This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on trends to watch in Latin America in 2025 | Leer en español | Ler em português

Latin America’s biggest risk this year resides not in the region itself, but in a terracotta-roofed resort some 110 miles to the north—in Palm Beach, Florida.

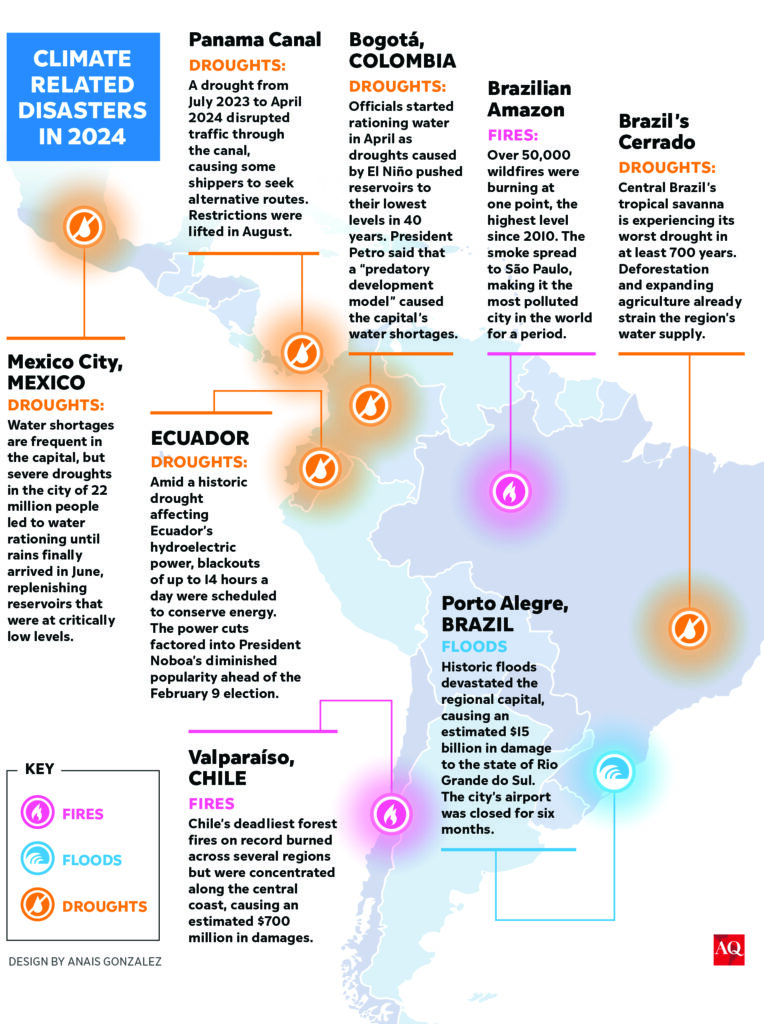

The return of Donald Trump is not the only trend likely to shape Latin America in 2025. Climate change is disrupting the region like never before, affecting presidential elections in Ecuador, shipping routes in the Panama Canal and Strait of Magellan, and harvests in Argentina and Brazil. Organized crime, an old scourge, is evolving in new ways—compromising governments and economies alike. An unexpectedly steep plunge in birth rates is raising questions about the viability of pensions, and the region’s long-term growth prospects.

