When the center-left Chilean politician Carolina Tohá was mayor of a central district of Santiago from 2012 to 2016, she was a lightning rod for criticism from leaders of an energized, left-wing student movement.

One of them was none other than Gabriel Boric, who took to Twitter to accuse her of perpetuating a “progressive double standard” and “opportunism.”

Now, Boric is president of Chile—and has turned to the experienced Tohá to help his government recover from a wave of recent setbacks. Following the rejection last month of a proposed new constitution that he had supported, Boric named Tohá interior minister, a position widely perceived as the second-most powerful in Chile’s government. (Chile’s system does not include a vice president.)

Tohá, 57, replaced Boric’s friend and fellow thirty-something Izkia Siches, who made several missteps and was criticized as being too inexperienced for such a broad portfolio.

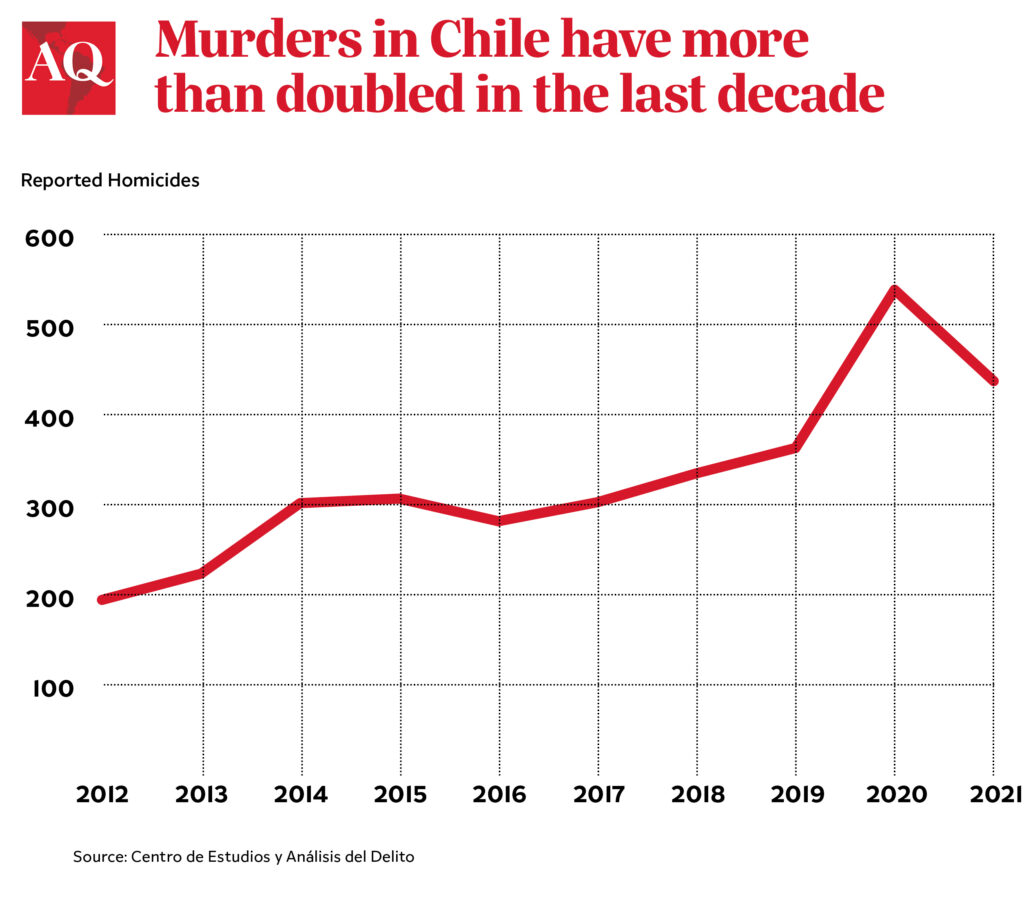

The tasks ahead are formidable. Boric’s approval stands at just 33%, and his ambitious agenda for change to the country’s social system is largely on hold. It is still unclear how a new constitutional assembly will take place. Tohá’s profile includes domestic security, and homicides are up by almost a third so far this year, part of a long-term upward trend, making it one of the most pressing challenges facing the government.

