Latin America’s finance and economy ministers can’t be getting much sleep these days. Measures to maintain market liquidity and sustain the region’s economies are already underway, as governments engage in the titanic task of addressing the crisis while at the same time avoiding economic collapse. The overall message is clear: Financial aid must be deployed quickly and effectively.

But whether it’s a pandemic, natural disaster or economic emergency, crisis response tends to carry with it a high risk of abuse. Fraud and corruption can divert precious resources in times of urgent need, undermining public trust in government.

Examples of this problem abound. A recent World Bank study shows how foreign aid can end up in government officials’ personal bank accounts in tax havens. Corruption and fraud allegedly consumed a portion of the $13.5 billion donated or loaned to countries affected by the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. The U.S.’ Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimated that up to 16% of the aid spent following Hurricane Katrina was lost in improper activities. And the Washington Post recently reported serious corruption allegations involving Puerto Rico’s reconstruction program.

This should sound alarm bells in Latin America as governments shape their response to the coronavirus. Fraud and corruption have flourished following humanitarian crises in the region already – from Hurricane Mitch in Central America in 1998, to the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, to the El Niño response in the Andes in 2017.

There’s one big reason why this has been the case: Health emergencies and natural disasters generally require an easing of controls and an increase in policymaker discretion to streamline spending decisions. Governments need to accelerate the use of resources to fight crises, especially when it comes to public contracting needs that are too urgent to follow traditional norms. This makes sense, but the rush to spend can also lead to big problems of its own.

Studies suggest, for example, that reducing controls and increasing discretionary spending generate more opportunities for collusion among bidding firms, more bribes in exchange for inflated prices, and an increase in other types of graft. The need to act quickly and flexibly can create a state of general confusion among those responsible for negotiating contracts and making purchases, opening still more opportunities for illegal practices.

Some estimates suggest that corruption consumes between 10% and 25% of the value of public contracts under normal circumstances. This percentage is likely much higher in emergency situations.

The health care system is especially vulnerable, where a recent study estimates that at least 10% to 25% of global spending is lost through corruption – hundreds of billions of dollars every year. Problems of information and competitiveness make the sector particularly vulnerable to corruption – including fraud in hospital construction, drug approval processes, medicine prescriptions, beneficiary enrollment, and the private resale of supplies from public hospitals.

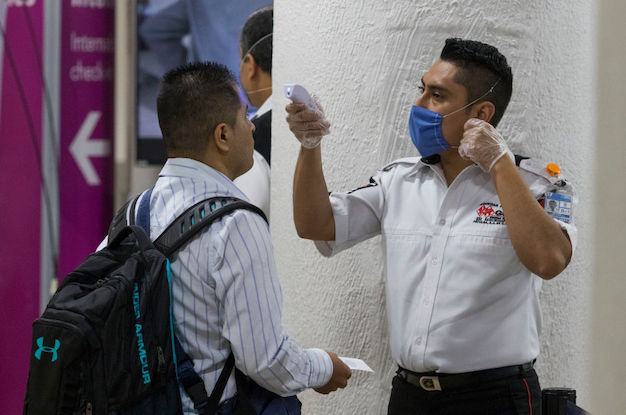

With the coronavirus, these risks may become even more acute on multiple fronts, such as the purchase and distribution of medicines and equipment to carry out epidemiological tests.

Technology as a game changer

There is no silver bullet that will eliminate the risks of fraud and corruption in emergency situations, but there are measures that the region can take to strengthen its institutional response. To start, disclosure of final beneficiaries on the part of companies and subcontractors would help. So would strong audit and oversight practices, and the creation of centralized agencies to coordinate relief efforts and monitor the use of resources.

Transparency should play a central role, especially when it allows citizens to access reliable and updated information on the resources available in the emergency. Digital tools can help policymakers integrate and visualize data, identify possible red flags and increase the traceability of resource flows. They can also allow anyone to publicly share data, which creates an added deterrent to illegal activities.

In the U.S., for example, stimulus measures following the 2008 financial crisis were accompanied by a digital platform that helped increase accountability at the federal level. At the state level, these platforms were also key for monitoring policymakers’ actions. At least 49 states developed digital tools with information on federal funds associated with stimulating the economy.

Latin American and Caribbean countries can take advantage of existing digital platforms, such as the Interamerican Development Bank’s (IDB) MapaInversiones, which is already in use in Colombia, Peru, Costa Rica, Paraguay, the Dominican Republic and elsewhere. Citizens, public officials, the private sector and other stakeholders can interact with the platform through simple and intuitive feedback mechanisms. For example, anyone with a smartphone can upload a photo showing whether there are available beds and vaccines at a given hospital.

Transparency will not completely remove the risk of corruption in emergency management. But digital technologies can substantially reduce the asymmetry of information and deter irregularities. Most importantly, accountability will help increase the likelihood that resources reach those who need them most.