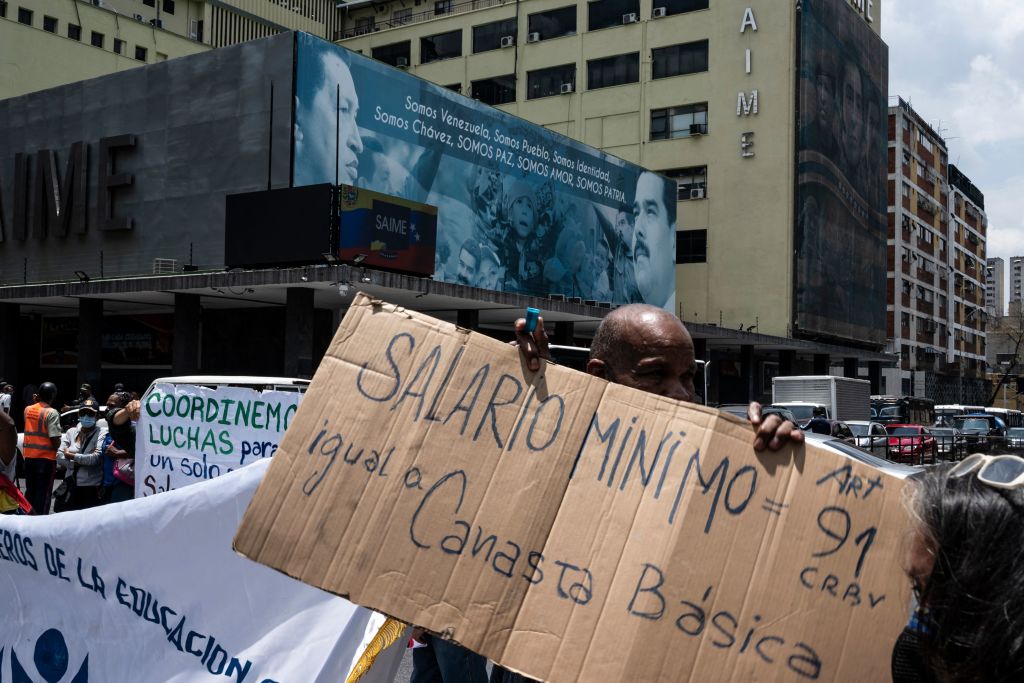

On Venezuelan Twitter and WhatsApp chats, there’s a specific genre of meme poking fun at the idea that Venezuela se arregló (“Venezuela is fixed”). As ad-hoc dollarization and economic liberalization have replaced the country’s hyperinflation and shortages, some claim that the worst is over when it comes to the country’s economic problems.

