Peru’s Congress is recklessly dismantling the nation’s crime-fighting institutions to the benefit of the country’s mafias—increasing the risk of instability, outmigration, and manipulation by malign foreign actors.

Last month, Congress passed a law that bars prosecutors from investigating migrant trafficking, illegal logging, embezzlement, and 56 other offenses that carry prison terms of six years or less as organized crime offenses. That means both less time to investigate such cases and more hurdles to placing suspects in pretrial detention. The law, which went into effect on August 9, also bans investigators from raiding suspected criminal headquarters to gather evidence, even after obtaining a warrant, unless the suspect in question and a defense lawyer are physically present.

Peru’s leading private sector organization, the National Confederation of Private Entrepreneurial Institutions (CONFIEP), took the rare step of urging Congress to shelve the law, and the Public Ministry (prosecutor’s office) announced it would file a constitutional complaint against it. In a June poll, 75% of respondents said they opposed the changes to the rules on raids. But Congress, with just 4% public approval, didn’t listen.

Still, there is one set of voices that might get lawmakers’ attention, if they speak forcefully enough: the U.S. State Department and its European counterparts. They have every reason to push back. For over a year, the coalition of parties in control of Congress—the real locus of power in Peru, given the political weakness of President Dina Boluarte—has been reducing authorities’ capacity to investigate crime. Congress restricted prosecutors’ ability to strike plea deals, amnestied illegal logging offenses committed before 2024, passed a law stopping police from seizing explosives from illegal miners, and diluted the organized crime law. Now, Peru’s ombudsman, a close ally of Congress, is seeking to have Peru’s asset forfeiture law declared unconstitutional, which would make it much harder and slower for authorities to seize guns, houses and other assets from criminal groups.

If Congress continues weakening law enforcement—jeopardizing regional stability in the process—there must be a coordinated international response.

This is the worst possible time for Peru to lose crime-fighting capacity. Organized crime is not new for the country, but recent brazen attacks are. Over the past few weeks, two union leaders, under threat from extortion gangs, were gunned down within 24 hours of one another; the country’s largest gold mine was once again attacked by illegal miners; and a prominent Indigenous leader in the Peruvian Amazon was slain after denouncing narco-traffickers.

