This article is part of a series examining the evolving relationships between China and Latin America.

BOGOTÁ – It’s been said a lot over the past 20 years, but it remains true today: Colombia is one of the closest allies and strategic partners of the United States in Latin America.

Decades of bipartisan support from the U.S. have resulted in billions of dollars invested through many programs including Plan Colombia, as well as more recent initiatives that have supported the implementation of the peace accord with the FARC and have helped cope with the nearly 1.8 million Venezuelan migrants currently living in Colombia. The U.S. is also Colombia’s main trading and investment partner, leveraged by preferential access through the U.S.-Colombia free trade agreement signed in 2012. The combined value of exports and imports of goods between the two countries averaged $27.6 billion per year for the past decade.

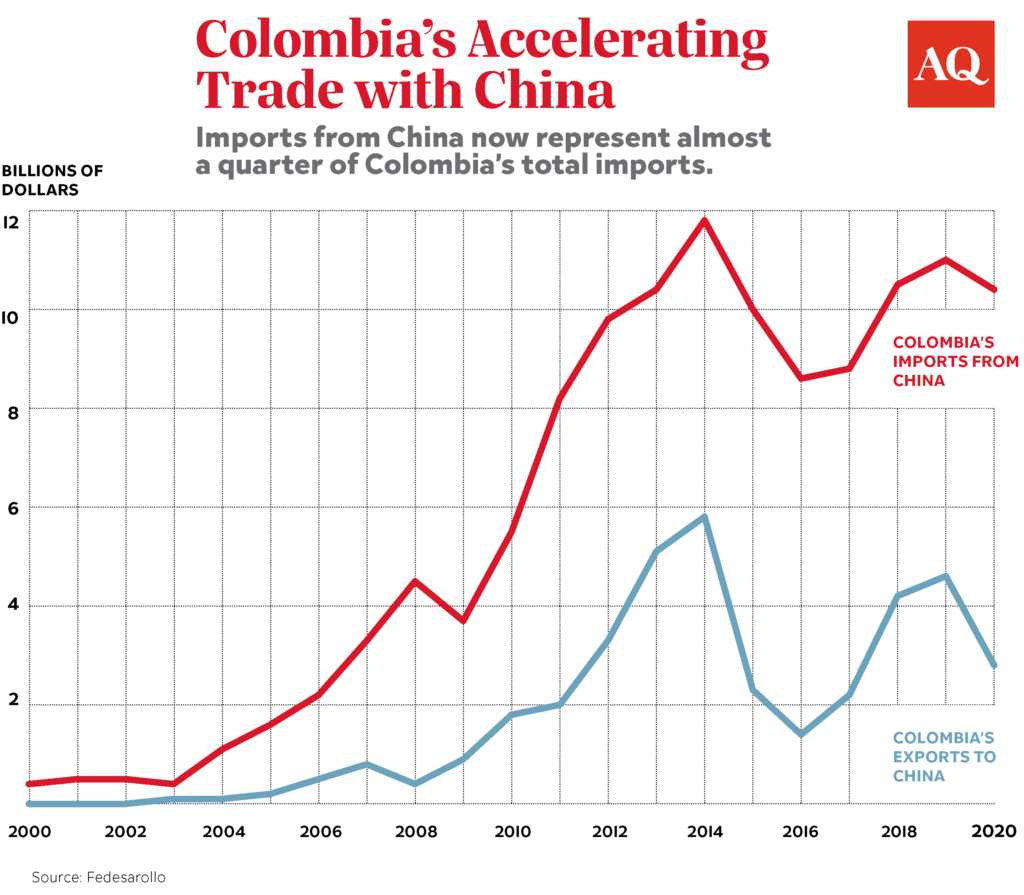

As recently as 10 years ago, things were completely different with China, the U.S.’ main rival for global power. Colombia exported on average a mere half a billion dollars per annum to China in the first decade of the 21th century, while importing about $2.3 billion. China was ranked 37th in terms of importance as a destination of Colombia’s exports in 2000. But these numbers have changed at an accelerated pace for the past decade. China is now Colombia’s second most important trading partner, with average annual exports between 2011 and 2020 ($3.4 billion per year) almost seven times as large as those in the prior decade. Imports of $9.9 billion, meanwhile, now represent almost a quarter of Colombia’s total imports.

