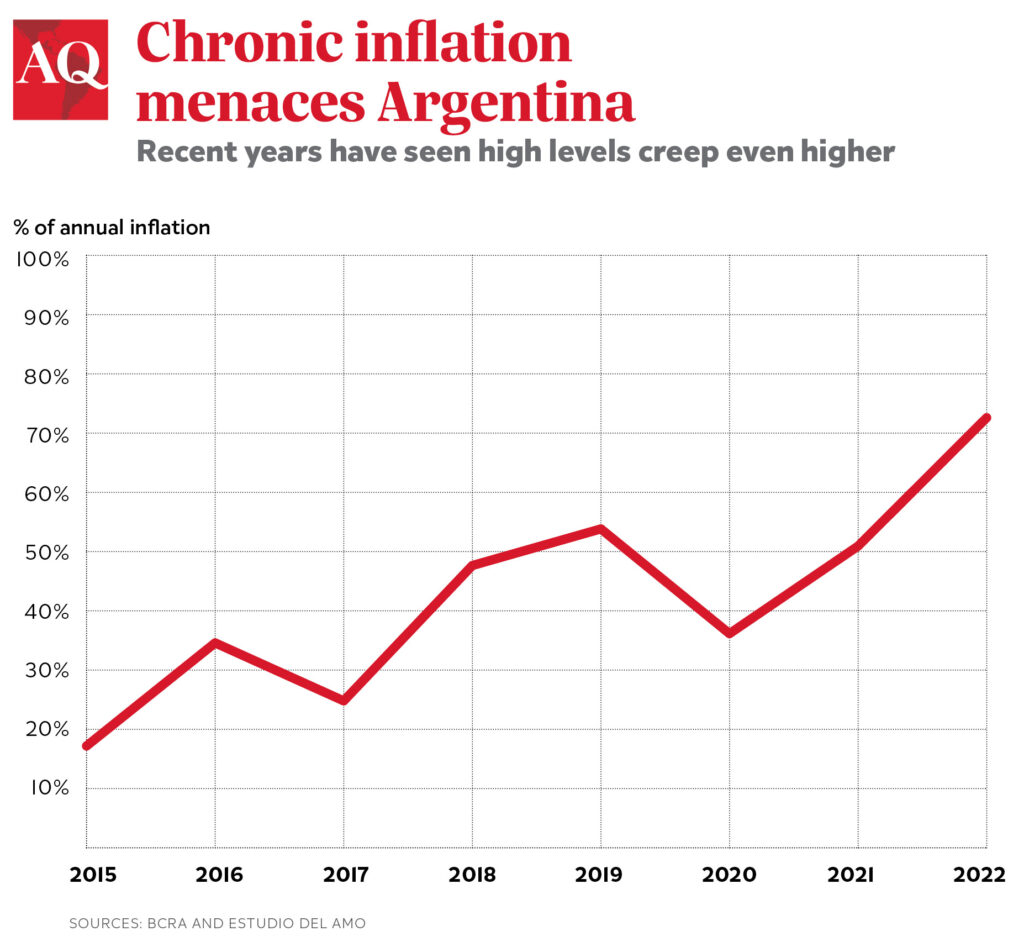

NEUQUÉN, Argentina — It would be an understatement to say that Argentina has a pathological relationship with inflation. Going back to the mid-20th century, hardly any country in the Western Hemisphere has a worse track record. After hyperinflation in 1989, a currency peg during the 1990s held back price increases until they spiked again in 2002—and ever since, inflation has been the country’s main macroeconomic issue. But inflation has not always represented a political problem.

Now it does. Previously running around 50% per year, inflation is set to hit 70% in 2022, presenting a massive challenge for the fractious Peronist coalition led by President Alberto Fernández. With the 2023 elections approaching, outsider figures like libertarian Javier Milei have emerged as contenders, bringing with them ideas for radical solutions to inflation, such as dollarization of the economy. What does inflation have in store for the Argentine government?

The macroeconomic causes of inflation are still debated in Argentina, but its political effects are clear and concrete: They can end the electoral prospects of governments, and even threaten their immediate survival.

But there’s a caveat. Argentine society and its political system can tolerate inflation rates that would cause riots elsewhere. High inflation is electoral kryptonite, but annual rates of 20% or even 30% might be acceptable to the voting public, if activity and real wages are seen to be keeping up. Anything beyond that level can doom the electoral prospects of whoever is in power, even causing a presidential crisis and the fall of the government. But inflation also provides opportunity: If a government can bring the rate down, or even if it is perceived as having done so, this can be a tremendous political boon.