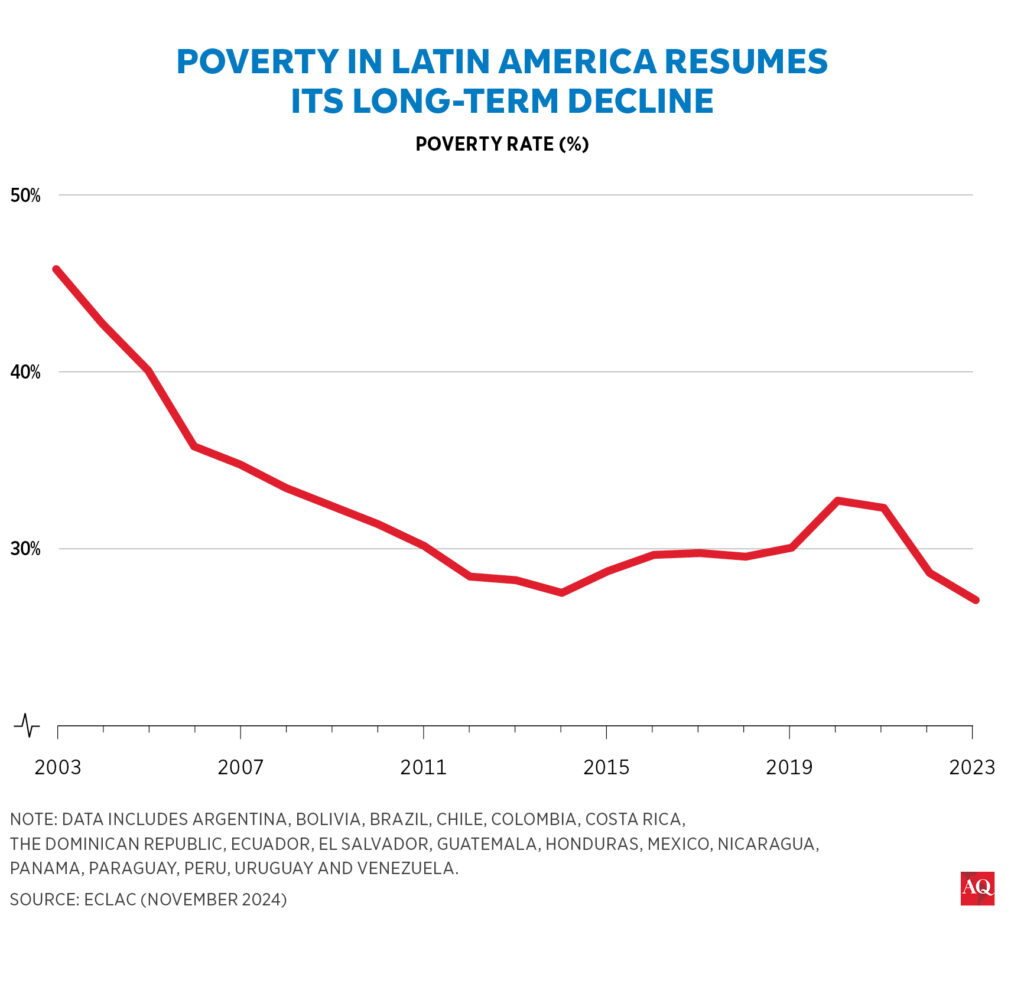

There are trends to celebrate, too. Inflation continues to come down across most of the region, as do unemployment and poverty. Argentina’s economic rebound under President Javier Milei, if it holds, would revive one of the region’s long-dormant giants, and provide a reform blueprint for some other countries, too. Latin America remains blissfully far from the world’s wars and other hotspots, with resources the world needs to feed a growing global middle class and fuel the energy transition.

