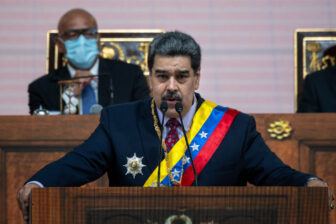

The growing power of the ELN guerrilla group has enormous implications if talks between Washington and Caracas continue to move forward. Latin America’s largest insurgency is ardently committed to protecting the regime of President Nicolás Maduro, making it an underappreciated stumbling block for any return to democratic rule and economic stability in Venezuela. It is already a potent obstacle to meaningful reform, and if it continues to metastasize, it will eventually jeopardize the regime’s very capacity to change course.

While details of recent U.S.-Venezuela talks remain secret, any grand bargain between the two governments would probably require Maduro to crack down on the ELN, Colombia’s enemy number one, given the close U.S.-Colombia relationship. Action against the ELN will likely remain a Colombian priority regardless of the outcome of its upcoming elections; in February the ELN organized an “armed strike” in Colombia that paralyzed various regions of the country for days, the third since 2019.

But Maduro and the ELN are increasingly co-dependent. Along the Colombia-Venezuela border—the hemisphere’s most volatile geopolitical fault line—the ELN is the Maduro regime’s first line of defense, actively containing potential threats both internal and external. It serves as a bulwark against potential incursions by the Colombian military and foreign mercenaries as well as domestic anti-regime political or insurgent organizing.

In a private interview, a former ELN commander told us that the group is now committed not only to undermining the Colombian state, but also to supporting Maduro, whose regime represents the political project the ELN has long aspired to establish in Colombia. Moreover, buoyed by its safe haven in Venezuela, the ELN is growing rapidly.

Founded in 1964 by students and radical Catholic clergy—and almost destroyed in the 1970s—the ELN was always overshadowed by the much larger FARC guerrilla group, even as it grew in the 80s and 90s through the extortion of oil companies in northeastern Colombia. Both had support from former Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, but when the FARC negotiated its disbanding through the 2016 Colombian Peace Accords the Maduro regime cultivated closer ties to the ELN, facilitating its rise.

Since 2016, the ELN’s forces doubled from an estimated 2,500 fighters to around 5,000. Over the same period, it expanded its area of operations in Colombia from 96 municipalities to 170. It has also expelled virtually all armed rivals in its area of operations in Venezuela, which has expanded throughout the extensive Venezuela-Colombia borderlands and well into the country’s interior, particularly along the Orinoco River and its tributaries.

The Venezuelan military now coordinates directly with the ELN, most recently in a joint assault against a FARC dissident group, according to a recent Human Rights Watch report. This coordination has become vital for the regime in the wake of the country’s dramatic economic collapse, during which the Venezuelan state retreated from large swaths of the border region and interior. The ELN has stepped in as a proxy, establishing a comprehensive system of rebel governance that stringently regulates social and political activity and extracts revenues from virtually all legal and illegal economic activities—including drug trafficking, contraband and illegal mining—in its area of control. It then shares these revenues with key regime players, including regional military commanders.

In this way, the ELN has become a key pillar of the Maduro regime itself, having played a vital role in the regime’s criminal evolution. To remain in power during times of reduced oil revenue, Maduro has relied on income streams generated by the ELN to maintain a clientelist system that ensures the loyalty of key players by cutting them in on illicit earnings.

The ELN has been so effective at developing illicit economies that even if Venezuela’s international negotiations resulted in pre-crisis levels of oil production and exports, much of the country would likely remain beholden to organized criminal networks run by the ELN and factions of the military. Quite simply, the ELN and these military factions are making far too much money to want to give them up. And even if Maduro were to turn on the ELN, it is highly doubtful that the Venezuelan military could expel it from the country given the ELN’s long experience with guerrilla warfare.

The ELN’s two most important commanders, Antonio García and Pablito, live in Venezuela and wield considerable influence. García is tentatively supportive of peace talks with the Colombian government, but Pablito, the ELN’s de facto military leader, is diametrically opposed. In recent years, ELN leaders participated in dialogue with successive Colombian administrations, but the most recent round of talks collapsed in January 2019 following a suicide car bomb attack against a police academy in Bogotá that left 23 dead.

A peace deal with the ELN is unlikely over the next few years. It will remain a major destabilizer in Colombia and a powerful player in illicit economies in Venezuela, so both Colombian interests and the on-the-ground reality indicate that any negotiations seeking meaningful democratic consolidation and economic stabilization in Venezuela will have to address the group.

But the ELN is making such negotiations less and less likely. The challenges posed by the ELN may encourage U.S. and international negotiators to limit potential talks to oil exports and the Russia question. If they chose this path, the ELN will be emboldened, as will the Maduro regime in its alliance with the group.

—

Larratt-Smith is an incoming professor of political science at the Tecnológico de Monterrey in Querétaro, Mexico.

Aponte González is a researcher of peace and conflict dynamics at Fundación Ideas para la Paz in Bogotá, Colombia.