How Latin America Is Realigning

This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on China and Latin America

MEXICO CITY—While most Latin American countries are still trying to strike some kind of balance between China or the United States, the return of Donald Trump has already led to important, if sometimes subtle, shifts in the biggest geopolitical question facing the region.

Indeed, governments are taking different paths depending on their geography, domestic priorities and interactions so far with the U.S. president. The two largest economies in Latin America are moving in opposite directions, with Mexico edging closer to Washington’s orbit while Brazil takes ever greater distance from it.

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum’s government recently sent to Congress a proposal to impose tariffs of up to 50% on Chinese cars and auto parts, as well as on steel, textiles and even pharmaceuticals. If approved, the measure would also affect other Asian exporters such as South Korea and India. Officials argue the plan is designed to shield domestic industry, but its timing—coming as Sheinbaum prepares for the review of North America’s USMCA free-trade pact—suggests a broader intent. Sheinbaum’s administration has decided to side with its northern neighbor, knowing that, given the high level of economic integration, it is its safest bet. Beijing, Mexico’s second-largest supplier of goods and raw materials, has accused the country of yielding to U.S. pressure.

Brazil, by contrast, has become a case study in how to defy Trump’s demands. The White House had thrown its weight behind Jair Bolsonaro, urging that coup-related charges be dropped. Tariffs and sanctions followed when Brazilian authorities refused, including 50% levies on Brazilian exports—among the steepest Washington has imposed on any country. Yet far from folding, Brazil’s judiciary pressed ahead, convicting Bolsonaro and handing him a 27-year sentence.

For Washington, it was a diplomatic defeat: The U.S. had deployed some of its sharpest tools, only to watch Brazil celebrate its Independence Day under the banner “Brazil for Brazilians”—a slogan that resonated domestically as a rebuke of foreign meddling—soon followed by a letter from President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in The New York Times declaring: “President Trump, we remain open to negotiating anything that can bring mutual benefits. But Brazil’s democracy and sovereignty are not on the table.”

