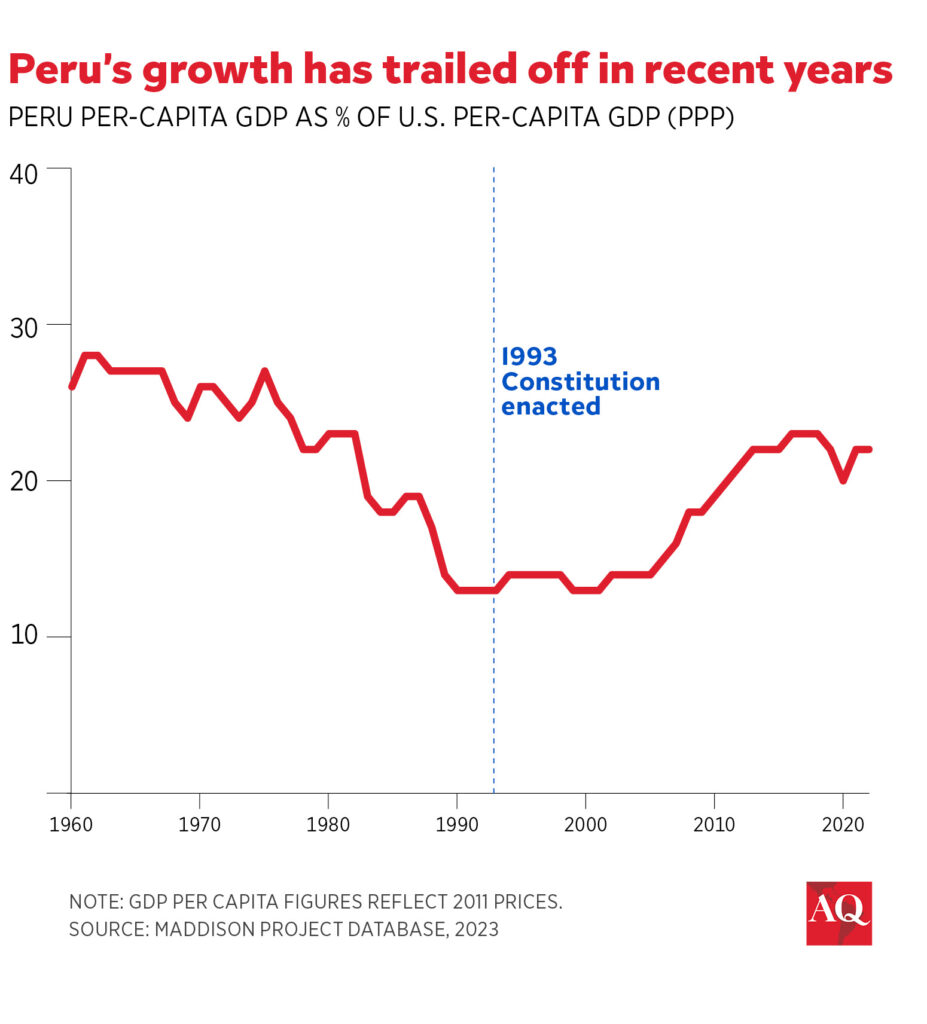

LIMA – Many predicted that politics wasn’t going to compromise Peru’s growth performance, until it did. After Peru spent more than a decade as Latin America’s star economic performer, with average per-capita growth of 5% from 2001 to 2013, a political crisis that started in 2016 has resulted in seven presidents over a period lasting just two full-length presidential terms, as growth has stalled. Even harder to understand is the recent turn that Peruvian politics has taken, departing further and further from public opinion and generating a generalized distrust of democracy.

With Peru now benefiting economically from what looks like a new copper super-cycle, and from its bid to become a port hub overlooking the Pacific, some are wondering whether economic overperformance can once again move politics to the back seat and set the stage for a period of economic and political reforms, as happened in the early 2000s. Is that really possible?

Another unexpected political turn

President Dina Boluarte is currently facing a fresh political crisis, with a third impeachment bid and a coming constitutional accusation from the attorney general’s office. For now, the right-wing majority is backing her, but as the 2026 elections draw nearer, lawmakers will be tempted to look after their own survival and turn their back on her.

