This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on supply chains

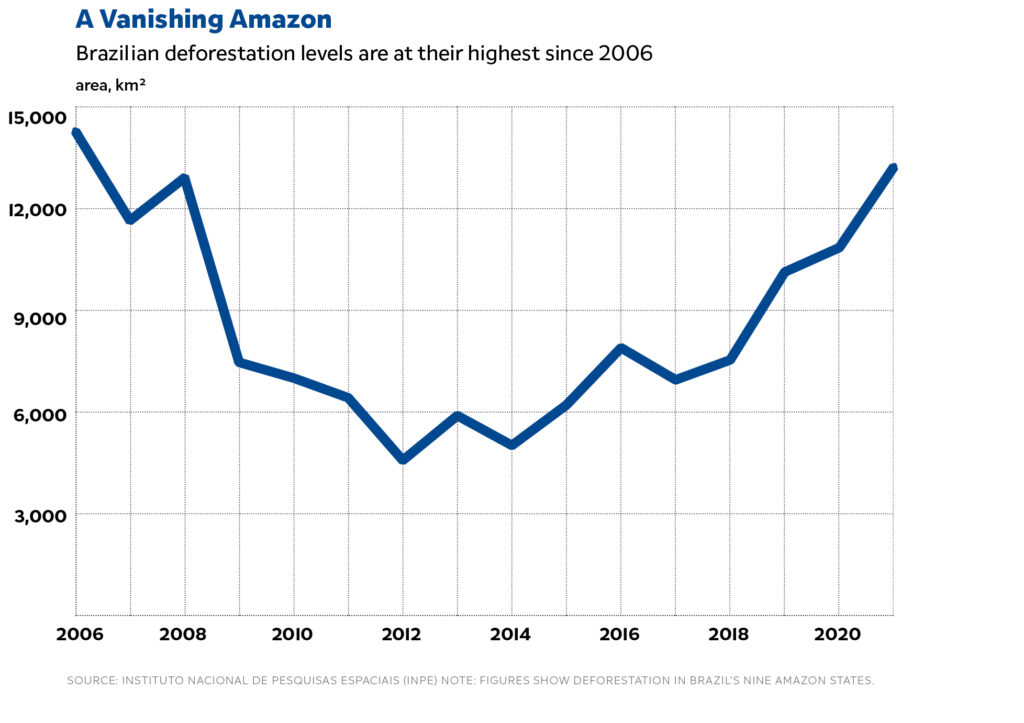

The recent history of the Brazilian Amazon is one of rapid change. Over the last 50 years, the proportion of original rainforest that has been cut down increased from a mere 0.5% in 1970 to more than 21% as of 2021. The accumulated destruction—totaling more than 205 million acres—covers an area the size of Italy and Spain put together.

Over the same period, the population of the Brazilian Amazon has quadrupled, reaching 28 million people in 2020. Not only has this process taken place in a disorganized manner, it’s also been marked by serious social conflicts—and has resulted in the worst of all possible scenarios: environmental destruction, a low quality of life for the population and an economy that both lacks dynamism and produces extremely high carbon emissions.

The current situation poses huge challenges, no doubt. But it’s also the necessary starting point for any realistic plan that has a chance of turning things around—and matters are far from hopeless. Within each of the factors contributing to the current scenario, there’s something that could be leveraged to take a step towards better, more sustainable regional development.

In crisis, there’s opportunity: You might call this the paradox of the Amazon.

Turning weaknesses into strengths

This paradox has three key elements: First, there is still a vast area of remaining rainforest. Although accelerating and uncontrolled deforestation puts its future at risk, the Amazon remains the largest tropical rainforest in the world.

Second, the region has a potential demographic dividend at its disposal. There is a growing majority of economically active people (those aged between 15 and 64) relative to children and seniors. But so far, the economy of the region has wasted this potential benefit, offering little access to jobs and good salaries for much of the population.

And third, the excessive deforestation of recent years has left behind a vast area, equivalent to the size of California and Oregon combined, of bare and badly utilized land. This area by itself is much more than what is necessary for agricultural production—meaning further deforestation is simply not necessary.

