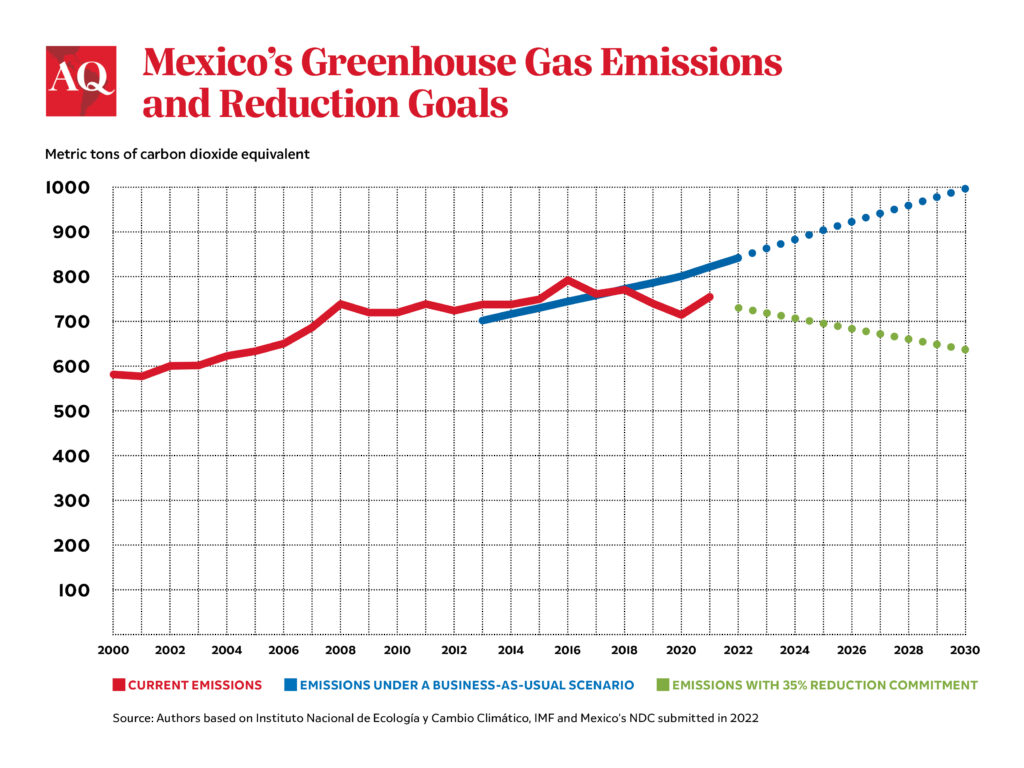

Next year, Mexicans will choose a successor to President Andrés Manuel López Obrador for the 2024-2030 presidential term, or sexenio. This will not be an ordinary sexenio: At stake is whether Mexico will be able to deliver on the country’s climate pledge of a 35% emissions reduction by 2030 under its Paris Accord commitment.

Whether Mexico, the world’s 14th largest economy, achieves its climate commitments is of relevance not only for the next president’s international and domestic credibility and the country’s future competitiveness. It is also of global relevance. Mexico is the 12th largest crude oil exporter (the second largest crude exporter to the U.S.), and among greenhouse gas (GHG) emitters it sits at number 14. And in terms of methane, believed to be significantly more damaging to the atmosphere than carbon dioxide, it is among the 10 largest emitters in the world. Despite Mexico’s global relevance, it is the only G-20 country that has yet to pledge a net-zero emissions goal, something that more than 130 countries have already committed to.

Last November, Mexico submitted a revised National Determined Contribution (NDC)—which are the plans presented by each country as part of their Paris Accord climate commitments—pledging to reduce its emissions by 35% in 2030. It will be up to the next administration to deliver a plan on how to bring emissions down and prepare the country for an era of extreme weather events.

While a 35% emissions reduction might sound like an untenable goal to reach in six years, in reality this number is closer to 20%. Mexico’s target was in reference to a business-as-usual scenario which assumes a 25% increase in emissions by 2030 compared to 2019. The good news for Mexico—and the world—is that such an aggressive emissions trajectory is not likely to materialize. The IMF estimates that under a business-as-usual scenario that takes into account the current emissions trajectory and policy landscape, the increase would be closer to 7% between 2020 and 2030.

