Government data through August shows that homicides nationwide have dropped by 17% so far this year compared to the same period in 2023—an unprecedented year for violent crime—but are still 41% above 2022 levels. The results vary by region: homicides declined in Guayaquil, Quito, Esmeraldas and Machala, but surged in Durán, Babahoyo and Manta. Other crimes, such as robberies, have decreased by 15.8% this year compared to 2023, though they remain 8.8% higher than in 2022, according to the Attorney General’s Office.

Noboa’s ability to maintain or build on these gains, particularly by further reducing violent crime, will be critical to his reelection prospects. Any worsening of the security situation or a major violent incident in the run-up to the election could severely impact voter sentiment, opening the door for other candidates. The assassination of presidential candidate Fernando Villavicencio last year shaped voter preferences by reducing support for correístas (whom Villavicencio supporters accused of being behind the killing) and provided an opening for outsider candidates like Noboa.

National blackouts

At the same time, Ecuador is grappling with a severe drought that has drastically reduced hydroelectric power generation, which typically supplies about 80% of the country’s electricity. Colombia, Ecuador’s traditional supplemental energy provider, is also facing its own power shortages, leading to a 1,000MW electricity deficit—out of a total national demand of 4,000MW. As a result, some areas have experienced blackouts lasting up to 10 hours as the government scrambles to address the crisis. Proposed solutions include revamping disused thermal power plants, purchasing new ones, and making last-minute electricity purchases from seaborne barges.

In a country where the state has long dominated power generation and distribution, the government is now calling on the private sector to step in and provide backup power and to invest in electricity generation. The government’s response to this inherited crisis, though, has been criticized for being slow and poorly coordinated, particularly in its messaging. Officials have frequently shifted their stance on the necessity and duration of the blackouts, frustrating the public. Just weeks ago, the minister of government downplayed the possibility of further outages.

This communication misstep has exacerbated the political fallout, particularly as Noboa had championed an electricity reform law last year, dubbed the “no more blackouts” law—an accomplishment that now feels like a broken promise. The economic impact of these blackouts is severe, with business associations estimating that each 8-hour power outage costs the private sector approximately $96 million. Furthermore, the worst of the drought may coincide with the lead-up to the election in early 2025, prolonging voter’s dissatisfaction.

While the security crisis is more regionally concentrated—allowing the government to direct resources and shape the narrative—blackouts are being felt uniformly across the country, regardless of social class, making them a nationwide source of frustration. This discontent could severely affect Noboa’s standing in the polls, as many voters already expressed their frustration with energy issues during the government-led referendum earlier this year, which cost him a decisive win. If the blackouts continue or worsen, they will likely become a pivotal issue that challenger candidates can exploit.

A slowing economy

Compounding Noboa’s challenges is Ecuador’s sluggish economy. The IMF projects growth of just 0.1% for this year, with the potential for contraction depending on the full impact of the energy crisis. While Noboa’s early agreement with the IMF pleased markets, stabilized public finances and provided much-needed liquidity, it has not spurred any significant economic growth ahead of the election. Meaningful improvements depend on major economic reforms unlikely to materialize until a new government—hopefully with a strong mandate—takes office in May 2025.

Despite these mounting challenges, Noboa remains the favorite in the 2025 election, although his lead is narrowing. Polls show that other candidates, such as correísmo‘s Luisa González and security hardliner Jan Topic, are gaining ground, making the race far more competitive than many expected. In the first round of last year’s snap election, Topic came in fourth place, while González lost to President Noboa in the runoff by a four-point margin. Among other factors, Topic benefited from his focus on security, while González from nostalgia for better times under correísmo, factors that could play in their favor again this time. At the very least, these difficulties may prevent Noboa from securing a first-round victory, which would have been vital to consolidating a sizable bloc in Congress to enhance governability. If in the first round on February 9, no candidate secures more than 50% of the votes or wins by 40% plus a 10-point lead over the runner-up, a runoff will be held on April 13.

Should Noboa be reelected with a weak mandate and minimal congressional representation, Ecuador may face continued political fragmentation and instability, further delaying much-needed political and economic reforms to resume a sustained growth path.