These three factors—the stretches of remaining forest, the presence of underutilized areas, and a young population—are advantages for the Brazilian Amazon region. They should be at the center of plans to ensure the sustainable future of the region.

But to take advantage of the remaining forest, the first priority is to put a quick stop to deforestation. Not only bad for the environment, it generates neither jobs nor value. Quite the opposite: It is associated with theft of public forest lands, predatory logging and other illegal activities. It also contributes to the crisis of violence that is menacing the region, and damages the business environment in the Brazilian Amazon, driving away investment and incurring social costs.

The good news is that Brazil already knows how to control deforestation. The country already does this in an effective and cheap way, by planning and creating protected areas, and also through satellite monitoring and fines for violators. And significantly, as deforestation decreased by 80% between 2004 and 2012, the agricultural GDP of the region increased over the same period.

There are also new opportunities for economic activity that can help in the context of the Amazon paradox. Here, there are at least four possible paths forward. The first is restoring the original forest, which can be done by planting seedlings of native trees or through allowing abandoned deforested areas to regrow naturally. More than 59 million acres in the Brazilian Amazon are currently deforested and abandoned, not being used for any purpose, and are prime candidates for reforestation.

On the demand side, there’s also a growing market for carbon capture through forest restoration. According to Time magazine, the net-zero commitments of companies worldwide require restoring almost 900 million acres worldwide by 2050.

The second option, as we highlighted in a special issue of AQ in 2021, is increasing exports of products such as açaí, tropical fruits, fish and Brazil nuts that are compatible with the conservation of the forest. The Brazilian Amazon region already produces and exports these products, only in lower quantities (corresponding to less than 0.1% of the global market). The good news is there is already an enormous—and expanding—global market for these products worth more than $160 billion annually.

Another way forward is to pursue the opportunities presented by carbon markets for the parts of the forest that are still standing. A reduction in deforestation, besides being advantageous and strategic for Brazil, can attract new flows of investment to the Brazilian Amazon. One example is the LEAF Coalition, whose approach is to exchange payment for a reduction in emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+) at the national and subnational level. According to LEAF, stopping deforestation in the Amazon by the end of the decade could generate as much as $18.2 billion through carbon markets at a minimum price of $10 per ton of CO2. If prices rise to $15, intake could reach $26 billion.

Making use of already deforested areas

Finally, there are ample opportunities to increase the productivity of agriculture in the Brazilian Amazon. Only 10% of deforested areas are being used at a level equivalent to the productivity of modern Brazilian agribusiness. There is sufficient area in unused and underused deforested areas to satisfy all the demand for the expansion of agribusiness in the region, and also to allow areas to be reforested for paper or cellulose products or for palm oil plantations. We should concentrate efforts in these areas to increase productivity through adoption of agricultural best practices, access to finance, infrastructure improvement and securing land tenure. The greatest potential to generate employment and value in the rural Brazilian Amazon lies precisely in areas that are already deforested.

The chief demand of people who live in the Amazon is for the opportunity to work. To accelerate job growth, we should invest where people already are. Research indicates that the sectors that generate the most jobs are in cities, far from areas of agricultural activity. And the highest-quality jobs, ones that offer the chance for a better standard of living, are also in cities. For this reason, a priority for the direction of public resources should be urban infrastructure.

But there are at least two challenges. One is education—in need of reform throughout Brazil—and professional education in particular. The other is the challenge of ensuring access to markets across the vast distances that the Brazilian Amazon region spans. Technology is one answer to both problems. Improving internet access has proven efficient in promoting gains in income, productivity and employability in other tropical regions.

The Amazon paradox urgently needs to be addressed. To keep the forest intact, the top priority should be to recover or make more productive areas of forest already cut down, while offering quality education and technology to the people for whom the Brazilian Amazon is home—especially young people. These measures are key for the future of the largest and richest tropical forest on Earth.

—

Veríssimo is the co-founder of the Amazon Institute of People and the Environment (Imazon), and director of the Amazon Entrepreneurship Center.

Assunção is associate professor of economics at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro, executive director of the Climate Policy Initiative and co-coordinator, with Veríssimo, of the Amazônia 2030 initiative.