Chile’s economy is also among the worst performers in Latin America, with expected growth of just 2% this year and a contraction of 1% forecast for 2023, according to recent forecasts from the International Monetary Fund.

By naming a center-left figure 20 years his senior to such a critical post, Boric appears to be reaching out to a generation that ran Chile prior to the 2019 protests that shook the country. In this case, age isn’t just a number: The generational and political divides are real.

History, political and personal

Tohá has a last name with deep connections to the violent second half of Chile’s twentieth century: Her father José held the same interior minister job under Salvador Allende. He died in 1974 after being imprisoned and tortured by the military dictatorship.

Carolina Tohá’s career has been intimately bound up with the center-left Concertación coalition that has dominated Chilean politics off and on since the return to democracy.

A founding figure of the Party for Democracy (PPD) when she was still in her twenties, she has held a number of government positions, including a ministerial post under Michelle Bachelet, and the mayorship of central Santiago, losing reelection in 2016 amid allegations of irregular contributions related to her time as PPD president. (She denied any wrongdoing.)

Observers say the district is a difficult one—few recent incumbents have managed to be reelected. “For her it was really hard,” said Paula Schmidt, a journalist and professor at the Universidad de los Andes. “She wanted to be mayor again.”

A generational divide

Carolina Tohá now takes her place as a representative of an older, more center-left generation in Boric’s cabinet, alongside Mario Marcel, the moderate, experienced finance minister, and Ana Lya Uriarte, a former Michelle Bachelet cabinet chief now in a role dedicated to liaising with Congress.

Another group in the cabinet is made up of younger figures associated with a more left-wing set of parties—including the Communist Party. These include the government spokeswoman, 34-year-old Communist Camila Vallejo, and the minister for women, 32-year-old Antonia Orellana.

“There are two cultures at play,” said Sergio Bitar, a PPD veteran who was imprisoned with José Tohá and later served as minister in several administrations. “One took shape under a brutal military dictatorship and (sought) a majority for progressive reforms, to consolidate democracy and achieve practical advances. Another culture is that of a new generation, born under democracy and economic progress, that finds these changes to be insufficient … and puts more emphasis on the future, especially on climate change.”

Some see Tohá, who is a younger member of the older generation, as a potential bridge between the two. “She can help balance … these two forces that are within the coalition and are very dissimilar,” said Jaime Bellolio, member of the conservative UDI party and minister under Sebastián Piñera.

But it isn’t only a clash of generational outlooks: There are policy differences, too, including over the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal, or TPP11, which is causing tensions in the government, with the Communists staunchly opposed and the center-left in favor.

The trade agreement was approved by the Senate on October 11 and now awaits Boric’s approval—but some outlets reported he was expected to delay signing.

Another massive open question is the constitutional one. Voters seem to have decided the draft presented to them in September was too identitarian and left-leaning, but the massive 78% majority that voted for a new charter back in 2020 means the process must continue. But how? Boric, along with the left, wants another assembly—but forces closer to the center want a process more stage-managed from Congress. The Senate, in particular, seems eager to ensure the process does not threaten its own existence. (The rejected draft would have scrapped it.)

“Congress wants a rubber-stamp (constitution-writing) body that ratifies the constitution that Congress wants,” said Patricio Navia, a professor at NYU and at Chile’s Diego Portales University. With this dynamic in mind, Tohá’s challenge is to make sure Boric’s government recovers some say over constitutional matters.

Security an issue

Besides her role in getting Boric’s government back on track, Tohá must face a trio of interlinked public safety challenges menacing the country: the rise of narcotrafficking and gang activity in the north, something to which Chile is not accustomed; a sense of deteriorating public safety in the capital, Santiago; and conflict in the south between security forces and Indigenous Mapuche groups over land rights.

