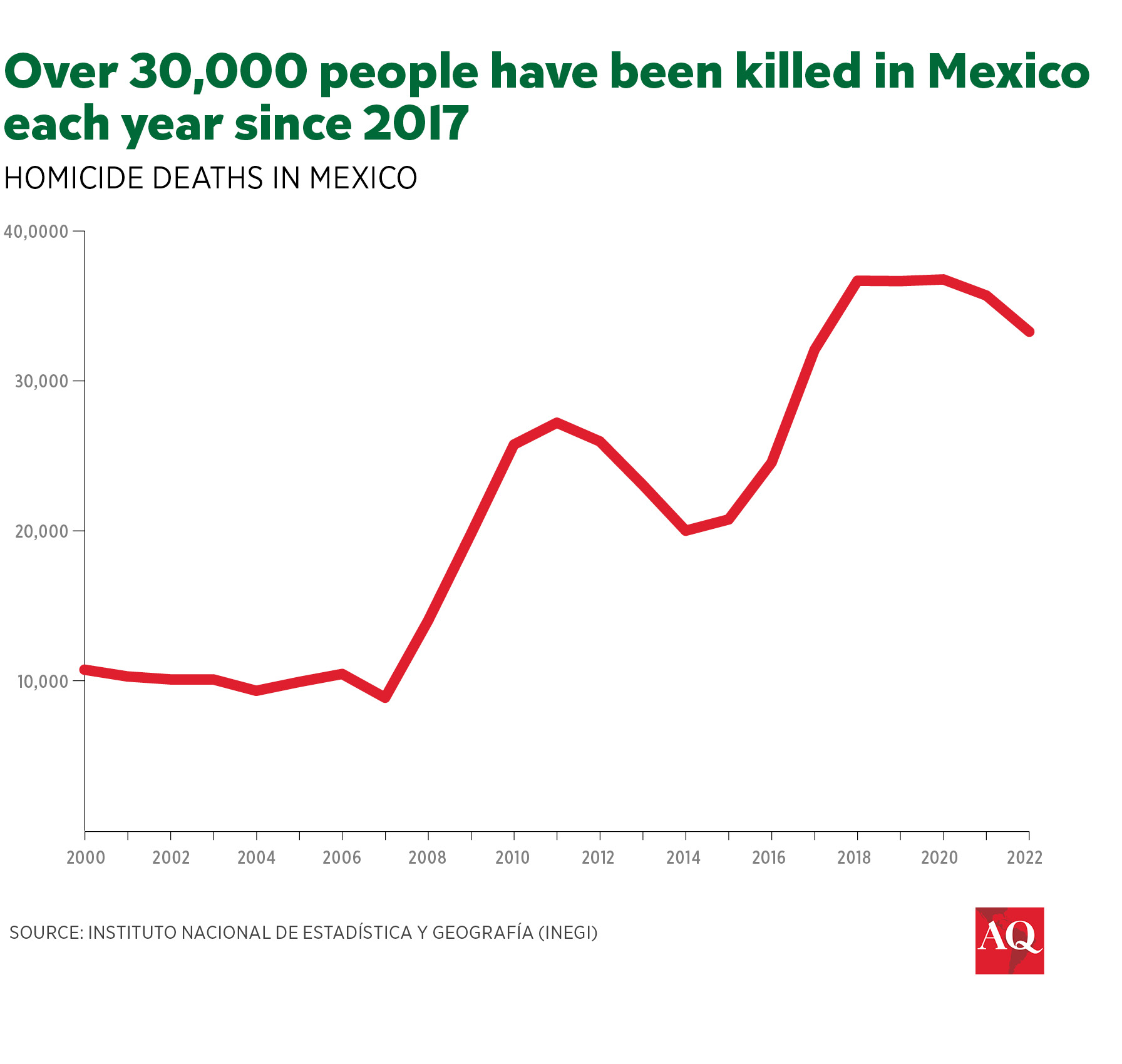

No other issue is more pressing for Mexicans than public security. Despite his widespread popularity, outgoing President Andrés Manuel López Obrador oversaw a staggering 171,085 homicides during the first five years of his term, outpacing any preceding administration. Each day, the country loses 46 individuals, either killed or disappeared, underscoring the critical challenge facing President Claudia Sheinbaum.

Mexico allocates substantial resources to combat organized crime—including an annual defense budget of nearly $10 billion—and the deployment of over 200,000 military personnel for public security tasks, and yet a survey published last month by the national statistics agency showed that 60.7% of the adult population considered public safety as the nation’s gravest problem. This security crisis constrains Mexico’s sovereignty, compromises its democratic institutions, and puts a question mark on its economic future, deterring foreign direct investment and impeding the country from realizing its nearshoring potential.

What to do about it? To fight organized criminal violence, two strategies are frequently discussed. The first is a punitive, militarized approach, known as “tough on crime” or “mano dura,” with some variations and consequences. A second option focuses on prevention, a soft-on-crime platform that addresses social and economic drivers. But this preventive approach is too long-term to be electorally expedient as a solution to cartel violence. What’s more, the legal economy perpetually struggles to compete with the lucrative illicit markets, particularly given the U.S.’s insatiable demand for drugs.