However, even this more attainable target will not be met without a plan. To put things into perspective, Mexico’s GHG emissions fell by only about 3% in 2020, despite the economy shrinking 8% in a pandemic-related recession—a testament to the emissions of legacy infrastructure and economic processes. The challenge for Mexico in the next sexenio is to achieve its pledged reductions by tapping into the significant opportunities that the energy transition could represent, in terms of investments and growth, to reduce the costs of such transformation.

Mexico has many things going for it. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and U.S. economic tensions with China represent a significant opportunity for near- and friendshoring. In addition, the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act, which unleashes about $400 billion in climate-related funding, could open up significant investment opportunities for Mexico to become part of new clean energy supply chains. Yet, government action is key to unleashing this kind of opportunity.

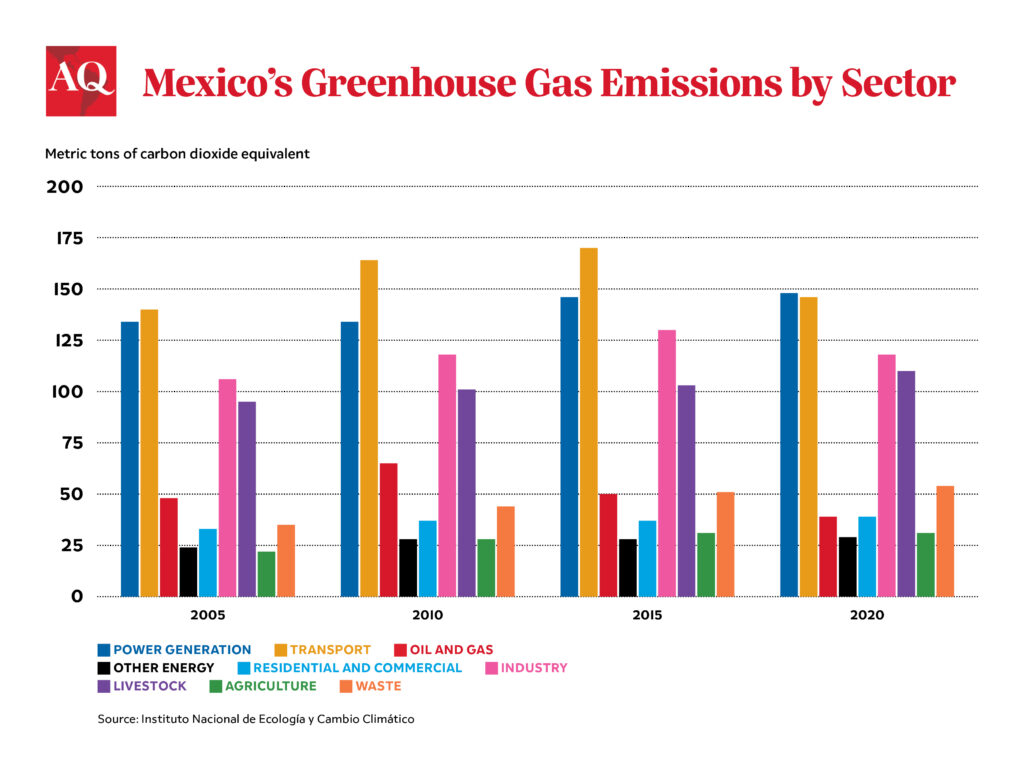

Mexico’s current NDC places reforestation and better land use at the center of how the country plans to meet its emissions pledges. Indeed, a responsible approach to biodiversity is essential and needs to be a critical part of the equation. But it will be difficult for Mexico to meet its climate targets without also addressing the current emissions of the power, transportation and oil and gas sectors, which represent the bulk of Mexico’s emissions, and are key for Mexico’s future economic competitiveness. This approach is in line with other studies and proposals, including from Mexico’s National Institute of Ecology and Climate Change (INECC) and the NGO Iniciativa Climática de México (ICM).

On transportation, which is the second largest source of emissions in Mexico, some policy action and an increasing fleet of more fuel-efficient vehicles resulted in a 10% emission reduction from this sector in the last decade. That underscores the power of policy and technology in helping to reduce emissions. What makes transportation particularly relevant in Mexico’s case is that more than a third of the country’s total exports are linked to the automobile industry. This industry is undergoing a significant transformation with the expansion of electric vehicles. Tesla’s recent announcement of a new factory in the state of Nuevo León is big news for a country that needs to make sure it is part of the industry’s future. Other companies have also announced plans for EV production in Mexico. The requirements of these companies for clean energy in their operations are only going to increase.

