This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on cybersecurity

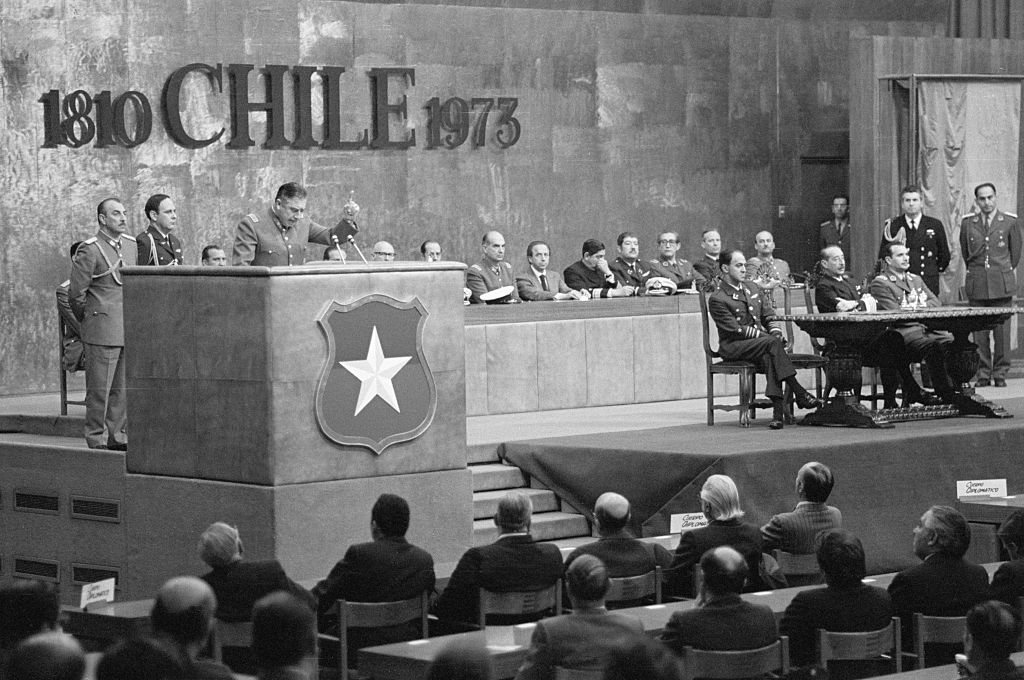

One of the most tragic, murderous chapters in Latin America’s modern history gave rise to arguably its most successful economic experiment. This difficult truth is the subject of Sebastián Edwards’ new book, The Chile Project: The Story of the Chicago Boys and the Downfall of Neoliberalism. As the title suggests, Edwards tries to not only reckon with the legacy of Augusto Pinochet’s 1973 coup, but also connect it to policy debates still raging today in Chile and indeed throughout the Western world. It’s an emotionally charged, fraught task, one at which the book admirably succeeds—with one unfortunate exception.

The Chicago Boys of the book’s title were a shifting group of young Chilean economists, many (though not all) of whom graduated from the University of Chicago and were disciples of the free-market guru Milton Friedman, whose 1975 visit to Santiago seems to have decisively convinced Pinochet to put the “boys” in charge of the economy. It is fascinating, and revealing about today’s politics in Chile and elsewhere, that none of the Chicago Boys whom Edwards interviewed for his book self-identifies today as a “neoliberal,” describing their project as more socially minded than critics believed. But, terminology aside, there is no doubt that their agenda of privatizations, tariff cuts, deregulation and overall embrace of a business-friendly, free-trading model was unlike anything that had ever been tried in Latin America before.

That they did this during an era when Chilean dissidents were still being machine-gunned and thrown from helicopters into the sea is a stain that continues to haunt—and delegitimize—Latin American capitalism today. Early in the book, Edwards acknowledges the obvious: “Given the historical moment,” he writes, “a neoliberal revolution of this magnitude could not have been possible under a democratic regime.” That doesn’t mean the reformers always had it easy: Nationalist sectors of Chile’s military strongly resisted their efforts, suspecting they were giving away the country’s wealth to nefarious foreign interests; the notorious DINA secret police even ordered them followed. But there’s no doubt the Pinochet regime’s repression permitted “shock therapy,” holding the line even as unemployment soared beyond 25%, waiting for a more dynamic and sustainable economy to take root.

That payoff did eventually come—and how. Today’s Chile has a per capita income double that of Ecuador, and 40% higher than Costa Rica; the three countries were peers in the 1980s. Far from being “just” a story of GDP growth, or only the rich getting richer, Chile also has Latin America’s highest human development indices, and its second-lowest poverty rate, behind Uruguay. Much of this progress happened after democracy returned in 1990, but few disagree that the Chicago Boys’ policies laid the groundwork.

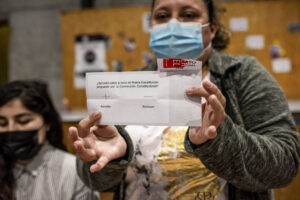

Of course, Edwards’ book comes out at a time when that legacy is being questioned; he is laudably direct and honest about flaws in the Chilean model, namely persistently severe inequality, that led to the 2019 protests and their (now uncertain) aftermath. Which is why it is such a disappointment that the author waits until the very end of his section on the Pinochet years to ask, “Did the Chicago Boys know about human rights violations?” and then dedicates barely three pages to the answer, lamely concluding: “We will never know for sure the facts on these thorny issues.” This is not just a matter of historical record; the question of whether and how Latin America’s economies can be effectively reformed under democracy is as relevant as ever in today’s context of stagnation and renewed social unrest. Edwards’ book suggests, in both its brilliance and its shortcomings, that the answer remains sadly elusive.