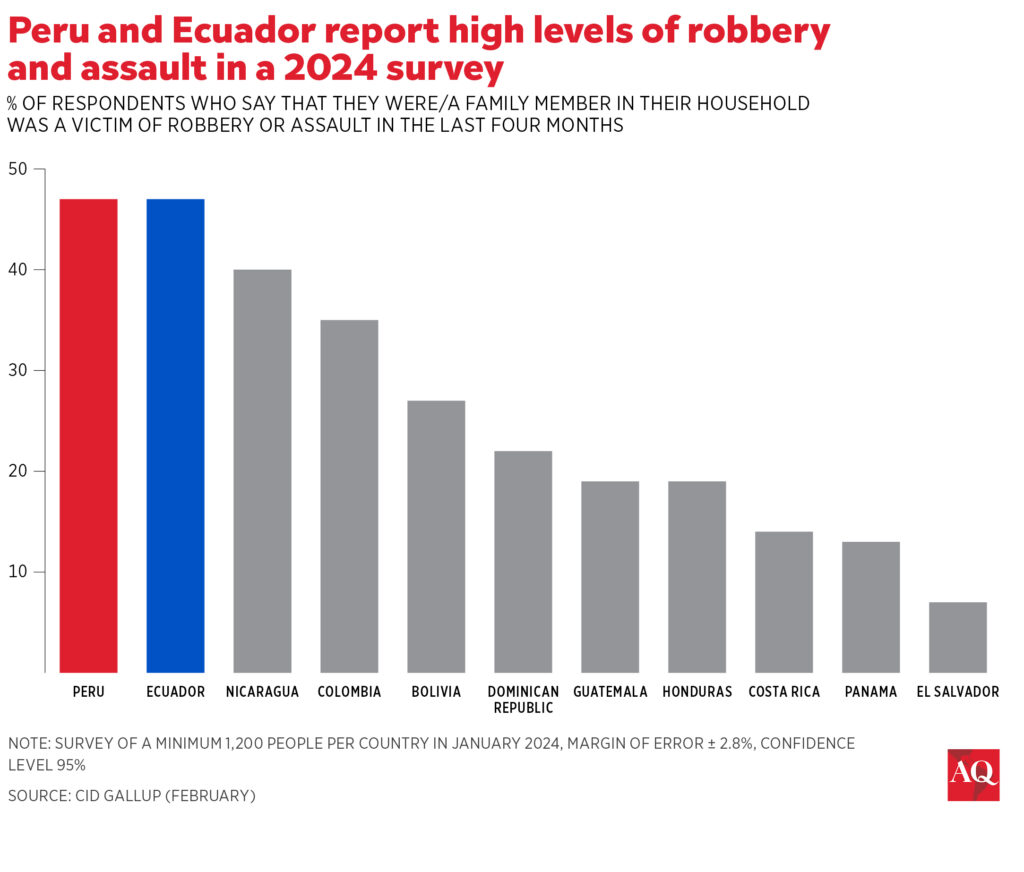

These are not the only signs mafias are becoming more powerful than the state. Extortion cases quadrupled nationwide from 2021 to 2023 (from just under 5,000 per year to over 22,000), according to prosecutor’s office data, spreading to all corners of the country and economy. Illegal miners, Peru’s biggest criminal earners, exported some $4.8 billion in illegal gold in 2023, nearly half of the South American total, and are deforesting the Amazon and clogging roads mining companies need for exports. Since the pandemic, Peruvian cocaine traffickers have partnered with Colombian and Brazilian criminal groups to extend large-scale coca cultivation to new parts of the Amazon. Members of the Albanian mafia are increasingly turning up in Peruvian ports, as they did in Ecuador, before it entered its violent downward spiral. Don’t let Peru’s low homicide rate fool you. This is what a crisis looks like before it erupts.

Pressure isn’t pointless

With the Andes already in turmoil from Venezuela to Ecuador, it is not in the interest of the U.S., Europe, or Peru’s neighbors to allow one more country to slide into crisis. But the approach to date—of appeals to shared democratic values, photo-ops with embattled independent judges, and closed-door discussions—doesn’t seem to be working.

U.S. and European diplomats should consider a more proactive approach involving consequences for the leaders of Peru’s major parties if they continue weakening rule of law or attempt to compromise the independence of Peru’s electoral institutions before the 2026 elections.

A few doubts might be holding diplomats back: Could greater international pressure push Peru into China’s arms? Could it heighten Peru’s political instability? Or could it simply fail to sway lawmakers?

First, on China. If the goal of expressing concern about rule of law erosion gently, and mostly in private, has been to woo Peru away from China, it clearly isn’t working. Under Boluarte, Chinese firms recently have attained a monopoly on Lima’s power supply and will soon inaugurate the mega-port of Chancay, a facility with dual-use capacities and the first Chinese-owned logistics hub in Latin America. In June, Boluarte visited Beijing to upgrade Peru-China trade ties and sign a deal to have tech giant Huawei train 20,000 Peruvians, and Chinese military officials visited Lima in January to talk joint exercises.

Boluarte and the parties that currently dominate Congress are likely too unpopular to survive the 2026 elections, provided they leave electoral institutions intact and that vote is free and fair. A more effective way to compete with China, long-term, would be to focus on building credibility among the Peruvian people—and whatever leadership they choose next—by pushing back firmly against Congress’ anti-rule of law agenda now.

Second, stability. The Peruvian government may no longer be the carousel of ministers it was under former President Pedro Castillo. But it’s not only frequent turnover in personnel that generates instability. It’s also reckless, destructive policy. Congress’ weakening of law enforcement sets the stage for more social conflict, more criminal violence, and likely more protest and outmigration—in a word, for instability. A foreign policy that doesn’t factor this in won’t reinforce political stability; it will enable its erosion.

Last, the efficacy of pressure. Some may worry that those in charge of Peru’s major parties, who set the agenda in Congress, will not be as responsive to measures like visa restrictions as, say, Guatemalan lawmakers were last year. But that’s far from certain. Peru’s political party leaders travel often to the U.S. and Europe, own expensive homes there, and have family members, kids in university, and private business deals there. This is not true of the average member of Peru’s Congress, but they are not the decision-makers—the party bosses are.

Fortunately, not all those party leaders are equally committed to weakening law enforcement. Some have thick case files in the prosecutor’s office and open investigations for illicit campaign finance. Others are along for the ride and can be convinced to stop—if there are costs to continuing.

Diplomats should prevent these party leaders from stripping even more power away from law enforcement and meddling in electoral institutions before 2026. If not, they risk dealing not with a normal government after the next elections, but with a mafia state.