BELÉM — Ricardo Salles, Brazil’s environmental minister, made international headlines this week for his public request for foreign aid for the Amazon. Less publicized than Salles’ remarks are two bills currently making their way through Brazil’s Congress that may maintain, and even propel, a devastating trend in deforestation.

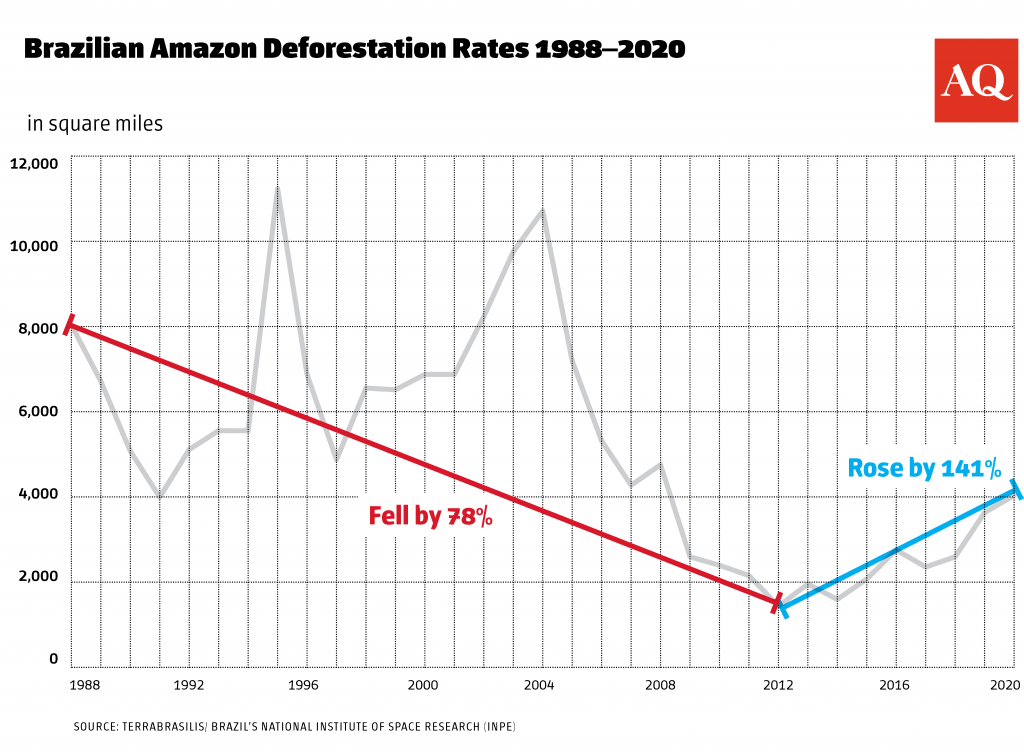

Though Brazil received widespread praise for its conservation efforts not long ago — the country reduced deforestation rates by 80% between 2004 and 2012 — it has progressively lost its environmental reputation. Environmental destruction has surged under the administration of Jair Bolsonaro: Between 2019 and 2020, the Amazon lost 8,192 square miles to deforestation, an area the size of El Salvador.

One of the main causes of this deforestation has been grilagem, a land grabbing practice involving the occupation of public lands and subsequent land clearing. Then, invaders usually plant grass to raise cattle, which is a relatively cheap way to signal land use, and request land titles from the government, turning to Congress’s rural caucus for extensions if their request does not fall within the timeframe of federal registration deadlines.

The two “land grabber bills” (“land regularization bills” to their backers) currently on the floors of the House (PL 2633) and Senate (PL 510), promise to exacerbate an ongoing problem. If passed, they would ease criteria for privatizing public lands that have been illegally deforested, granting, in other words, legal titles to the areas land grabbers occupy.

Proponents of the legislation — both on the regional and federal level — argue that, rather than land grabbing, it is the lack of a formal tenure definition over a wide span of land that has driven the area’s staggering deforestation. Of the region’s 2 million square miles, 50% is public land already designated, primarily as protected areas, and 21.5% is private property. The other 28.5% (an area larger than California and Texas together) is public land with no official designation. It is this area that accounts for 40% of the region’s deforestation each year.

Backers claim the uncertainty over land ownership in this area makes it impossible to punish environmental criminals, ignoring the fact that these are, in fact, public lands (as in, under the purview of either federal or state governments) and prime targets for illegal land grabbers. Allowing for the privatization of such lands post-occupation would thus reward those who commit illegal deforestation rather than punishing them. The incentive for would-be land grabbers is clear as day.

Moreover, in two thirds of deforested areas, it is indeed possible to identify and punish environmental criminals, according to MapBiomas, a collaborative network of Brazilian NGOs and universities. In the other one third of the deforested area — where landholders’ identification does not exist — environmental agencies can use deforestation data from Brazil’s National Space Research Institute (INPE), disclosed in near real-time, to guide field enforcement inspections, a tool that proved crucial in the deforestation reduction of 2004-2012.

It is true that existing land regulation laws are problematic, but they are problematic in favor of land grabbers. Under most existing state laws, public lands occupied and deforested now or even in the future may be vulnerable to privatization, as there is no land occupation deadline for titling. This is the case in Amazonas, where the state government is responsible for 29% of the undesignated land in the region, and in four other states in the Amazon (Acre, Maranhão, Mato Grosso and Tocantins). Also, no state law prohibits the titling of areas predominantly covered by public forests (i.e. 90% of forests). In such cases, after receiving a land title, new owners may request authorization to legally deforest up to 20% of their property.

Put simply, supporting the current model of land regularization, or changing the laws to make land privatization even easier, will inevitably result in more illegal occupations and deforestation of public land in the coming years.

To stop this destructive cycle, Brazil needs to start by enforcing its constitution that determines indigenous land demarcations should take precedence over privatization. But this is a tenet the Bolsonaro government intentionally ignores, even if various scientific studies have identified indigenous territories’ demarcation as the best policy to conserve forests. Also, 43% of non-designated public land in the Amazon region holds conservation priority and can be transformed into protected areas. The government can also use concessions to allocate public areas to enterprises engaged in sustainable logging.

It is true that there is great demand for land privatization. According to Incra, Brazil’s federal land agency, 170,000 families are currently requesting land titles in the region. The existing laws allow for such land rights recognition in areas without other priority land claims or conservation interests, but we must align regularization demands with forest protection laws.

Any reasonable attempt to improve land laws must have at least three elements: one, a clear deadline for public land occupation eligible for titles (for states without such a time limit); two, the inclusion of a clause in state and federal constitutions to prohibit deadline changes; and three, a ban on the privatization of recently deforested lands.

The bills currently sitting in Congress and any other proposals to revise land laws without these elements will inevitably favor land grabbers, deepening an already vicious cycle of land invasion and deforestation. It is now up to Congress to recognize this and break the cycle before it is too late.

—

Brito is an associate researcher at Imazon. She coordinated the recently launched report Ten Essential Facts about Land Regularization in the Brazilian Amazon.