QUITO — On February 9, Ecuadorians will head to the polls for consequential presidential and legislative elections for the third time in four years, against a backdrop of unprecedented challenges.

The contests come at a critical juncture for the nation’s fragile democracy, battered economy, and embattled society. President Daniel Noboa has had only a brief term in office; he came to power in 2023 as an outsider candidate after then-President Guillermo Lasso called snap presidential and legislative elections. Noboa is now running for reelection with the Acción Democrática Nacional (ADN) party.

Ecuador faces a surge in criminal violence that has, in just a few years, turned the country into one of the deadliest nations in the hemisphere as Ecuadorian gangs, alongside Colombian, Mexican, and Albanian crime groups, battle to control an expanding cocaine trade and its overseas routes. Meanwhile, Ecuador’s economy has contracted on a per capita basis for over five years, stagnating standards of living and driving thousands to migrate to the U.S.

Compounding these crises, most state institutions are in disarray—and widely delegitimized—following a failed multi-year effort to dismantle the socialist correísta political order that dominated Ecuador from 2009 to 2019. Public frustration with the current state of affairs is palpable, with over 70% of voters expressing dissatisfaction with the country’s situation. This has created a volatile environment ripe for surprises.

A two-horse race

Ecuador’s presidential contest features a large pool of 16 candidates, a phenomenon driven by the state-subsidized election process. In Ecuador’s system, the government covers campaign advertising costs for all qualifying candidates, lowering the barrier to entry and incentivizing a wide range of individuals and parties to participate. This extensive field spans the entire political spectrum, from the radical left to the far right.

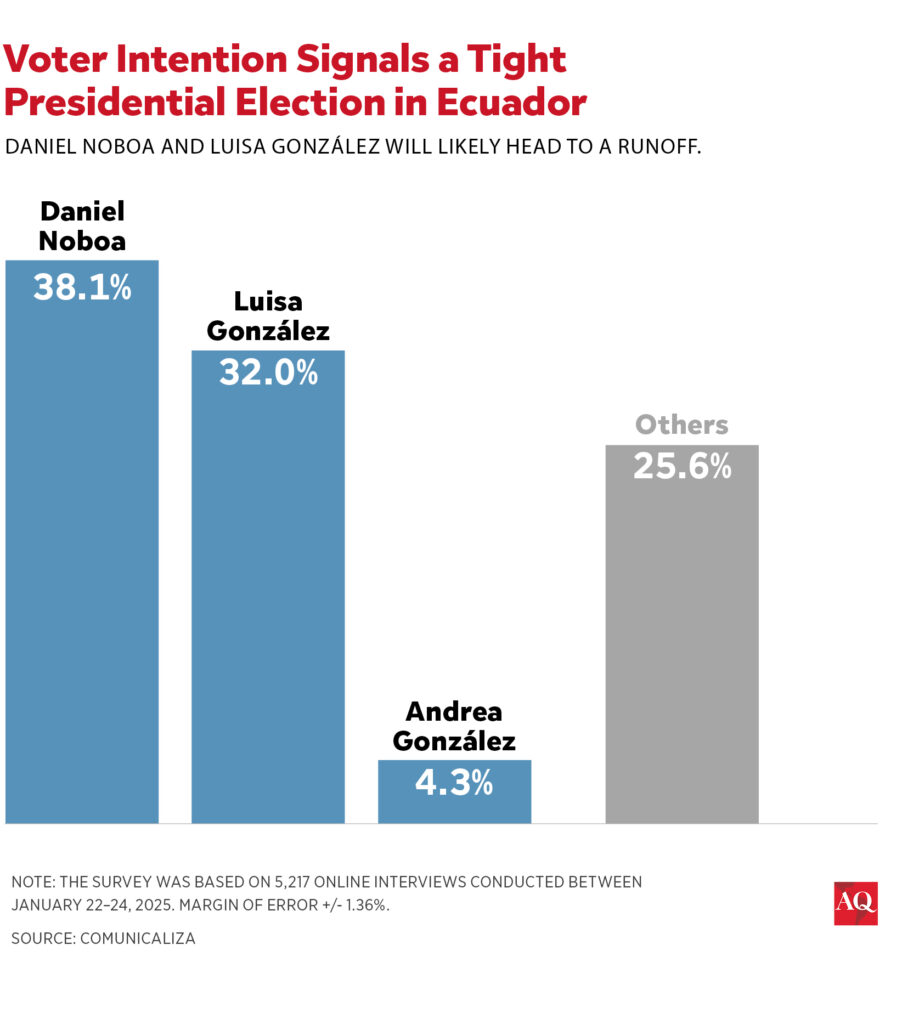

Despite the crowded field, the presidential election is shaping up to be a two-horse race between the incumbent President Noboa and Luisa González, the correísta candidate of Revolución Ciudadana, the political party of former President Rafael Correa. Credible polls consistently show both leading the pack, with Noboa garnering 36–40% of first-round support and González close behind at 32–36%. The remaining candidates poll below 4%, with most hovering near zero.

