This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on the education crisis

In certain Brazilian circles, the rewriting of history has already begun: Jair Bolsonaro’s 2018 election victory was an aberration, an accident, the product of a now-discredited corruption investigation that unfairly put the rightful winner, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, in jail. Now free, Lula is leading Bolsonaro in polls for this October’s election by 10–20 points or more. As the thinking goes, the fever of the last four years will soon break, and Brazil will return to its normal left-of-center point of equilibrium.

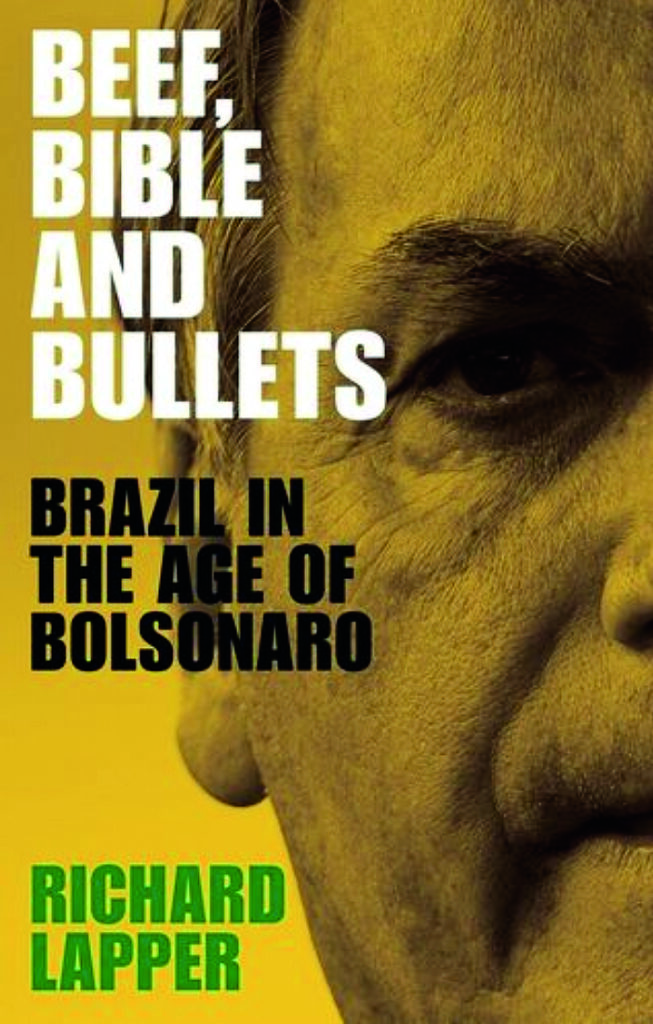

Richard Lapper’s book Beef, Bible and Bullets: Brazil in the Age of Bolsonaro is a powerful counterargument, full of richly reported stories and data showing the country’s conservative movement is here to stay, even if its now profoundly unpopular leader ends up being shoved aside. The book’s title refers to the bloc of legislators in Congress representing, respectively, Brazil’s agribusiness, evangelical Christians and gun lobbies—all of which have enormously expanded their numbers and influence in the past 30 years. Even for specialists, some of the details here are eye-popping.

Beef, Bible and Bullets: Brazil in the Age of Bolsonaro

by Richard Lapper

Manchester University Press

Hardcover

272 pages

Lapper starts with a fresh look back at what conservatives originally rebelled against—the Brazil left behind by 14 years of Workers’ Party (PT) rule. The problems of that era are well-known: The worst recession in Brazil’s history, endemic graft, and a years-long rise in crime that, by 2016, made 68% of Brazilians say in polls they almost constantly feared becoming a victim of violence, more than double the percentage of Mexicans who said the same. Meanwhile, the Brazilian state expanded to reach a bloated 38% of GDP, much larger than peers like Mexico (26%) and Chile (25%) and even bigger than China (34%) and Russia (33%), crowding out the private sector and acting as a clear brake on long-term economic growth.

All this explains the “liberal-conservative” alliance of business leaders, gun-toting anti-crime types and social conservatives that began to take shape even before Bolsonaro’s election. The growth of the evangelical community, from 6% of Brazil’s population in 1980 to an estimated 31% today, has radically and perhaps permanently changed what Brazilians want from their politicians. One of the best passages of the book involves a group of preachers in a favela in Uberlândia, in Minas Gerais state, who had repeatedly voted PT prior to 2018. But the party’s emphasis on gender and LGBTQ rights alienated many. One plaintively told Lapper: “God showed me that I should vote for Bolsonaro.”

The truth of course is that Bolsonaro has delivered, at best, mixed results to these constituents. Homicides are down (for a variety of reasons), and evangelicals have gained a greater voice on issues like education, plus a seat on the Supreme Court. But COVID-19 exacted a brutal toll, numerous scandals have dogged the Bolsonaro family, the Brazilian state remains as sprawling as ever, and investment is so low that the economy may experience yet another recession in 2022. Yet as Lapper repeatedly makes clear, the underlying currents that led to Bolsonaro’s rise seem set to only accelerate in coming years, with evangelicals expected to become an outright majority by mid-century.

What might happen to Bolsonaro himself? It seems plausible that a different, more competent brand of conservative might rise to take his place. But there are two examples that suggest otherwise. The first is his idol Donald Trump, who, against all odds, now looks well-positioned to return in 2024. The other is Lula, whose rise from the ashes reminds us that Brazilian politicians, from Getúlio Vargas to Fernando Collor and José Sarney, very often get a second (or third, or fifth) chance at glory. Even if he loses, both Bolsonaro and bolsonarismo may be here to stay.