Power sector: Bridging the gap between pledges and action

Unlike many South American countries where renewables account for 60% or more of the electricity mix, in Mexico the share of non-fossil fuel power generation is about 28%, according to the Latin American Energy Organization (OLADE). This puts Mexico behind its USMCA trading partners Canada—where non-fossil fuels represent more than 80% of the country’s electricity—and the U.S., where renewables are 20% of the power mix, but, adding nuclear, the share of non-fossil fuels is already at 40%.

Mexico’s power sector is the main source of the country’s GHG emissions, and emissions have grown rapidly. The increase would have been even steeper had it not been for the electricity auctions held under the previous administration, which resulted in about 9 GW of solar and wind capacity added in the last five years. Solar and wind-based electricity now account for about 12% of Mexico’s generation, compared to only 3% in 2017. This also contributed to a 50% reduction of coal-based power generation and, to a lesser extent, of oil-based generation compared to 2017.

Unfortunately, this process came to a halt under the current administration leading many analysts and international agencies to voice their disappointment and concern. As a result, Mexico will likely miss one of the key goals embedded in its energy transition law of achieving 35% of clean power generation by 2024.

However, the new NDC submitted by the current administration continues to uphold clean energy ambitions, as seen in the goal of adding 40 GW of non-fossil power capacity, up from almost 30 GW currently, by 2030. Embracing this ambitious target is a step in the right direction for Mexico to capitalize on its abundant renewable energy resources. But the next government’s to-do list will also include the goal of finding a mechanism to deploy the level of investment needed to reach these non-fossil power targets. While state-owned electricity company CFE’s recent move into renewables is welcomed, a handful of solar energy projects to be built by CFE will not be enough. According to ICM’s analysis , to meet its climate commitments, Mexico will need to add, before 2030, the equivalent of three to four times the clean electricity projects added in the last five years. No government or state-owned company has the balance sheet to do this alone.

The outlook for meaningful growth of renewables in the country is highly uncertain without an effective partnership with the private sector. Clean energy auctions have proven to be a successful mechanism in Latin America and in Mexico for deployment of renewables into the power grid, but the Mexican government canceled the last one in 2019.

Oil and gas sector: Start with Pemex’s methane emissions

Tackling GHG emissions from the oil and gas sector is going to be challenging everywhere in the world. But in Mexico’s case, lack of progress on emissions reduction in this sector could have very negative financial implications for Pemex, the national oil company, and thus for the government. Mexico’s revised NDC has a goal of reducing GHG emissions by 14% in the oil and gas sector by 2030. The next administration will also be on the hook for delivering on this pledge.

One of the most urgent issues is methane emissions. According to official data, the amount of methane that is either vented or flared rose by 150% between 2019 and 2021 and is equivalent to 10% of the country’s total domestic gas production. Had Mexico developed the infrastructure to capture these methane emissions it could have saved $1 billion by avoiding about 8% of the gas it imported from the U.S. Talk about an effective energy security measure!

A sign that the Mexican government understands the global relevance of curbing methane emissions is its membership in the Global Methane Pledge (GMP), a global effort to collectively reduce methane emissions by 30% by 2030. Recent announcements about a collaboration between Pemex and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to provide technical capacity to tackle methane emissions are encouraging.

In a world of net-zero pledges, Pemex’s subpar environmental performance will only compound its credit challenges, already problematic given its debt overhang and financial woes. Thus, tackling Pemex’s environmental performance is becoming particularly relevant if the state owned oil company wants to maintain access to the financial sector. In this respect, the Foreign Ministry’s announcement last year of a $2 billion investment plan to reduce Pemex’s methane venting and flaring is encouraging, although there are no further details. However, for all of this to go beyond announcements, government action is crucial.

Many companies have pledged to become net-zero by 2050, including some based in Mexico. Access to finance is likely to become increasingly selective according to the credibility of climate credentials. Therefore, among the next government’s urgent to-do-list goals will be the decarbonization of its own power and oil state owned companies. Given CFE’s and Pemex’s quasi-monopolistic position, reducing emissions in the power and oil and gas sectors depends on it. And without progress in these two sectors, it is going to be very difficult for Mexico’s next president to reduce emissions, let alone deliver on the current climate pledges by 2030.

The good news is that Mexico is particularly well placed to capitalize on the many opportunities that the energy transition represents. It will be up to the next government to make sure it does.

—

Palacios is a senior research scholar at the Center on Global Energy Policy and Adjunct Professor at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs. She is a member of AQ‘s editorial board.

Rivera Rivota is a Research Associate at the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs. He is a member of the Mexican Council on Foreign Relations (COMEXI).