At just 37 years old, Noboa remains one of Ecuador’s most popular political figures, enjoying a 40-50% approval rating. His appeal lies in his image as a youthful political outsider untainted by what he refers to as the “old political class,” as well as his reputation as a decisive fighter against organized crime. Though his year-long “war” on crime has only modestly reduced homicides by 16% compared to a record-high 2023, many see it as progress on voters’ top concern: public security.

Noboa has also actively leveraged the executive branch’s powers to offset his lack of a strong party structure, distributing targeted subsidies and benefits during campaign season. Critics accuse him of exploiting judicial and electoral authorities to weaken political opponents, raising questions about democratic integrity. Verónica Abad, the vice president and former running mate, even accused him of “taking power by force.”

Apart from former President Rafael Correa, who won multiple consecutive elections, no incumbent president in recent Ecuadorian history besides Noboa has stood a chance of being reelected. However, he remains vulnerable to unforeseen events, such as a major security failure or unexpected crises like last year’s energy blackouts, which temporarily dented his support. For example, despite the war on organized crime declared a year ago by Noboa’s administration, the month of January 2025 is set to become the deadliest ever just ahead of the election.

Luisa González, for her part, benefits from Correa’s enduring popularity. After Noboa, Correa is Ecuador’s most popular political figure. Backed by a highly organized correísta party apparatus, González has positioned herself as an alternative to recent administrations’ “neoliberal” policies. Her campaign emphasizes a return to the perceived stability and achievements of correísmo, such as low crime and major public works projects.

However, the legacy of corruption scandals and alignment with controversial figures, like imprisoned former Vice President Jorge Glas and Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro, cast a long shadow and provide her opponents ample opportunities for political attacks. For example, President Noboa recently invited top regional government officials from correísmo to meet for lunch in Quito with Venezuela’s “rightful president-in-exile,” Edmundo González, in a veiled effort to expose their ambivalent position toward that country’s dictatorship.

What to expect

While a first-round victory remains possible if the leading candidate obtains over 50% of valid votes, or at least 40% plus a 10% difference with the runner-up, a runoff between Noboa and González is the most likely scenario, with current polling favoring Noboa in the second round.

The expected trajectories of policy under Noboa and González diverge sharply. A Noboa administration would likely pursue pro-business reforms, continue efforts to attract foreign investment, and strengthen ties with the IMF and multilateral organizations. It would also take an increasingly aggressive approach to fighting crime in cooperation with foreign governments, particularly the U.S.

In contrast, a González administration would prioritize reinstating the “correísta political order” to handle political, economic, and security challenges more effectively. She would likely emphasize redistributive policies, state-led economic initiatives, negotiation with specific violent groups, regional alliances with leftist governments, and global alignment with BRICS nations.

A cooperative legislature

Equally significant are the legislative elections, as Ecuador’s persistent political instability has been fueled by executive-legislative deadlock.

The correísta Revolución Ciudadana (RC) movement is likely to retain the largest bloc in the National Assembly, securing around 40% of seats. Noboa’s Acción Democrática Nacional (ADN) party could achieve a historic breakthrough with around 35% of seats, making it the first time in over 15 years that a political party other than correísmo has wielded such significant influence. Other traditional parties represented in today’s National Assembly, like PSC, Construye and Pachakutik, are likely to see their representation wane or remain marginal.

While neither Noboa nor González will enjoy an outright majority in the National Assembly, having the largest bloc would provide either with enough political leverage to build a governing coalition with smaller parties. This will not only provide political stability to the new administration to be inaugurated in May, but also momentum for much-needed economic reforms, which are crucial to reignite growth.

Governability should be the key factor to watch in Ecuador, which urgently needs a stable, reform-oriented government capable of staying in power for an entire presidential period and delivering reforms. Failure to achieve this could deepen Ecuador’s multiple crises, leaving a frustrated citizenry and an even more fragile democracy in its wake.