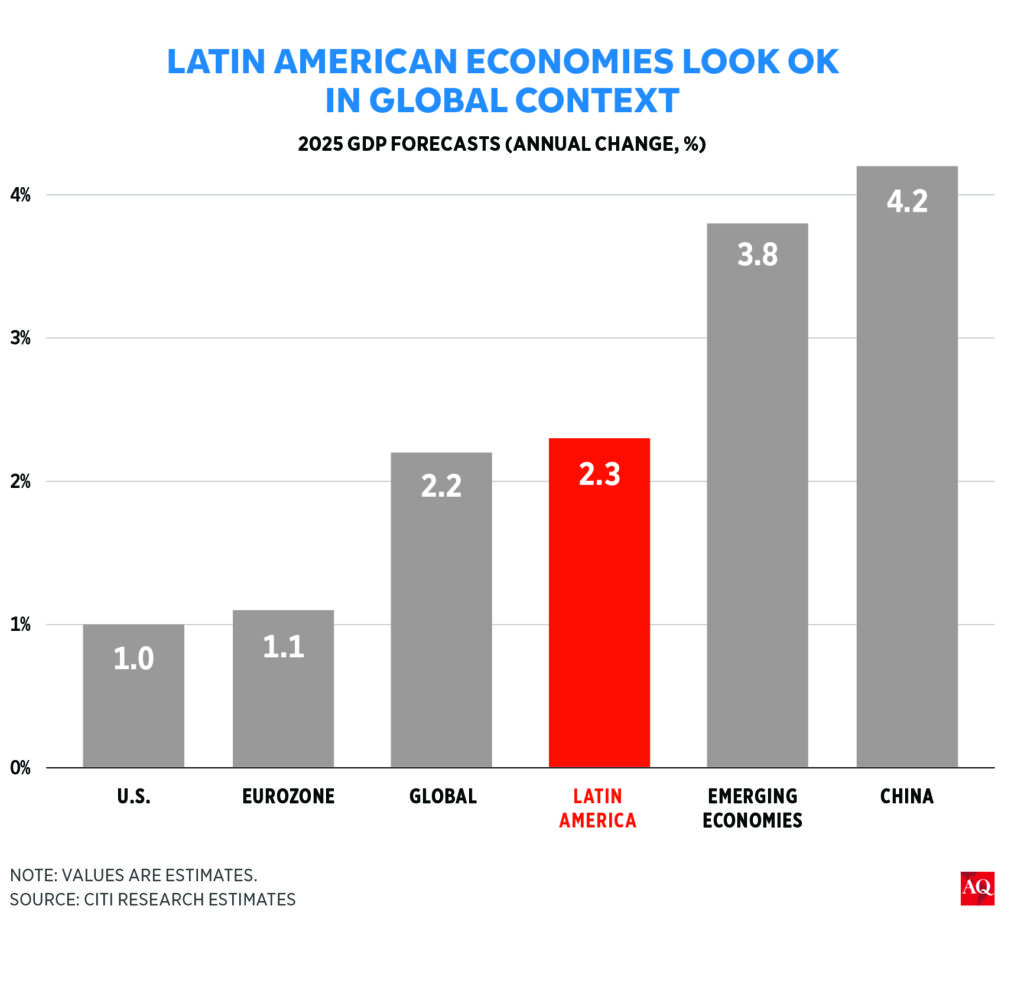

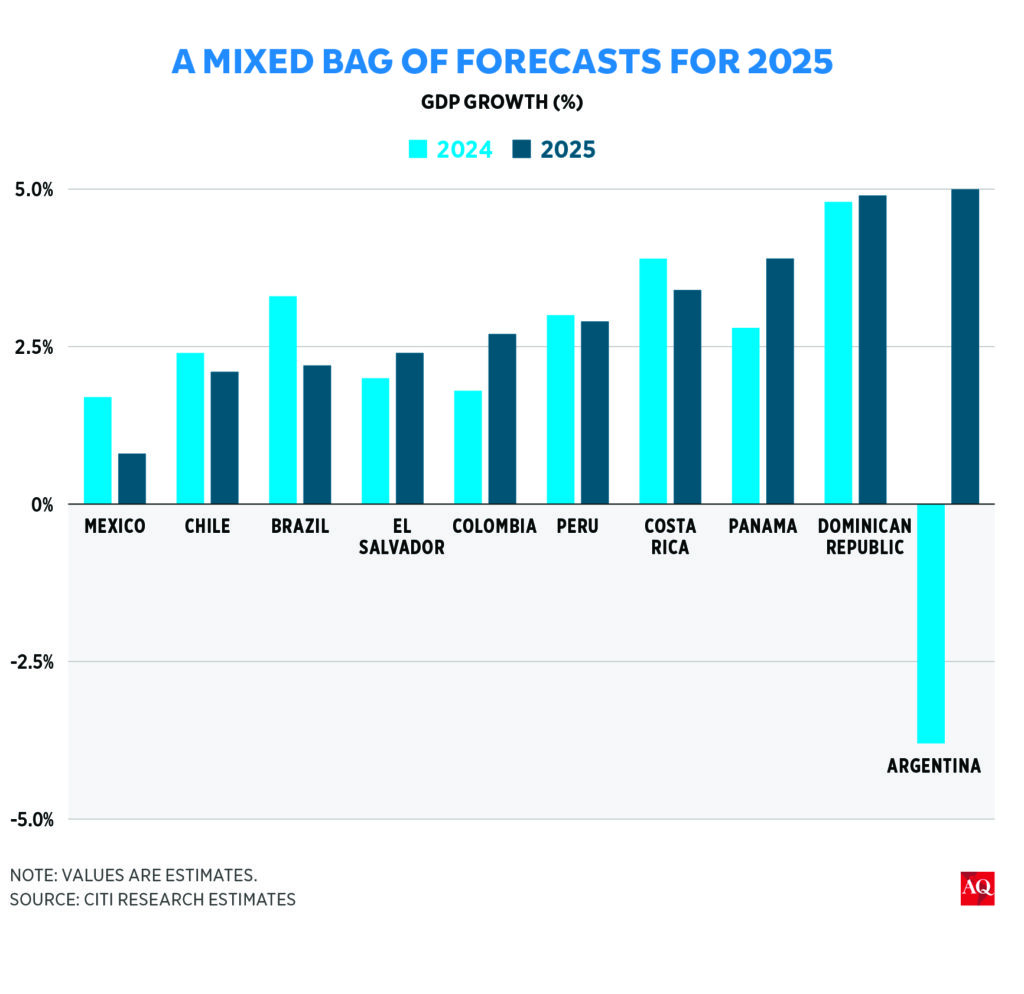

Add it all up, and 2025 looks like a somewhat positive year for Latin America—with regional GDP expected to grow about 2.5%, a touch better than 2024 (2.1%) and the average rate of expansion over the past decade (0.9%).

That would probably still make Latin America the world’s slowest-growing cluster of emerging markets, a title it has held for several years. But it’s also a region where stability is never taken for granted, and the pervasive pessimism of the late 2010s and pandemic era has given way to a little more hope.

“It’s not a crisis mood. People are not complaining that this is the end of the world. It’s like, things are not perfect, but they’re not bad either,” Mauricio Cárdenas, a former finance minister of Colombia, told me from Bogotá following a week that also took him to Paraguay and Peru.

“Interestingly, what people don’t know is whether with Trump things are going to get better or worse. There’s a lot of uncertainty,” he added.

For Americas Quarterly’s annual regional overview, I spoke to about two dozen leading figures in politics and business around the Americas. The mood seemed to vary more than usual by country, with concern in regional giants Brazil and Mexico, but considerable optimism in some smaller countries including the Dominican Republic, El Salvador and Uruguay.

Nearly everyone agreed the main question mark revolves around the man in the White House—whether he will follow through on tariffs and other threats, or perhaps pursue a more benign strategy of integrating supply chains and cooperation on security issues.

“If you were to do the outlook for Latin America in 2025, and you only look at the economics, Latin America would look relatively OK,” Ernesto Revilla, Citi’s chief economist for the region, told me recently on the Americas Quarterly Podcast, calling Trump “clearly the biggest risk.”

Based on these interviews, and a review of recent reports from the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) and other institutions, here are the four trends that seem most likely to shape events in Latin America this year:

1. Navigating Trump

“How worried should we be?”

I’ve heard this question a lot since November, including from business leaders and politicians throughout Latin America who rather like Donald Trump. Indeed, the question recognizes that Trump is an unpredictable disruptor willing to challenge even reliable allies—as evidenced by his surprising December threat to try to take back the Panama Canal.