In a world where “show and tell” offers incentives, the tough-on-crime approach tends to be the more popular option. Military deployments, crime boss arrests, and suggestions of “bombing the cartels” offer quick media victories and enhance a party’s re-election prospects. For this reason, every Mexican administration since Felipe Calderón has defaulted to a militarized strategy against the cartels, regardless of ideology—from right to left. Even AMLO, who came to power championing “hugs not bullets,” swiftly militarized security policy. He vastly expanded the military’s role in political life; it now oversees infrastructure projects, tourism development, and customs operations. And just last month, the ruling Morena party further militarized public security by placing the civil National Guard under military control.

But the start of a new presidential term offers Sheinbaum an opportunity to consider and test a third option that breaks away from this unsatisfying dichotomy: a strategy based on enhanced intelligence, mediation, and deterrence that takes advantage of close collaboration with U.S. security forces to make targeted interventions before inter-cartel battles rage out of control. Her record as mayor of Mexico City suggests she may consider such a strategy. Taking this path may benefit Sheinbaum’s nascent government and the next U.S. administration, regardless of who wins the November 5 elections. The most important issues to the U.S. and its elections – the economy, crime, immigration, and the drug epidemic – are intimately linked to Mexico.

A third approach

Criminal war is the leading cause of death around the world, and most violence occurs along turf boundaries between organizations following shocks to the balance of power between gangs. Intelligence should carefully map cartel territories and borders to detect and prioritize hot spots. Authorities should then mediate between the rival criminal groups to defuse conflicts before they turn violent—akin to the “violence interrupter” approach now used in some U.S. cities.

Such mediation presents significant ethical and practical challenges. Critics argue that such an approach could be seen as “negotiating with gangs,” potentially legitimizing their power and opening avenues for corruption and further state infiltration. This could be particularly problematic for Morena, given its critique of past governments’ corruption and handling of the drug war. Any mediation strategy must be carefully designed and implemented to avoid these pitfalls and maintain public trust.

Sheinbaum’s standard operating procedures and record as mayor of Mexico City suggest she could be well poised to implement this third approach. During her tenure as mayor, she halved homicides in the capital city, in large part by relying on civilian policing, bolstering the police’s investigative capacity, incentivizing cooperation with prosecutors, and sharing intelligence with U.S. law enforcement agencies.

There are signs that she may continue these policies as President. She has appointed her Mexico City security chief, Omar García Harfuch, as security minister (albeit with decreased powers), and she has promised to create a new national intelligence agency and binational working groups on security issues, signaling a potential shift towards more sophisticated policing strategies and an emphasis on targeted operations.

Still, some speculate that her security stance will continue AMLO’s militarized strategy. Sheinbaum has pledged to maintain the armed forces’ prominent role in public security, indicating that she may fall into the same trap as AMLO: public rhetoric of reform but punitive policies in practice.

Additionally, deterring criminal violence requires sweeping reforms to the judicial system, which currently resolves only 1% of crimes. The 2024 judicial reform, while ostensibly aimed at addressing systemic issues, has been criticized for potentially concentrating power in the executive branch rather than addressing the fundamental problems of impunity and inefficiency plaguing the justice system.

This ‘third approach’ – enhanced intelligence, mediation, and deterrence – will require improved bilateral cooperation between the U.S. and Mexico focused on information sharing: a security version of the USMCA, a reincarnation of the dead Mérida Initiative, the $3 billion U.S. aid program that for more than a decade fostered security cooperation between the two countries.

Of course, such a security alliance would require mutual trust, which is not forthcoming, in part due to U.S. officials’ suspicion of their Mexican counterparts, especially after Genaro García Luna, the highest-ranking law enforcement official in Mexico during Calderón’s administration, was convicted in the U.S. on drug trafficking charges. But this lack of trust is also due in part to Morena’s concerns over sovereignty, making Mexican administrators wary of meddling by their northern neighbors. In August, AMLO “paused” relations with the U.S. embassy, alleging interference in the country’s internal affairs.

Creating cross-border political will

There are a few realms where Sheinbaum could enhance the bilateral relationship with the U.S. to create the political will for security cooperation.

Fentanyl, in particular, is giving the Mexican cartels an unprecedented financial “high” while causing over 100,000 American fatal overdoses last year alone. The U.S. and Mexico should, therefore, seek an alliance to disrupt fentanyl precursor chemical supply chains and coordinate actions against the global financial networks and darknet vendors of illicit drugs, raging havoc on both sides of the border.

Mexico and the U.S. also face increasingly aligned interests on migration. Both are now receiving countries of migrants from all around the world. Both face hundreds of thousands of backlogged asylum cases that have overwhelmed their systems. Domestic pressures to crack down on migration exist on both sides of the border.

And economically, while the USMCA renegotiation looms large, the U.S. and Mexico face a common goal of interdependence; Mexico is the U.S.’s biggest trading partner (a relationship worth $807 billion a year) and the top exporter of goods to the U.S. Amid intensifying rivalry with China, the U.S. needs Mexico to move supply chains closer and counter China’s growing influence in Latin America. Mexico, in turn, needs the U.S. to fulfill the economic transformation such a trade relationship entails.