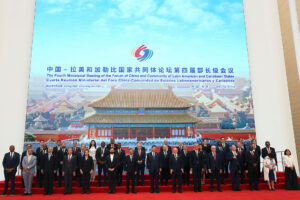

BOGOTÁ—In May, Colombia made two consequential foreign policy moves aimed at ramping up its engagement with China. As President Gustavo Petro visited Beijing last month for the China-CELAC Forum, his administration announced that Colombia had joined the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s signature development program. Just a few days later, the Petro government applied to join the BRICS’ New Development Bank, and was accepted on June 19.

Compared to other South American nations, Colombia’s pivot to China is recent and reflects a reactive approach to foreign policy. Brazil’s longstanding and intensifying cooperation with Beijing will be on full display at the BRICS Summit in Rio de Janeiro on July 6-7. Chile signed a free-trade agreement with China two decades ago, demonstrating the benefits of forward-thinking trade diplomacy.

It was not pragmatic planning but rather the Trump administration’s announcement of tariff rates not seen since the Smoot-Hawley era that finally prompted Colombia toward closer engagement with China, despite strong warnings from Washington. While this membership carries no immediate legal obligations, it is a significant political statement in an evolving geopolitical landscape where the U.S. pursues an “America First” agenda aimed at reducing its trade deficit.

The timing of this decision could hardly be worse, and exemplifies Colombia’s lack of long-term strategic planning in foreign affairs. Instead of proactively developing a comprehensive strategy to engage multiple trading partners and diversify export destinations, as I outlined four years ago in these pages, Colombia has adopted a reactive approach to shifting international dynamics. However, there are still paths that current and future administrations can pursue to navigate U.S.-China tensions while expanding trade.

What’s at stake for U.S. relations

Colombia’s Belt and Road membership will likely provide additional justification for the U.S. to decertify the country regarding anti-narcotics efforts—an area where performance has been abysmal. According to the UN’s SIMCI report, coca cultivation increased by 10% from 2022 to 2023, while potential cocaine production rose by a staggering 53%—a productivity success story, unfortunately, in the wrong sector. Over the past decade, coca cultivation has increased fivefold. Against this backdrop, Colombia’s joining of the BRI risks further damaging its standing with its most important ally.

However, Washington will likely refrain from imposing additional punitive measures on Colombia. Aggressive action could push Colombia further into China’s sphere of influence, directly contradicting U.S. strategic interests. Moreover, with President Petro’s term ending in just 14 months and elections scheduled for no later than June 2026, the Trump administration will probably adopt a wait-and-see approach, preferring to engage with a new Colombian government. Consequently, damage to U.S.-Colombia relations should remain contained in the short term.

Colombia-China ties

Colombia’s growing ties with China are most visible in trade and investment. Total trade between the two countries rose from $1.2 billion in 2004 to $18.3 billion in 2024—a fifteenfold increase. Over the same period, trade with the U.S. also expanded, rising to $30.8 billion. Out of a total of $49.6 billion in exports, Colombia exports $14.3 billion to the U.S., compared to just $2.4 billion to China.

In terms of investment, Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in Colombia grew from negligible levels to around $580 million over the past three years. However, this figure is still far below U.S. FDI, which reached $16.1 billion during the same period.

Project financing has been another important area of engagement. Between 2018 and 2023, Chinese development and commercial banks—primarily the China Development Bank and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China—financed approximately $1.4 billion in projects in Colombia. The infrastructure sector received the lion’s share—over 80% of the total—followed by energy, manufacturing and mining. Major projects include the Autopista al Mar 2 ($417.7 million), the first line of the Bogotá Metro ($230 million), and the expansion of El Dorado Airport ($175 million). These initiatives reflect China’s growing role in financing and executing strategic infrastructure and energy developments in Colombia.

Against this backdrop, President Petro’s decision to join the Belt and Road Initiative is aimed at “reducing Colombia’s $14 billion trade deficit with China” and boosting exports to up to $10 billion, including products such as shrimp, tuna, coconut, cacao and coffee. Additionally, in announcing Colombia’s acceptance into the New Development Bank, the Petro administration emphasized the potential to improve access to financing for the energy transition, regional connectivity, and other structural priorities.

A strategy for moving forward

What should Colombia’s current and next governments do?

First, the country must dramatically expand its access to global markets in order to increase exports, which today total only around $1,000 per capita—far below the OECD average of $13,500. While Colombia has signed numerous free trade agreements, including with the U.S., it needs to make much greater use of them.

The challenge lies not only in exporting more of what Colombia already produces—oil and carbon account for 45% of total exports—but also in identifying new, higher value-added goods and services that allow the country to integrate into global value chains and seize the opportunities offered by nearshoring and friendshoring.

Second, Colombia should broaden its focus from China specifically to Asia more generally. Trade ties with Asia remain limited in scope and depth compared to the country’s agreements with the Americas and Europe. The 2016 free trade agreement with South Korea was a positive step, but it must be followed by renewed efforts to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which includes major Asian economies such as Japan, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam. The CPTPP’s Latin American members are Chile, Mexico and Peru, Colombia’s fellow members in the Pacific Alliance bloc.

Broadening trade engagement across Asia would accomplish two critical objectives: It would offer strategic direction to Colombia’s trade policy, while raising fewer concerns in Washington. Despite current tensions, Colombia should continue opening its borders and accessing new markets to accelerate technology adoption, enhance productivity, and stimulate economic growth.

Colombia stands at a crossroads. It must move beyond reactive diplomacy and adopt a coherent, long-term strategy that maximizes its economic potential while skillfully navigating great power competition. The alternative—continued ad hoc responses to shifting external pressures—will only limit Colombia’s options and undermine its long-term development.