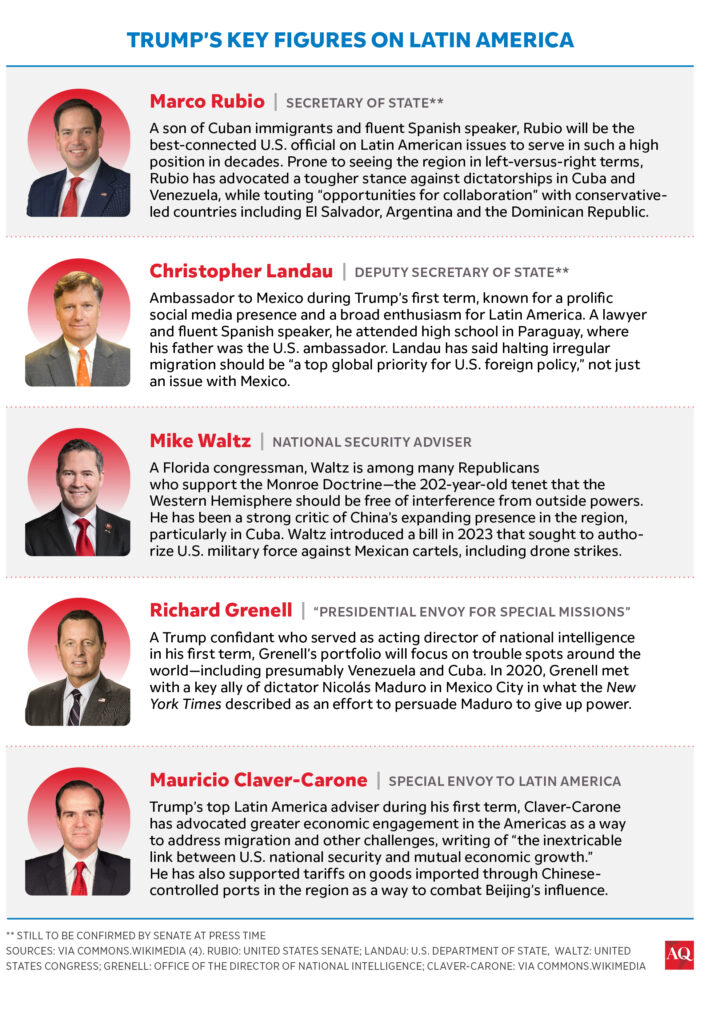

Overall, Trump’s top domestic priorities of reducing migration and drug flows mean he will be more focused on Latin America than in his first term—and perhaps more than any U.S. government since the 1990s. Trump’s Cabinet is unusually filled with officials who know the region well, and whose interventionist ideas such as the Monroe Doctrine could be used to justify tariffs, sanctions and even limited military action.

As for which countries are at risk … it’s probably best thought of in tiers.

Mexico is alone in the first tier. Uniquely in Trump’s crosshairs because of the border, and also singularly vulnerable because of extensive trade and manufacturing links, any confrontation could send Mexico’s economy, already vulnerable due to fiscal concerns and souring investor sentiment under new President Claudia Sheinbaum, tumbling into recession.

“I think there’s an enormous underestimation of the risks of what Trump 2.0 might mean to Mexico,” Revilla told me.

In the second tier are the socialist dictatorships of Venezuela, Cuba and Nicaragua—although no one knows how aggressive an approach Trump and his team will take. Some observers believe he will avoid a return to the “maximum pressure” policies of his first term, for fear of triggering an even bigger wave of migration.

The third tier includes a desire to help conservative allies such as Javier Milei of Argentina and Nayib Bukele in El Salvador. At the same time, Trump is likely to antagonize non-aligned leaders he sees as weak and sympathetic to China, such as Colombia’s Gustavo Petro, Brazil’s Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Peru’s Dina Boluarte.

