BOGOTÁ — The Instagram account still exists: barranquilla2027oficial. It was created after Colombia’s most important Caribbean city was chosen to host the next Pan American Games, bringing together thousands of athletes from dozens of countries in the Western Hemisphere.

However, despite the promise, nothing of that sort will happen. A long letter addressed to Colombian President Gustavo Petro on January 8, signed by the president of Panam Sports, Neven Ilic, listed seven commitments unfulfilled by the Colombian government. Although several extensions to the contract’s original terms were granted, nothing happened, promises were broken, and patience ran out.

For many, the frustration of losing the chance to host the most important sporting event in the hemisphere underlines the problems of a government particularly vulnerable to self-inflicted wounds. This, combined with a challenging economic climate and unfulfilled expectations, has been costly for the first leftist president in Colombia’s 200-year-old democracy.

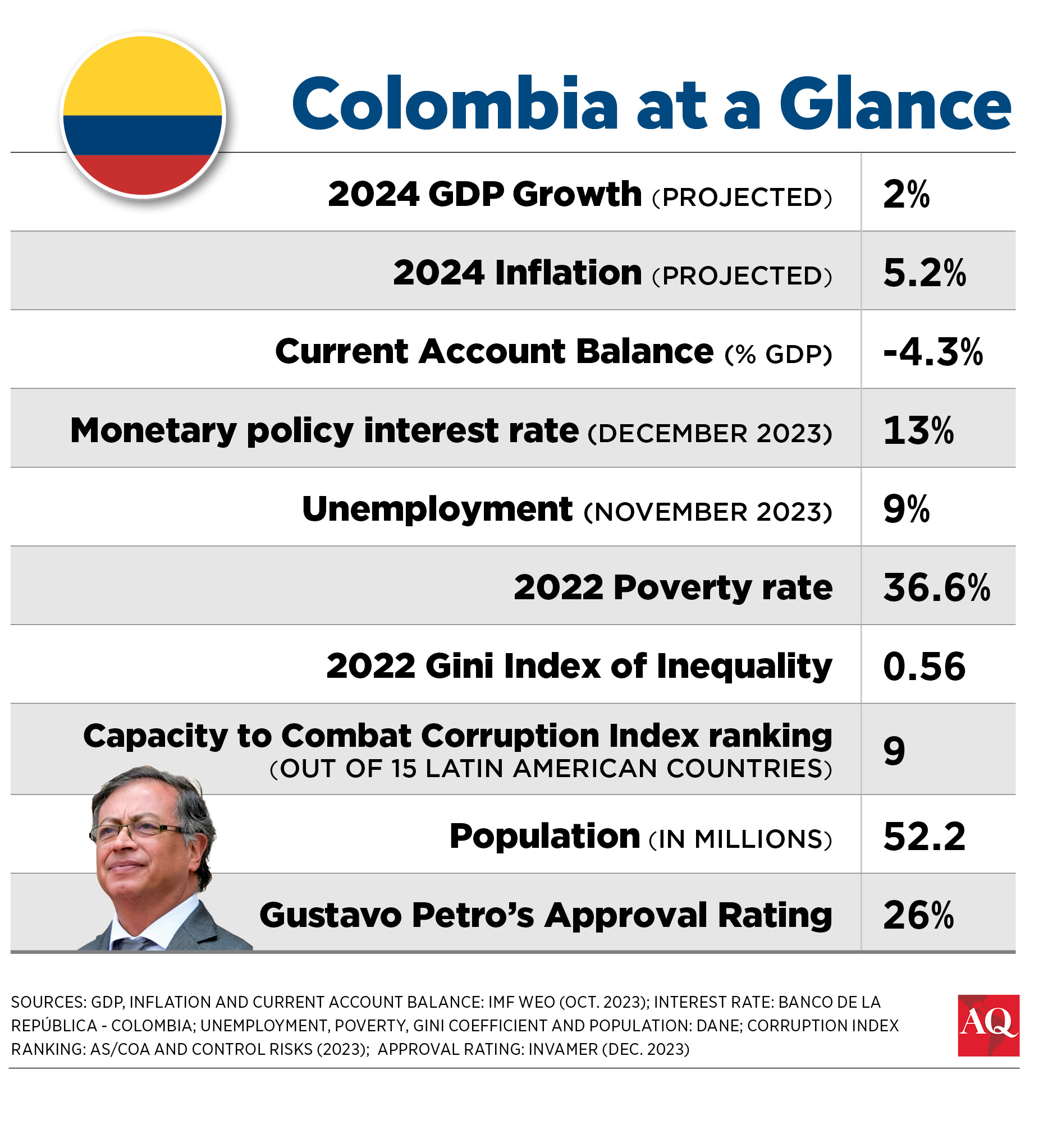

Petro seems to be embattled on all sides, navigating an ever more difficult labyrinth of his own creation. According to pollster Invamer, his approval rating was a mere 26% last December, a loss of 22 percentage points in 12 months. Conversely, his disapproval increased to 66%, a 22-point increase in the same period.

