This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on the Summit of the Americas

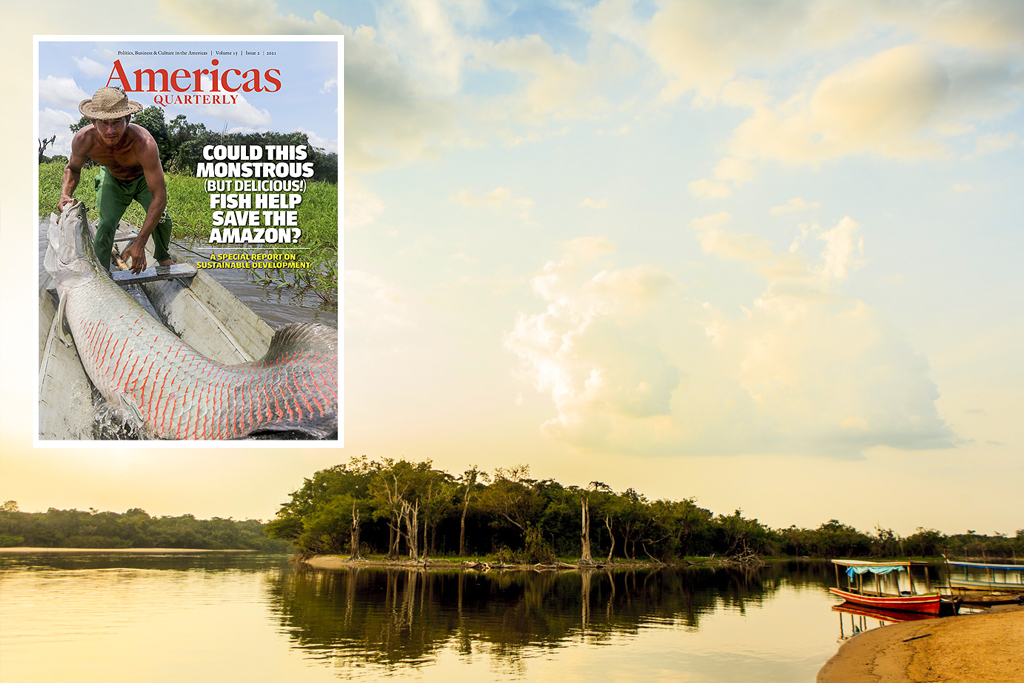

RIO DE JANEIRO – Last May’s special edition of Americas Quarterly on sustainable development in the Amazon showcased the region’s enormous potential for economic growth that simultaneously protects the environment and promotes social well-being. Since the issue was published, the private sector, local politicians and civil society groups have taken massive steps to capitalize on this potential despite the regressive policies of President Jair Bolsonaro and his administration. Now, the fate of this progress may hinge on the outcome of the October general elections.

Numerous positive initiatives are flourishing. The Consortium of Amazon Governors put inequality and illegal deforestation on the regional agenda through its Green Recovery Plan. Pará state strengthened its Amazon Now Plan to tackle environmental crime and constructively regulate green economic activity. The Green Climate Fund, in partnership with the Inter-American Development Bank, approved a $600 million Amazon Bioeconomy Fund, and a coalition of NGOs and companies called the Amazon Concertation launched an initiative to boost sustainable private investment in the region.

These developments demonstrate both public and private sector determination to transform Amazon economies in desperate need of change. In December, the Social Progress Index released its newest report, showing that in the Brazilian Amazon, municipalities with the highest deforestation rates have the worst quality of life indicators. These municipalities rely on economic activities—such as illegal mining and intensive cattle and soy farming—that not only harm the environment but also drive intense inequality and resource concentration.

Development that destroys rainforest also harms some of Brazil’s most disenfranchised and vulnerable people, including the residents of favelas in cities like Manaus and Belém, and the public is increasingly concerned. A survey published last September found that almost 80% of Brazilians think it’s very important to protect the Amazon and that 58% would consider voting for a president who presents a specific plan to do so.

And yet, the Bolsonaro administration has been moving in the opposite direction. Bolsonaro and his allies continue to weaken environmental laws, encourage harmful activity in the Amazon and jeopardize the lands of indigenous and quilombola communities. During COP26, the UN’s 2021 climate change summit, Brazil’s Environment Minister Joaquim Leite announced new climate pledges to calm international criticism of the country’s environmental record. He said Brazil would end illegal deforestation and halve its greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, but these promises were not met with as much skepticism from the international community as might be expected.

The testimony of U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Brian Nichols before the House Foreign Affairs Committee on February 3 is a case in point. Nichols said that during COP26, the U.S. “was able to achieve much stronger commitments from the Brazilian government than anyone would have expected, and they are working hard to implement them.” But there’s no clear sign that the Brazilian government will keep its promises.

Bolsonaro failed to meet the 2020 deforestation goal set out in the National Climate Change Plan, and Amazon deforestation hit an all-time high in 2021. In just the first three weeks of January 2022—as Bolsonaro continued his campaign to expand mining in indigenous territories—an area of rainforest more than six times the size of Manhattan was destroyed, according to the Brazilian National Institute for Space Research (INPE). Meanwhile, much of the Amazon is losing its ability to recover from the destruction as it nears dangerous tipping points; more than half the rainforest could become savanna in just decades, according to a study published on March 8 in the scientific journal Nature Climate Change.

In the October general elections, the public will have a say in the future of the Amazon at a critical moment in the rainforest’s history. Voters will likely face a stark choice between two radically different futures. In one, the Bolsonaro administration’s destructive environmental policies will continue to concentrate wealth and deepen inequality. In the other, new models of more equitable development will protect the environment, create green jobs and put food on the table for Brazilian families. The Amazon will be on the ballot.

—

Hairon is the climate justice program officer for Latin America and the Caribbean at Open Society Foundations