RIO DE JANEIRO—Earlier this month, hours after Brazil’s Congress approved a bill that would double or triple the sentences handed out to members of criminal gangs, Tarcísio Gomes de Freitas posted a short video on Instagram in which he sounded like much more than a mere governor of São Paulo state.

“Today, all law-abiding citizens have reasons to celebrate,” he said. Wearing a black polo shirt, speaking firmly, he sounded as if he himself had authored the bill—even though it was in fact mostly drafted by President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s administration. “Public security is at the center of the national debate,” he continued. “Those who can’t understand that don’t understand the country.”

It was a presidential candidate’s speech in a presidential-style video, the product of presidential-level congressional maneuvering, speaking on a topic that will almost certainly be one of the pillars of Brazil’s 2026 presidential race. So why does Tarcísio de Freitas, the hands-down favorite of investors inside Brazil and on Wall Street, keep insisting he’ll run for reelection as governor instead? Is he wary of a tough head-to-head matchup against Lula, who currently leads all major polls? Or does he think his name will be vetoed by Jair Bolsonaro’s sons, amid the discord and confusion that already reigned on the Brazilian right even before the former president was taken into police custody on Saturday?

To answer these questions, one must understand one fact above all: Tarcísio is not a traditional politician (though he is now, like most Brazilian politicians, primarily referred to by his first name). A military engineer and former army captain, Tarcísio held meaningful positions under Dilma Rousseff’s administration, as well as that of Michel Temer. In fact, he had never spoken to Bolsonaro until the then-president-elect invited him to be his minister of infrastructure, and had never run for office until Bolsonaro made him his candidate in the 2022 São Paulo gubernatorial race. Born in Rio de Janeiro and raised in a low-income household on the outskirts of Brasília, Tarcísio had only lived in the state of São Paulo during his military training; however, Bolsonaro’s support proved more than enough for him to win.

A split persona

Tarcíso is also distinctly amorphous, even by the standards of Brazil’s fluid, consensus-based politics. One moment, he professes his utmost loyalty to Bolsonaro; the next, he signals to CEOs and big business owners that he isn’t cut from the same anti-system, authoritarian cloth as his former boss. In September, at a pro-Bolsonaro rally, he called his friend Justice Alexandre de Moraes—the man who sentenced Bolsonaro’s to more than 27 years in prison—a “tyrant.”

Weeks later, he met on friendly terms with the same justices who voted to jail the former president. As governor, he participated in a series of public events alongside Lula, defying Bolsonaro, and backed the administration’s tax reform proposal. At the same time, it was he who engineered (no pun intended) the opposition’s move to hijack, rename, and champion Lula’s public security bill, turning it into one of the opposition’s likely flagship issues for the 2026 race.

That split persona is Tarcísio’s greatest asset—and potentially his greatest liability as well.

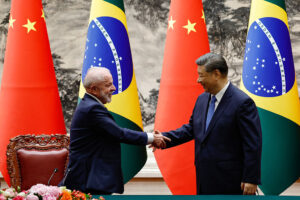

Since August, when U.S. President Donald Trump imposed a 50% tariff on Brazilian products under the premise that Bolsonaro’s trial for attempted coup was a “witch hunt,” the Brazilian opposition has spiraled into crisis. Rather than putting the Supreme Court on the ropes, the sanctions hastened Bolsonaro’s conviction, drained pro-Bolsonaro demonstrations, and shut down any possibility of securing a congressional amnesty for him. Adding insult to injury, on November 20, Trump rolled back most of the sanctions following a personal meeting with Lula a few weeks prior.

Governor of the Brazilian state with the most significant trade flows with the U.S., Tarcísio came under crossfire from both business leaders hit by the sanctions and from Bolsonaro’s third son, absentee Congressman Eduardo, who accused him of not pushing hard enough for amnesty. In interviews, Eduardo Bolsonaro blasted Tarcísio as “the system candidate, the guy Moraes wants … He’s the dummy opposition. Is Tarcísio being elected a victory for the right? No, it isn’t.”

By September, the combination of the rally-round-the-flag moment brought on by Trump’s sanctions, the ensuing recovery in Lula’s approval rating, and the public veto by Eduardo Bolsonaro led Tarcísio to announce he was out of the presidential race.

And then Lula, 80 years old and a three-time president, made a mistake.

A game-changing moment

On October 28, Rio de Janeiro’s state police carried out a massive operation against Comando Vermelho, one of Brazil’s two most powerful drug trafficking organizations. A total of 121 people were killed, including four officers, and 81 others were arrested.

In Brazil, unlike most of Latin America, public security is primarily a responsibility of state governments, rather than the federal government. It was the deadliest police operation in the country’s history—and a highly popular one: A Genial/Quaest survey showed that two-thirds of the general population approved of the raid and saw no abuse. Despite warnings from his media advisors about the public’s sensitivity on the topic, Lula dubbed the operation “a slaughter” in interviews, a stance rejected by 57% of voters.

Lula’s decision to criticize the operation publicly is part of the Latin American left’s chronic inability to address public security. The left’s central thesis—that violence is a purely socio-economic issue, and that police excess and abuses should be denounced—falls flat across Brazil, especially among those who live in impoverished areas dominated by these factions. The right wing figured that out long ago.

Convinced by Justice Minister Ricardo Lewandowski that the national outcry over Rio could be seized as an opportunity to expand the federal government’s authority over state-level public security, Lula submitted a well-crafted bill to Congress earlier this month, stiffening penalties for members of criminal gangs. That’s when Tarcísio stepped in: He persuaded Hugo Motta, the president of Congress’ House of Deputies, to name Congressman Guilherme Derrite, a former special-ops São Paulo police captain—and former public security secretary for Tarcísio—as the security bill’s rapporteur. Derrite left the bill’s backbone in place and made a few changes, giving Tarcísio just enough to pitch the bill on Instagram and elsewhere as if it were the opposition’s work.

It was also, probably, the clearest sign to date of Tarcísio’s true intentions for next year.

A defining decision

The decision, in the end, will not be up to Tarcísio alone. Without Bolsonaro’s strong support, the governor would probably endure the same fate as so-called “third way” Brazilian presidential candidates, popular with business elites but barely registering double digits in polls.

But that decision could now come sooner than previously expected. The jailing of Bolsonaro on Saturday, after he used a soldering iron in an apparent attempt to remove his electronic ankle monitor, will probably force the family’s hand.

Even if Bolsonaro’s attorneys secure a move to home confinement on medical grounds in the near future, many right-wing leaders see the episode as a turning point. Bolsonaro faces a classic prisoner’s dilemma. He can either elevate one of his sons—likely Senator Flávio Bolsonaro—and keep the family’s brand and its base intact. Or he can back a candidate who can straddle the far right and the pragmatic center, increasing the right’s chance of winning but also loosening his family’s grip on power.

If Bolsonaro decides on the latter option, “amorphous” Tarcísio seems to be the only figure capable of building a broad anti-Lula coalition. There is little doubt now he’s gearing up to do just that.