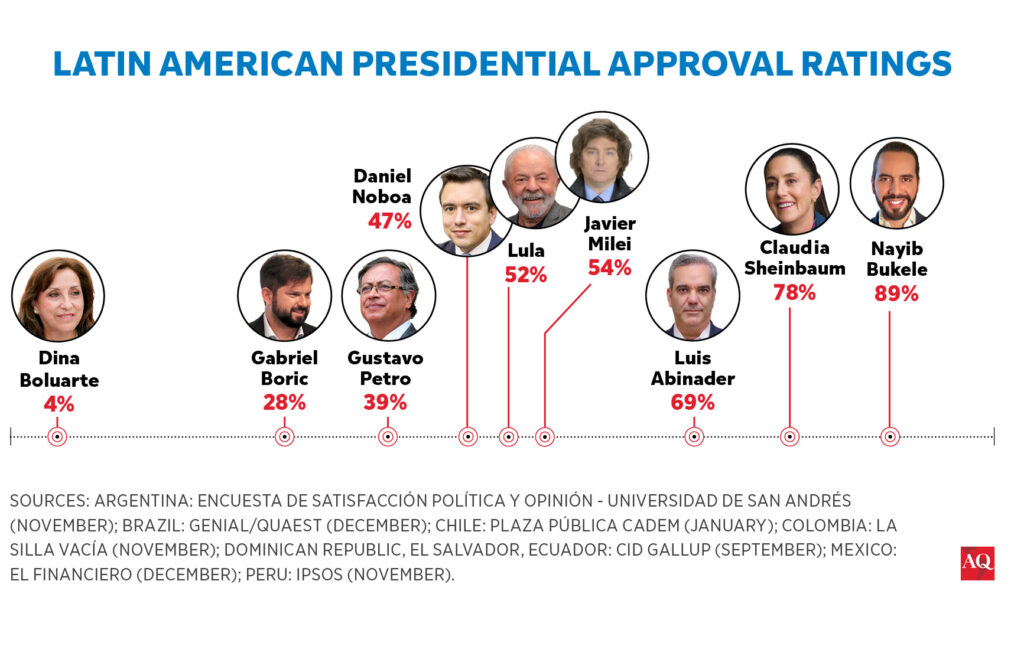

Few of these leaders seem likely to just roll over. Presidents across Latin America are generally more popular than they were a few years ago, and Mexico’s president has said she is willing to retaliate with tariffs of her own if necessary.

For countries that manage to navigate the tensions, there could be cooperation on security issues and nearshoring deals. As one official who served in the first term told me: “There will be a faction in Washington urging him to see Latin America not just as a threat, but an opportunity.”

2. A disruptive climate (literally)

Climate change is not a new issue, but 2024 was the year it seemed to “graduate” to become a major political and economic risk in Latin America.

Take the case of Ecuador. In September, conservative President Daniel Noboa enjoyed popularity above 50% and seemed to be cruising to reelection this February. But then Ecuador’s worst drought in at least 60 years impaired the function of hydroelectric dams, resulting in blackouts lasting as long as 14 hours a day over the course of several weeks. Noboa’s numbers plunged, and the left is now within reach of returning to power.

Also last year, a major regional capital and metropolitan area of 4 million people in Brazil, Porto Alegre, was devastated by floods that closed its main airport for six months and had an impact on national GDP figures. Elsewhere in Brazil, the problem was drought, with Amazon tributaries falling to their lowest level in 120 years; UNICEF estimated more than 400,000 children in Brazil, Peru and Colombia were left without access to school or health care because rivers were too low to be navigable. These conditions contributed to the worst fire season in the Amazon since 2010.

Across the region, no country—or sector of the economy—was immune. Drought disrupted shipping through the Panama Canal, caused historic wildfires in Chile that killed 130 people, and damaged harvests throughout the region. Even Bogotá, a city known for its regular rains, had to resort to water rationing.

El Niño and deforestation were also factors in last year’s disasters, but few scientists doubt climate change was a major cause. The IADB called Latin America and the Caribbean one of the “world’s most vulnerable regions to climate change” and said related disasters were capable of reducing up to 0.9% of GDP of smaller countries, and as much as 3.6% of Caribbean nations, while also driving millions to migrate in coming years.

What does it mean for investors? Even more uncertainty for economic and political risk in a region already known for it. Some also speak of a more disastrous “tipping point” in which fires cause the Amazon forest to lose the critical mass it needs to generate rainfall, disrupting weather patterns throughout South America in a more permanent way.

That said, climate change is also an opportunity for the region, which possesses the minerals such as lithium necessary to fuel the energy transition. Worsening disasters may force the world to continue to reckon with climate change, even with a skeptic in the White House. The 2025 United Nations climate summit will take place in Belém, in the Brazilian Amazon, giving the region’s leaders, several of whom are not on speaking terms, a chance to coordinate more effectively.