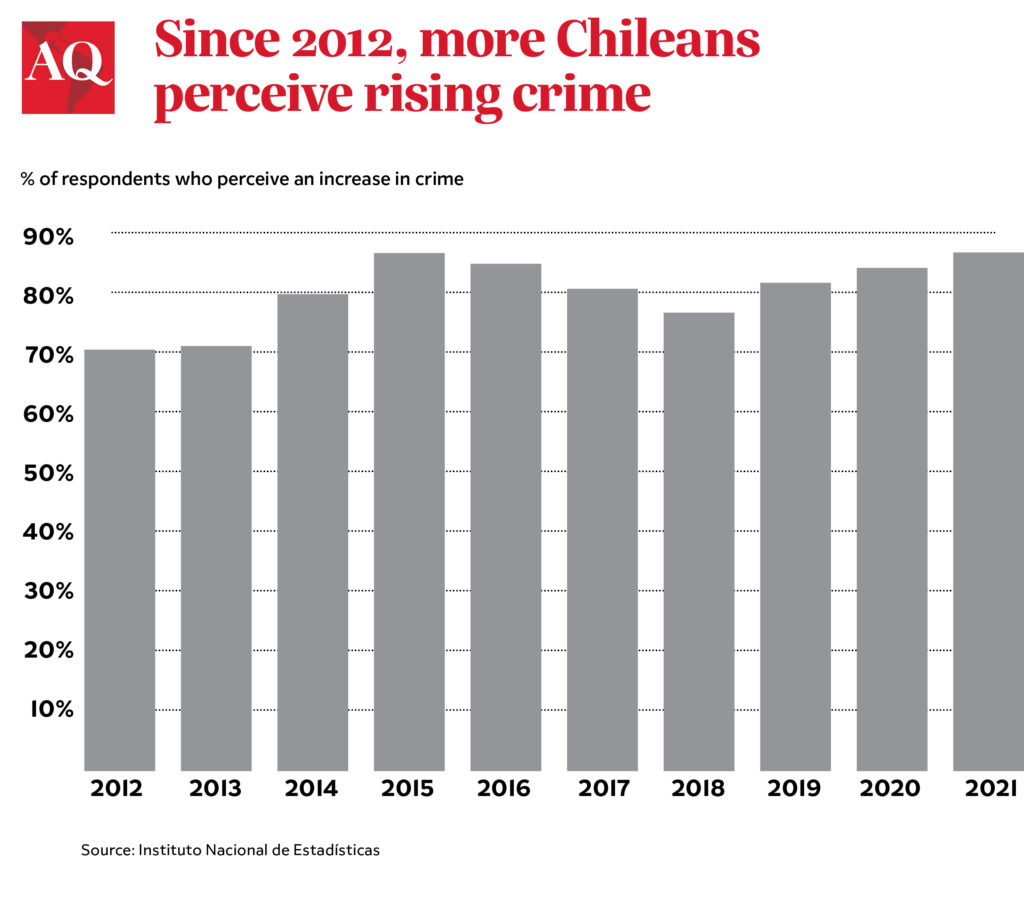

Tohá has extensive experience in politics but no strong background in security specifically. The conservative politician who foiled her bid for reelection in Santiago did so in part by portraying her as soft on student takeovers of schools—as she struggled to deal with perceptions of rising insecurity.

Her ability to make immediate progress is limited. But a key task will be taking forward reforms to Carabineros, Chile’s main police force, criticized for brutality from the left in recent years. This will involve a delicate needle-threading operation, as Tohá must combat abuses while also shoring up support for the force so they can take on the new security challenges the country faces.

“It’s going to have to be a combination of some Carabineros reform but also some short term measures to show the people they’re serious,” said Navia.

All in all, a truly imposing set of challenges lies before Tohá—but many longtime observers remain confident in her abilities, even keeping in mind that her task is not only a political one.

“She has a personal challenge ahead of her, too, because the president once criticized her,” said Bitar. “It’s necessary that both of them understand that the world is different (now). But I think Boric is capable of seeing this, and Carolina (Tohá) has the kind of story that lends itself to forging a new relationship between generations.”

For a Chile torn between past and future, much depends on the success of such an endeavor.