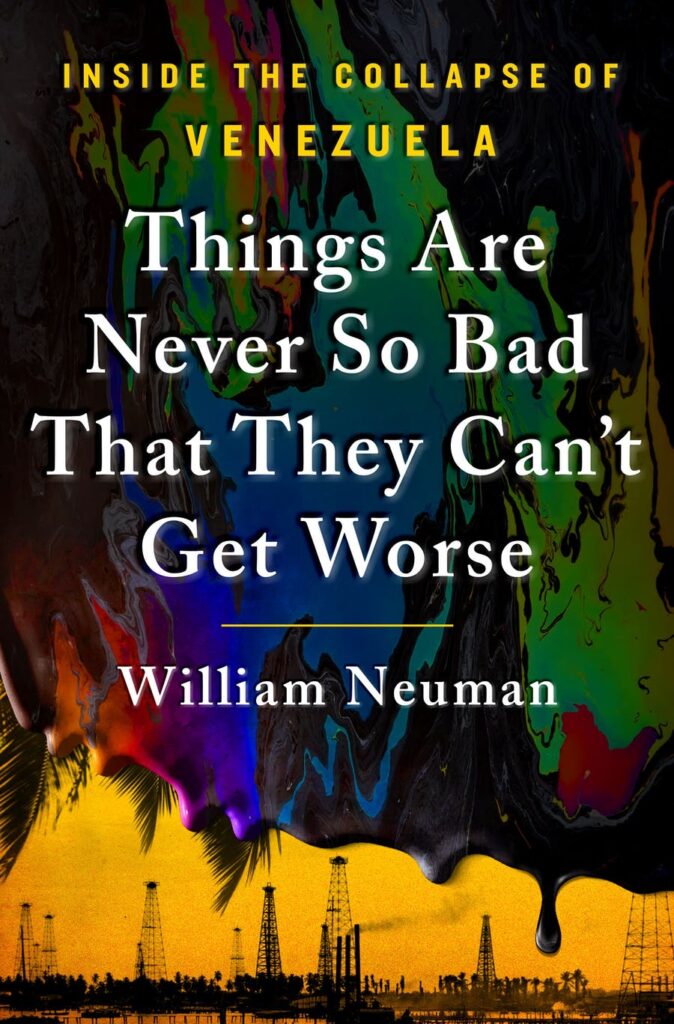

But Venezuela is far from being fixed. A recent local survey found that 95% of the population is poor, while 76% live on less than $1.20 a day. How did things end up this way? Things Are Never So Bad That They Can’t Get Worse: Inside the Collapse of Venezuela, a new book by journalist William Neuman, investigates how the country with the largest oil reserves in the world fell into a protracted crisis.

The former New York Times Andes region bureau chief’s book is an insightful survey of Venezuela’s downfall, offering valuable lessons about 21st-century populism, authoritarianism, economic mismanagement—and the failure of efforts to contain these forces. Neuman transforms Venezuelan tragedy into an approachable and rewarding book.

Things Are Never So Bad That They Can’t Get Worse: Inside the Collapse of Venezuela

by William Neuman

Macmillan

Hardcover

352 pages

Oil plays an outsized role in Venezuelan history—and in Neuman’s book, whose cover shows crude oil spilling across a field. “The history of Venezuela and oil flows through Mene Grande like the crude oil through the silver pipe”, he writes in the first chapter, referring to the first oil well drilled in the country. The book starts with a historical survey of the clientelistic structures that have defined the country since oil became its main export. Masterfully zooming in and out by mixing first-hand stories and expert voices, Neuman cites political scientist Terry Lynn Karl, whose 1970s studies of Venezuela “concluded that virtually everything in the country—its institutions and patterns of government, society and politics, and the economy—had been shaped by oil.”

In 1998, when Hugo Chávez was first elected, oil was at eight dollars a barrel—but that would quickly change. Fueled by China’s economic growth, oil prices rose for most of Chávez’s tenure until his death. As the author points out, the $768 billion in total oil sales from 1999 to 2013 was, adjusted for inflation, almost double the previous oil boom from 1974 to 1985. The author then catalogues the spree of unfinished rail lines, hospitals and expensive nationalizations. “Chávez’s socialism was all means and no production. It was showcialismo.” Neuman adds that Chávez “was a reality TV star before there was reality TV, a viral tweet before there was social media.”

Next came the bust—and the blackouts. The recurring, enduring shutoffs of electricity supply, especially outside the capital, symbolize the mismanagement of the largest oil boom in the country’s history. In Neuman’s book, the darkness of blackout is followed closely by the darkness of repression. In one of several moving first-hand accounts in the book, a constitutional lawyer who specializes in defending political prisoners opens up to the author about being tortured almost to death by Maduro’s special police force, the FAES.

As we near the present day, the book’s focus shifts to the efforts of the Venezuelan opposition and, later, Donald Trump’s White House to oust Maduro from power. Dealing with an unscrupulous regime that “determined to stay in power” (according to a “moderate” chavista interviewed by Neuman), this could not be an easy task. Yet, as the book describes, both the opposition and its main international ally oversold the likelihood of a quick transition to democracy. Through interviews with key opposition figures and senior White House and State Department officials, the author shows the hastiness and improvisation that accompanied many of the high-profile efforts to topple Maduro. Although Neuman makes it very clear that the main responsibility for Venezuela’s collapse lies with chavismo, he shows it is not the sole factor that explains today’s tragic impasse.

Reading Neuman’s book, I felt a sense of relief. We may not have the formula to restore democracy in Venezuela, but at least we have a better diagnosis. The first step to fix a problem is to identify its contours accurately. Neuman’s book does precisely that, and in a lyrical and captivating way.