Meanwhile, the right and left in Congress have joined forces to seek to re-write the constitution that former President Alberto Fujimori (1990-2000) drafted in the 1990s, seeking to transfer some of the strong powers the 1992 constitution granted to the president to Congress, though without turning Peru into a parliamentary system. Efforts are also being made to overturn reforms regarding the rule of law, education and labor, fiscal discipline, and more recently, on meritocracy in the civil service. These actions undermine the role that the current constitution has had in inducing rapid growth. Also concerning has been Congress’s decision to fill key democratic institutions with loyal civil servants, undermining the checks and balances needed in a democracy.

The copper super-cycle, the port, and China

But the copper super-cycle and the upcoming inauguration of eight ports overlooking the Pacific—including the port of Chancay, built by Chinese-owned Cosco Shipping Ports Ltd and Peru’s Volcan S.A., a mining company—may prove a blessing, despite concerns that it gives the impression that Peru is partnering with China and distancing itself from the U.S.

Starting in 2004, and after a long period of political confrontation, Peru also benefited from high commodity prices and managed to sustain a period of rapid growth, undertake structural reforms and mute political confrontations. Can this happen again?

Being a commodity-based economy with the second-largest copper reserves in the world after Chile and one of the lowest costs of extraction, Peru should benefit at large from the current commodity price boom. Our estimates indicate that 60% of real GDP variance is explained by commodity price cycles. The Ministry of Mining has identified about $55 billion in mining projects (about 20% of GDP), of which only $5 billion are being developed in the next two years, but if the super-cycle can induce the development of these projects, the economy can grow at rapid rates. That these projects are in poor areas—lacking access to public services, roads or other infrastructure—opens the opportunity for the government to benefit the population in these areas and reduce the conflict between the provinces and Lima that resulted in former President Pedro Castillo’s election.

To induce this virtuous circle three things need to happen that in the past have faced strong political resistance. A new profit-sharing agreement between miners and communities must be struck. The government needs to implement a simplification reform granting fast-track approval to most of these mining projects. And there needs to be an effort at formalizing the large number of informal or illegal miners that create unfair competition—and contaminate rivers and the Amazon.

That this is happening at a time when Peru may turn into a port hub in the Pacific may gain the country a unique opportunity and prompt Southern Cone nearshoring. Most attention has been focused on the $3.5 billion Chancay port and China’s investing heavily in Peru in many sectors. It has been argued that the new port could serve China’s military objectives and that Peru could turn into China’s satellite country. That President Boluarte is due to visit China in June and China’s President Xi Jinping has confirmed his visit to Peru in November to inaugurate the new port adds to the speculation.

According to official information, Peru shipped 3 million TEUs (twenty-foot equivalent unit containers) in 2023, 88% of which were shipped out of Callao’s two ports. With the new Callao ports, that should rise to 5.6 million, surpassing other regional ports like Mexico’s Manzanillo and Panama’s Balboa.

To take full advantage of the logistics around these ports, the government is proposing a free economic zone (FEZ) between Chancay and Callao, integrating the Chancay port with the two Callao ports and the new Callao airport. This should result in new infrastructure linking these ports and the airport, some developed by the government, some by the private sector.

With these developments, Peru could turn into a port hub in the Pacific, attracting shipping from neighboring countries such as Chile, Ecuador and Colombia. Even Brazil has indicated its desire to take advantage of Peru’s strategic position and use these ports to reduce transport time to Asia.

The U.S. has sent several high-level officials to enquire why Peru has tended to favor China. Peru’s policymakers have been pragmatic in their foreign relations with China—their top trade partner—and the port development allows them to capture Asia-Latin America trade. The real surprise is that the U.S., a preferred trading partner and one with shared values with Peru, has not invested in similar developments.

While China could benefit by ensuring the commodity supply needed for their industries, the real benefit for Peru is to induce the relocation to Peru of Asian industries that export into the U.S.—targeting high-tech Asian firms, suppliers of U.S. high-tech companies, that find relocating to the U.S. expensive and may benefit from Peru’s trade openness and large number of free trade agreements.

Can economic overperformance mute politics?

The deinstitutionalization and undermining of the 1992 constitution are a handicap and will make it more difficult to restart the rapid growth of the 2000s. But it’s also clear that Peru had periods of overperformance even before the 1992 constitution. The truth is that it’s rare for Peru to face such a favorable external environment as right now. Long-term investors, such as those in mining and infrastructure, heavily discount political instability. If Peru elects a reasonable government in 2026, the economy could move forward and set politics aside. It looks like the country will soon have one more chance to confront its social backwardness and dysfunctional politics.

Subscribe to the Americas Quarterly Podcast on Apple, Spotify and other platforms