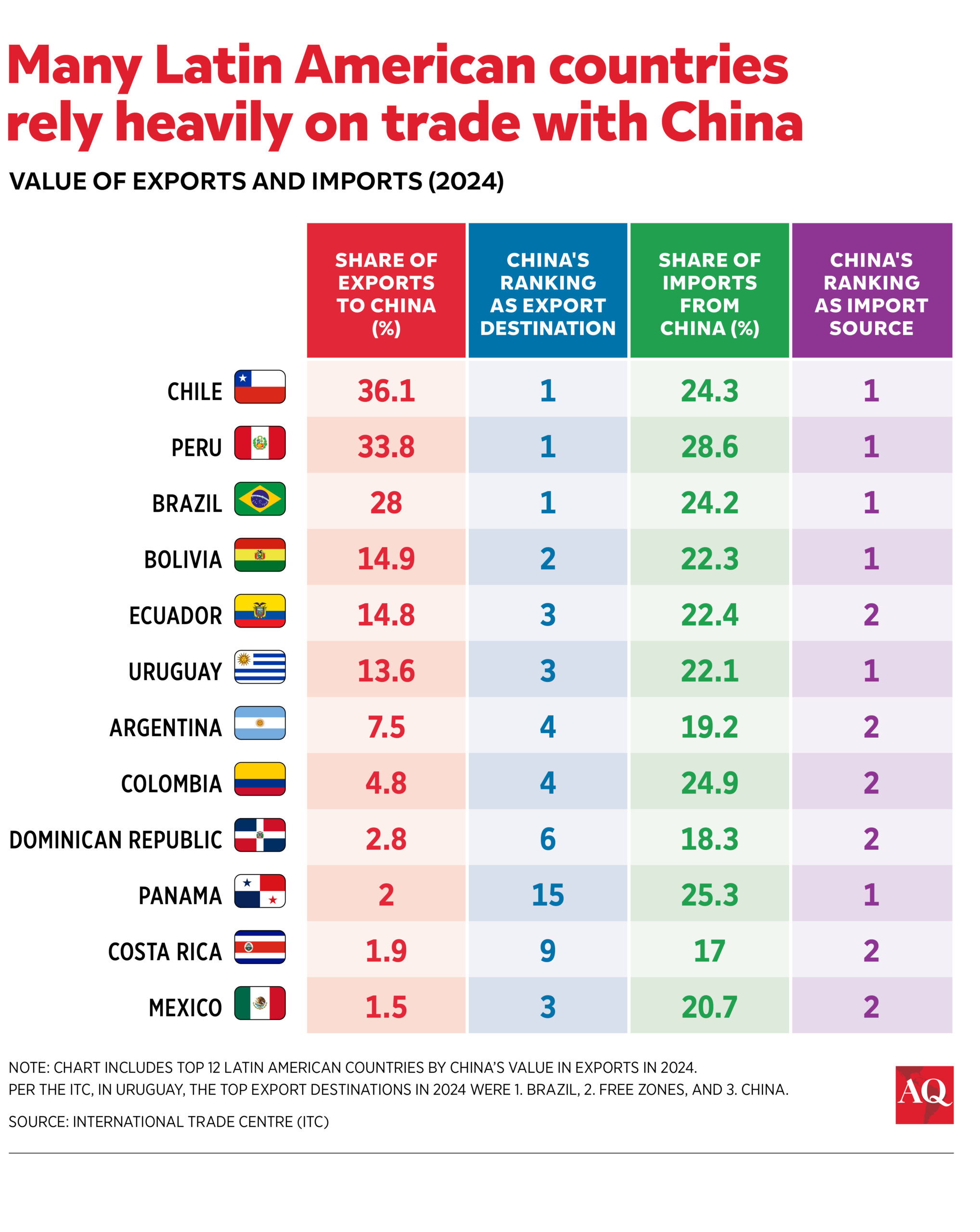

The costs of Washington’s campaign are already visible. Brazil’s exports to the U.S. have slumped, while sales to China are surging. Since Trump’s tariffs took effect, Brazil’s shipments to Beijing have risen 31%, helping to offset losses elsewhere. Public perceptions are shifting, too. A recent survey found that the share of Brazilians with a favorable image of the U.S. fell to 44% in August, from 58% in February of last year, while positive views of China rose over the same period. What was once America’s largest ally in the hemisphere is drifting further into Beijing’s embrace. Trump, however, might be ready to shift his tone. He and Lula shared a positive interaction at the UN General Assembly that the two leaders could build upon.

The steps of others

Take Colombia, a long-time close U.S. ally. In mid-September, I gave a lecture at Universidad de los Andes on “the new global disorder and business.” After the event, a participant confided that he’s worried foreign policy is being treated as a political football—whether to align more with Washington or Beijing—rather than as a state decision. The recent tilt toward China reflects more a reactive stance than a deliberate strategy in foreign policy. Earlier this year, the country joined China’s Belt and Road Initiative—a move the foreign ministry hailed as “historic”—and the BRICS New Development Bank.

Although the U.S. has been Colombia’s leading importing partner for decades, bilateral trade with Beijing has reached record levels, with China now close to overtaking Washington as the top source of imports. These moves should not be read as a definitive shift toward Beijing, but in the current geopolitical landscape, they clearly nudge the Andean nation one step away from Washington. This might explain why, for the first time in three decades, Washington has “decertified” Colombia’s anti-drug efforts, with Trump pointing to record coca cultivation and unmet eradication goals under President Gustavo Petro. Though the move places Bogotá alongside Venezuela and Myanmar, a waiver keeps U.S. aid flowing—leaving Petro facing both international censure and mounting political pressure at home.

Yet Colombia is divided. Next year’s presidential election will determine which vision prevails. For now, a May LATAM Pulse poll found that 34.5% of Colombians believe their country should tilt toward China, barely 2.5 percentage points behind those favoring alignment with the U.S.—an important shift that has been fueled by episodes such as the angry exchange of tweets between Petro and Trump in the early days of the second Trump administration.

In Argentina, President Javier Milei has sought to court Washington rhetorically, echoing Trump’s disdain for multilateralism, but economic realities are pulling in the opposite direction. China remains Argentina’s largest buyer of soy, beef and other agricultural goods, and Beijing’s currency swaps provide crucial relief to Buenos Aires’ battered reserves. In a significant boost to Argentina-China ties, China Eastern Airlines has started ticket sales for a new Buenos Aires-Shanghai flight via Auckland, set to begin in December, marking the return of a Chinese carrier to Argentina after a decade. This route, poised to be the world’s longest regular commercial flight, underscores deepening economic links.

Complementing this, the Milei administration loosened visa requirements for Chinese citizens holding U.S. visas, reciprocating China’s visa-free policy for Argentines, enhancing mobility and signaling pragmatic cooperation amid geopolitical tensions. Milei’s balancing act illustrates the limits of ideology when survival depends on trade flows.

A port and its repercussions

Peru offers another revealing case. The $3.5 billion Chancay mega-port—located 46 miles north of Lima and inaugurated last November when Chinese President Xi Jinping visited the country for the APEC summit—started formal operations shortly after Trump returned to the White House. The facility, operated by China’s COSCO Shipping, has accelerated its emergence as a direct hub between South America and Asia.

In April, the Port of Guangzhou initiated a direct service to Chancay, cutting transit times to roughly 30 days and logistics costs by about 20%. Although a Trump ally hinted at the possibility of tariffs on goods transshipped through the port, such threats have not deterred Lima from deepening ties with Beijing. For Peru, the calculus is simple: Chinese capital and infrastructure arrive faster and with fewer conditions than their Western counterparts.

Central America shows a mixed picture: While Nicaragua unsurprisingly pushes forward with Chinese-backed projects, countries like Guatemala and El Salvador tilt closer to Washington.

During the years when Washington’s attention was consumed elsewhere, Latin America slipped down its list of priorities. Now that the region has moved back up the agenda, it is under a framework of threats and tariff blackmail that has eroded goodwill. And Xi is not wasting the opportunity: He now presents himself as Trump’s opposite—predictable, pragmatic, respectful of sovereignty. In a region highly resistant to outside tutelage, this posture is well received. This has strengthened Latin America’s inclination to hedge its geopolitical bets through ambiguity rather than explicit alignment.

Many in the region understand that an effective foreign policy requires a delicate balance: safeguarding national interests while navigating great-power rivalry with strategic subtlety. Where room for maneuver is narrow and the stakes with the U.S. are vast, governments will tend to align with Washington. Yet the more Washington relies on coercion, the quicker public opinion drifts away. On the other hand, among countries with more options or looser ties to the U.S., threats are without doubt a singularly poor strategy.

All things considered, Latin America’s ties with China won’t be easily broken, and they can be more resilient than many have expected.