“Conserving the Amazon is not for the left, nor for the right, nor for the center—it is a moral duty,” former Colombian President Iván Duque, a conservative, told a recent conference.

3. “Re-organized Crime”

Organized crime is another issue that has been part of Latin America’s landscape for decades—but is evolving in new ways.

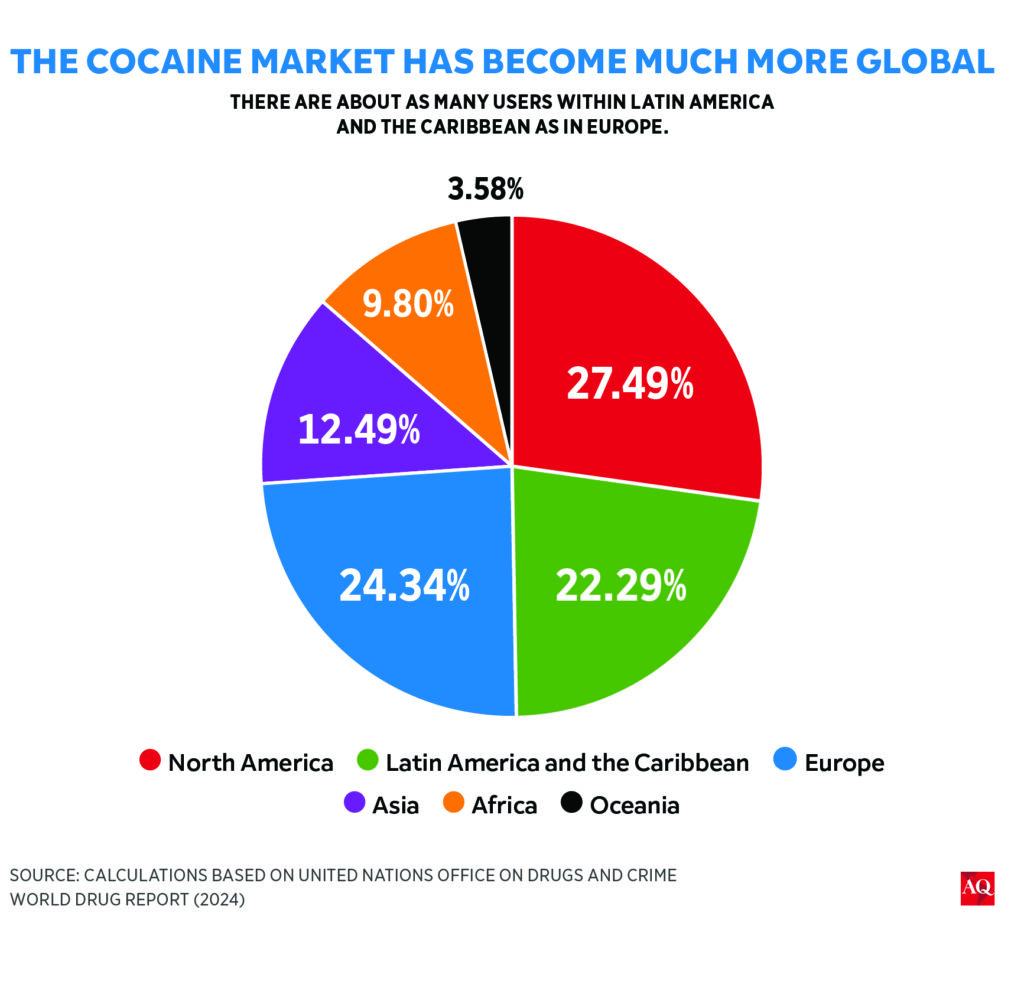

Indeed, cartels have enjoyed a massive boost in income over the past decade as cocaine production has more than doubled, according to the United Nations. Meanwhile, cocaine is not just flowing northward anymore to the United States and Europe—but south, east and west to Asia, Africa, and to Latin American nations that have themselves become major consumers of the drug.