Looking to Argentine history, four possible scenarios emerge for the current government.

Hyperinflation and government failure

Former President Raúl Alfonsín’s trajectory represents the worst-case scenario for the government. Elected in 1983, Alfonsín was met with a wave of enthusiasm as the first democratic president after seven years of the worst dictatorship in Argentina’s history. But he faced daunting constraints: the aftermath of the 1982 debt crisis, heavy foreign debt, high prices and falling wages. His government implemented a stabilization plan called the “Plan Austral” in June 1985, which included a devaluation, the creation of a new currency and price controls.

The Austral plan was a success. It lowered inflation to around 2% per month within its first three months, and Alfonsín rode the ensuing wave of popularity to a victory in midterm elections in November 1985. Encouraged by the electoral results, Alfonsín launched a new political movement with lofty goals. But inflation started to rise again, spiraling out of control in 1988. In 1989, the monthly inflation rate reached a peak of 194% as food shortages and supermarket looting hit several cities. Alfonsín was forced to change the election date from October to June and the opposition candidate, Carlos Menem, won handily.

Political stability with high inflation

Cristina Fernández de Kirchner came to power in 2007, a year with an annual inflation rate of 26%. (The precise rate is hard to know, since the official index was unreliable.) The inflation rate fluctuated during her eight-year tenure, but she was able to keep it from spiraling out of control. Still, inflation was perceived as the number one economic problem of her tenure and was one of the key factors in Mauricio Macri’s victory, after he promised that “bringing down inflation is the simplest thing to do.”

But inflation never threatened the stability of the Cristina Fernández government. This was due to three key elements: high but relatively stable inflation, the fact that real wages more or less kept up, and the creation of new social programs, such as social security benefits for women and a universal child subsidy.

Electoral defeat without political crisis

Mauricio Macri’s government between 2015 and 2019 failed to rein in inflation and paid the price, but without setting off a broader crisis like Alfonsín. Macri’s defeat in his bid for reelection was extraordinarily rare in Argentine politics, which favors incumbents. His central bank set a goal of 10% inflation in 2016, plus or minus 2 percentage points. But the yearly figure was 54% when he left office in 2019, and real wages dropped 20% during his tenure. His inability to control inflation was one of the main causes of his defeat, but he managed to avoid a full-blown crisis.

“Success” on inflation and at the ballot box

For a leader to appear unable to control inflation is political poison—but an apparent victory over inflation is a guarantee of success. Such was the case with Carlos Menem. He was sworn into office right after the hyperinflationary months of 1989. In 1991, Domingo Cavallo, then Menem’s economy minister, came up with a dollar peg for the peso that brought inflation down swiftly. This allowed Menem not only to win reelection in 1995, but to redraw the constitution and implement structural reforms that changed the nature of the Argentine state.

Prospects for the current government

The million-dollar question is which one of the previous trajectories Alberto Fernández’s government will end up taking. Currently, he seems mired in the third scenario, headed towards defeat without a crisis. His party lost the midterm elections of 2021, and polls for next year’s elections do not look good. He has not been able to reduce the very high inflation rate he inherited from Macri; instead, it has spiked in recent months, with a monthly rate of 6.7% in March, though it dropped to 5% in May. If the government is not able to at least stabilize inflation, his electoral prospects are dire.

His opponents argue that his government is moving into the first scenario—full-scale crisis. It’s at least true that the very public disagreements between Alberto Fernández and his vice president slow the government down, throw into question much-needed energy investment projects, and demoralize the coalition.

But his economic cabinet is betting that once the international context stabilizes, and given that Argentina has signed an agreement with the IMF, inflation rates will come down. In that case, he might see his electoral prospects improve. This would move him closer to the fourth scenario—success on inflation and politically.

It is impossible to forecast which of these scenarios is the most probable. In a few months there will be a clearer picture of both the international context and the internal power dynamic heading into 2023. If the slight drop in the inflation rates of April and May can be consolidated, the government will gain some breathing room. If so, it will be competitive in the next elections, if only because Peronism has a loyal base of support. If rates climb again, talks of a crisis will be renewed.

And if things continue as they are now, the government will limp along until the next election, which it will lose. Then, inflation will simply become the main problem for a new government.

—

Casullo is a political scientist and professor at the National University of Río Negro.