The growing importance of Colombia and China’s trade links was particularly valuable during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although Colombia has been the largest recipient of vaccine donations from the U.S., receiving 6 million doses out of the 38 million donated by the U.S. government, the early arrival of Sinovac vaccines during February and March “saved the day” by preventing thousands of deaths among the elderly. Indeed, by the end of March Colombia had received 3.5 million doses, of which 2.5 million came from China. In this sense, U.S. vaccine diplomacy to Colombia was generous, but China came first when it most mattered.

In terms of investment, China has had a relatively small presence in Colombia, especially compared with some of its neighbors, like Ecuador and Venezuela. The largest investment from China came last year with $64 million, which amounts for less than 1% of total net foreign direct investment. But, again, things appear poised to change rapidly. Chinese companies have made investment commitments of more than $6 billion, including the construction of Bogotá’s first metro line, the largest civil works project in the country for the next years, as well as the construction of a tram line in the Bogotá metropolitan region. There are also investments in the mining and energy sector, with prospects for further investments in the coming years.

The U.S.-China conundrum

These trends now threaten to put Colombia, as well as many other Latin American countries, in an uncomfortable position. Given the recent deterioration in Sino-American relations and its implications for global geopolitics, many are asking: Should Colombia further strengthen its ties with the U.S., or continue advancing its rapid pace of trade and investment integration with China?

Barring a full-scale military confrontation, which would force the country to “choose sides,” Colombia should continue to do both. The U.S. has been and will continue to be a strong partner and will act strategically to counterbalance China’s increasing influence in the region. To this end, the U.S. has led the recent launch of the Build Back Better World initiative to help close the $40 trillion infrastructure gap in the developing world, aimed squarely at rivaling China’s own Belt and Road Initiative, adopted in 2013. Colombia should quickly tap into this opportunity and secure funds for infrastructure, climate, health, and digital technology investments, among others.

On the Chinese front, Colombia should follow the example of some countries in the region like Chile and Peru and evaluate the possibility of joining the Belt and Road Initiative. As well, following the example of strong U.S. allies like Australia and the United Kingdom, the country should seriously consider joining the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, a $100 billion multilateral development bank led by China that could also provide much needed cheap capital for narrowing investment gaps in infrastructure and sustainable development. Although these moves could raise some eyebrows among U.S. government officials, the limited availability of cheap financing, especially in a world of higher interest rates as rich countries retire monetary policy stimuli, makes a very compelling argument for increasing and diversifying future sources of finance.

Things are a little more complicated on the trade front. On the exports side, there are still gains to be had, as exports to China ($2.8 billion in 2020) are less than a third than those to the U.S. ($8.9 billion). On the imports side, however, the numbers are about the same ($10.5 billion in 2020). One worry is that China has still not achieved a market-economy status according to the World Trade Organization. It is one thing to deepen competition in domestic markets by opening your borders to imports at market-determined prices, and another completely different to do it at government-subsidized prices at which local producers are unable to compete. Colombia should then carefully monitor imports from China, strengthening trade-observing institutions and acting swiftly to protect local producers from unfair trade practices.

What the future holds…

It is still too early to tell whether China will join the U.S. in the global landscape as the second superpower. Elections in Colombia in 2022 also raise the prospect of a shift in foreign policy, should an anti-establishment figure win. What is certain though, is the extent of China’s growing economic, technological, and political influence in the world, as well as in the Latin American region. The new government will have to carefully balance its approach to both countries, by bolstering its relationship with the U.S, its more important ally, but at the same time reaping the benefits of further trade and investment ties, in a market-oriented framework, with a country like China, that due to its growing size and middle class constitutes an immense opportunity for Colombia.

—

Mejía is the executive director of Fedesarrollo. He was deputy minister and minister of planning of Colombia from 2014-2018, leading the ministry in its implementation of the sustainable development goals agenda. He has also held positions as director for macroeconomic policy at Colombia’s ministry of finance, as well as researcher at Colombia’s central bank and the Inter-American Development Bank in Washington. Follow him on Twitter @LuisFerMejia