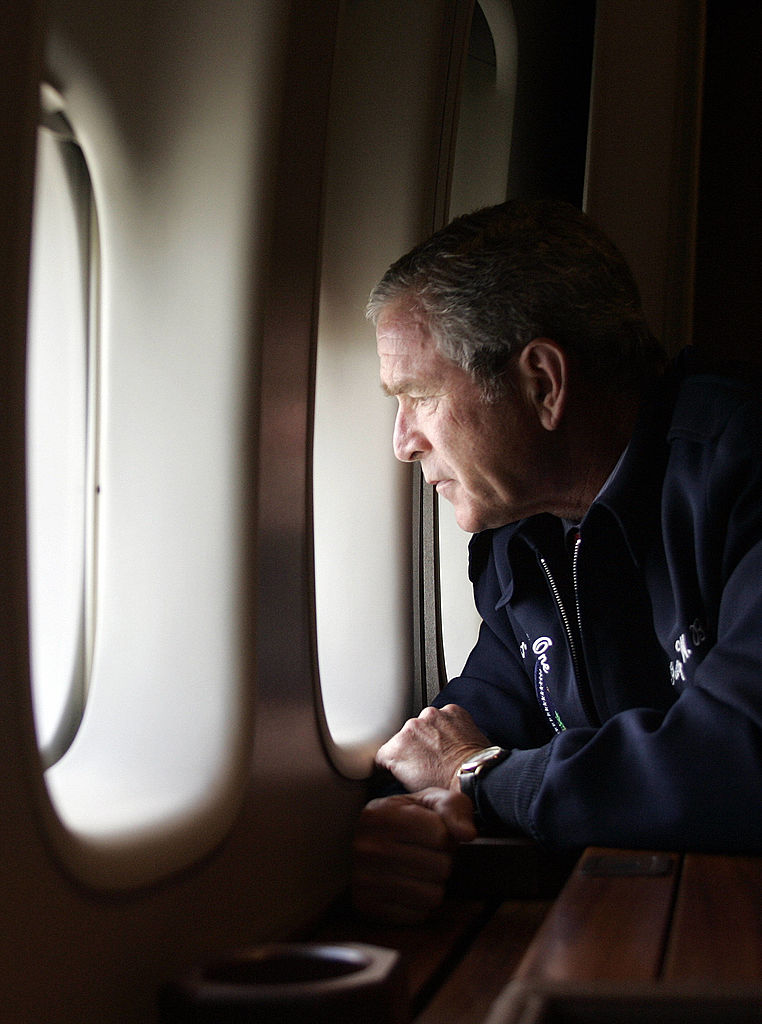

When Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans on the morning of August 29, 2005, George W. Bush’s presidency was already in trouble. But the images of a proud American city flooded under nine meters of water, as people shouted in vain for help from their rooftops, shocked the nation. More than 1,000 died. The Bush administration’s agonizingly slow, ineffective response was encapsulated by an iconic photo of the president flying above the wreckage in Air Force One, staring impotently out the window.

Soon after, Bush’s approval ratings fell under 40% for the first time – and they would never fully recover. For many Americans, Katrina was the last straw, even more than the Iraq War, definitive proof that his was an incompetent and dishonest government. Majorities began to say in polls that Bush could not be trusted in a crisis. Nothing would ever again change their minds. Bush’s ratings continued to sink for the rest of his presidency, to below 25% by the time he left office in 2009.

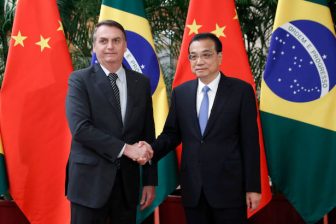

Recent polling in Brazil raises the question of whether President Jair Bolsonaro has already crossed a similar Rubicon. The main culprit is not a hurricane, of course, but a virus – one he famously called “a little flu” and downplayed nearly every step of the way. Now, Bolsonaro’s approval rating has sagged into the 20s in several polls, which also show him losing the October 2022 election by more than 20 points to his nemesis, leftist former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Does Bolsonaro still have time to stage a comeback? Or have most Brazilians essentially made up their minds, and decided to turn the page?

It sure looks to me like the latter. 59% of respondents in last week’s Datafolha poll said they would not vote for Bolsonaro “under any circumstances,” a number that rose to 64% among women and 70% among the young. (Overall, just 38% said the same about Lula.) A Bush-like 63% say Bolsonaro is “incapable of leading the country,” while majorities also describe him as dishonest (52%) and unprepared (62%). It is one thing for a president to lose popularity; it’s another to lose respect. Once gone, it rarely comes back.

No Ph.D. is necessary to understand how we got here. Bolsonaro’s numbers have been steadily eroding since January, when an emergency social program was scaled back just as the so-called Manaus variant took the pandemic into its most brutal phase. COVID-19 has killed at least 590,000 Brazilians, the world’s second-highest toll behind the United States. On a per-capita basis, Brazil is also among the 10 countries worst hit. Today, cases and deaths are finally falling, thanks to a belated but successful vaccination drive. But by constantly questioning vaccines’ effectiveness and shunning the jab himself, Bolsonaro has accomplished the singular feat of receiving little to no political credit for the improvement.

What’s happening in the economy is also critical. If you look at GDP numbers, Brazil seems like a relative success story – shrinking less than any other major Latin American economy in 2020 (-4.1%) and rebounding nicely in 2021 (+5%). But those numbers disguise vast inequalities. With the virus preventing a return to normal, and Bolsonaro’s constant disruptions scaring away investment, unemployment has stayed near record highs at 14%. The estimated number of Brazilians suffering from hunger has nearly doubled since Bolsonaro was elected in 2018, to 19 million people. Meanwhile, inflation is running at 9%, the fourth-highest rate in Latin America behind only Venezuela, Argentina and Haiti, with a devastating effect on real wages. Especially in poorer areas like the Northeast, all this has fueled nostalgia for the 2000s when Lula was president, a period marked by massive corruption scandals but also the growth of the middle class. Polls suggest that millions of Brazilians seem to be concluding: “We thought Lula was bad, but good God, Bolsonaro is worse. Bring the Bearded One back.”

Bolsonaro’s team believes it has at least one more ace in the hole – plans to boost the payout of the Bolsa Familia social welfare program, possibly by as much as 50%, starting in December. This could work; the generous aid program of 2020 clearly boosted Bolsonaro’s ratings. But that was before the tragic surge of 2021 that saw hospitals and cemeteries overflow, a national trauma that no money may be able to fully erase. Meanwhile, several economists have slashed their GDP forecasts for 2022 to below 1%, diminishing hopes for a pre-election consumption boom. Everything about Bolsonaro’s behavior suggests he is feeling insecure – from his constant questioning of Brazil’s electoral system to his vows (since retracted) to disobey Supreme Court rulings and his warnings that a rupture with the Constitution may be imminent. Bolsonaro recently said he sees only three possible outcomes for himself: “prison, being killed, or victory.” He is not acting like he thinks the third option is the most likely.

The pandemic has created a tough environment for incumbents everywhere – as evidenced by recent election results in Argentina and Peru, two other countries in COVID’s tragic per-capita “top 10.” It’s often said that presidencies boil down to one thing. For every global leader of the early 2020s, they will be judged by how effectively they limited the damage from the worst pandemic in a century. Over the last 18 months of denialism, antagonism and inattention to the crisis, Bolsonaro seems to have convinced most Brazilians that he is simply incapable of keeping them safe, an opinion they seem unlikely to change. And this is where our two stories diverge: George W. Bush had his “Katrina moment” a year after he was reelected. Bolsonaro’s may have arrived a year before, with profound consequences.