Why the change? “It is a mixture of things,” explained analyst Leonardo García. “The grievances range from his perceived lack of discipline in the job to a series of radical positions and political mistakes that have annoyed voters from the center and disappointed citizens in general,” he added.

The news outlet La Silla Vacía showed that Petro was a no-show at 82 public events during his first eleven months in office. He’s been late to dozens of meetings and ceremonies, sometimes by hours. Most of the time, explanations cite his “private agenda.” His punctuality has improved lately, but the damage has been done, giving way to rumors.

Last November, a respected columnist and Petro supporter, María Jimena Duzán, wrote an open letter to the president. “There are sources that assure me that the reason for your disappearances, which have become more frequent and prolonged, has to do with your desire to keep an addiction problem hidden,” said the text.

After recommending treatment, the message reminded Petro that “you don’t have the right to live a double life.” The last paragraph is particularly troubling: “You have said that drugs are a public health issue (…). Confessing that you have an addiction can’t be a sin or a shame, but an act of deep honesty.”

Nothing happened afterward, but the allegations from someone considered personally close to the president cemented the narrative of a dysfunctional government led by an unreliable pilot. Ministers confess in private that weeks sometimes pass before they talk to their boss, who dedicates much of his time to posting on X (formerly Twitter). During his first year in office, Petro tweeted 2,512 times.

“He likes the role of head of state, not the public administration part of it, and presents himself as a deep thinker concerned with the future of humanity,” García added. “Time Magazine calls me a philosophical economist. I try to be. But I am more of a transformer,” Petro wrote in mid-December.

Politics and more

At the beginning of 2023, the new government seemed unbeatable after passing an ambitious tax reform thanks to a powerful coalition in Congress. Things began to change in February when tensions between moderates and radicals inside the Cabinet surfaced. The minister of education departed, and three critical social reforms began their legislative process on the wrong foot. These health, pension, and labor regulation proposals are still pending today. Other vital issues on the agenda have been abandoned or remain entangled in the legislature.

When the road became steep, Petro first tried to use the power of the streets. But his calls from a balcony at the presidential palace mainly fell on deaf ears. At the same time, his son Nicolás and brother Juan Fernando were accused of receiving illegal campaign donations. The judicial process is far from finished, but the image of a politician who had distanced himself from the political parties’ traditional practices was tarnished. Later, another scandal affected his chief of staff and Colombia’s ambassador to Venezuela, who spoke of unaccounted-for money in the presidential campaign in a recording.

Instead of trying to fortify his coalition through negotiations and a Cabinet reshuffle, Petro shifted left, annoying some of his allies. Loyalists replaced moderates last April, and Congress took note. Only essential initiatives—the National Development Plan or the 2024 budget—were passed in the previous year.

At the end of October, another sign of weakness emerged in municipal and regional elections. The candidates supported by Petro’s Pacto Histórico coalition were defeated in all the major cities and most governorships. In Bogotá, Petro’s longtime ally Gustavo Bolívar—who had resigned from the Senate to run for mayor—came in third.

The “total peace” initiative aimed at simultaneous negotiations with more than 40 armed groups experienced numerous setbacks. A ceasefire with ELN—the only remaining active historical guerrilla group—was agreed upon, but in different parts of the country, the situation has deteriorated.

Statistics show that the number of mass killings remained at more than 90 in 2023, according to Indepaz, a think tank. The minister of defense reports that kidnappings and extortions are on the rise, while the number of killings may also have risen.

A lackluster economy

And there is the economy, of course. After being one of the top performers in Latin America, Colombia experienced a notorious slowdown: GDP growth went from 7.3% in 2022 to 1.2% last year, according to the World Bank. Part of the reason is a contractionary policy pushed by the Central Bank to tame inflation, which ended 2023 at 9.3%. But that is not the only problem.

According to official figures, during the first nine months of last year, internal demand fell by almost 4%, mainly due to a 22% decline in productive investment. The National Association of Entrepreneurs (ANDI), the country’s most important trade association, said in a report that this behavior is explained not only by the economy but also because of many uncertainties (legal, public policies, reforms before Congress) as well as a lack of security in the country.

GDP forecasts for 2024 hover around 1.5%, which would be insufficient to keep unemployment down. This, combined with profound fiscal challenges and a complex social situation, led S&P Global Ratings to put Colombia in a negative position regarding its obligations in mid-January. “A potentially weak and persistent investor confidence” would affect future growth, said the rating company in its report.

In the longer term, there are worries about how Colombia will transition from hydrocarbons after Petro decided to stop signing new exploration contracts. “Oil is death,” he said in Davos, attacking the country’s number-one export. (Coal is the second.) The bet is that tourism will replace lost income from extractive industries, but that remains to be seen.

For the moment, with two-thirds of his mandate still pending, Petro will face mounting difficulties. Social and economic unrest and a deteriorating security environment will plague the rest of his term, making life for many Colombians more difficult. It is no wonder that migration records show that one million people, mostly young, left the country over the past two years. More could follow if the administration that rose to power with a promise for change ends up changing things—but for the worse.

—

Ávila is a senior analyst at El Tiempo and a political consultant in Bogotá, Colombia.