The changes have been seismic. New smuggling routes transformed previously peaceful nations such as Ecuador and Chile into epicenters of violence as cartels battle over control of ports like Guayaquil and San Antonio. Even Costa Rica, long thought of as one of the region’s most placid countries, with no standing army, has often been the world’s leading transshipment point for cocaine, driving homicides up 53% since 2020.

The flood of new money has seeped ever deeper into politics at the local and national level, observers say.

“We’ve always had criminal cartels, but they’ve never been so close to governments,” Moisés Naím, the longtime observer of regional politics and former Venezuelan minister, told me. “Government capture by criminals has now reached unprecedented levels.”

Meanwhile, gangs are diversifying into new areas—a phenomenon that Will Freeman, an AQ columnist and fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, has called “re-organized crime.” Illegal gold mines in Latin America now account for 11 percent of global gold production, producing a windfall even greater than cocaine in Colombia and Peru. Cartels are also deeply involved in the smuggling of migrants north to the United States.

The impact on day-to-day life has been enormous. In Peru, the amount of money spent on private security now exceeds the national budget for police, Luis Miguel Castilla, a former finance minister, told me. He said the pressures of illegal mining also threaten to disrupt Peru’s legitimate copper sector, the world’s second-largest behind Chile.

Overall, crime and violence now cost Latin America and the Caribbean an estimated 3.4% of GDP annually—discouraging tourism and investment, steering funds toward security instead of productivity, and contributing to emigration, according to a December report by the Inter-American Development Bank. The losses are the equivalent of 80% of the region’s education budgets, and double its social assistance spending.

There does seem to be a shift underway in the public’s tolerance for the status quo. El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele, who has built new prisons and jailed nearly 2% of the adult population, is frequently cited in polls across the region as a model to follow. While it’s early, conservatives are favored to win upcoming elections in Chile in 2025, and may have the upper hand in Brazil and Colombia in 2026.

4. Resilience

And yet … for all the risks and challenges, most Latin American economies are in decent health.

Beyond the moderate GDP growth, average inflation in the region fell to about 3.4% last year, down from a peak of 8.2% in 2022. Most central banks are expected to continue cutting rates this year, with Brazil a notable exception. Capital flows are at healthy levels, with current account deficits across the region averaging below 1% of GDP and international reserves at “comfortable levels in most countries,” according to the International Monetary Fund.

Throughout Latin America’s history, good macro numbers have sometimes failed to translate into better lives for everyday people. But average real wages rose in 2024 in seven of the nine regional countries tracked by the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. Poverty seems to have resumed its decades-long downward trend.

As a result, the vibes are pretty good: The percentage of Latin Americans who are optimistic about their personal economic future reached 52% last year—an all-time high in the 30-year history of polling firm Latinobarómetro, which tracks sentiment in 17 countries across the region.

Foreign investors remain somewhat optimistic too, showing interest in a commodities-rich region that has, at least so far, managed to transcend the tensions between Washington and Beijing. Saudi Arabia held a major investment conference in Rio de Janeiro in June, announcing a raft of initiatives. The opening of the port of Chancay in Peru may herald a new era of trade with Asia, although it is now in the crosshairs of the Trump administration.

Overall, Latin America received 15% of the world’s foreign direct investment (FDI)—double its relative share of the world’s economy—in 2023, the last year data was available, according to the UN. Commodities and minerals critical for the energy transition were the biggest sectors, with green hydrogen and green ammonia also attracting major funds.

The storm clouds around the region’s two biggest economies are major question marks. Under the new Sheinbaum administration, Mexico’s economy is slowing. Growing worries about Brazil’s fiscal management under Lula may finally derail an economy that has otherwise surprised to the upside since the pandemic, growing about 3% a year.

As always in Latin America, there are two ways to see the status quo. The IADB estimates the region’s long-term growth rate around 2%, which it calls “insufficient to meet the rising demands of the growing population.” Productivity growth, public investment and human capital all remain challenges.

But it’s also, as ever, a place of opportunity for those who can live with risk and uncertainty. “Every year we have these storms,” Angela Mercurio, who runs a small chain of bakeries in Mexico City, told me recently. “But we’re still here. We’re still growing.”