This article is adapted from AQ’s latest issue on Latin America’s anti-corruption movement | Leer en español

PUCALLPA, Peru — No one in the Peruvian Amazon paid much attention at first when a low-level prosecutor was assigned a case involving missing government files.

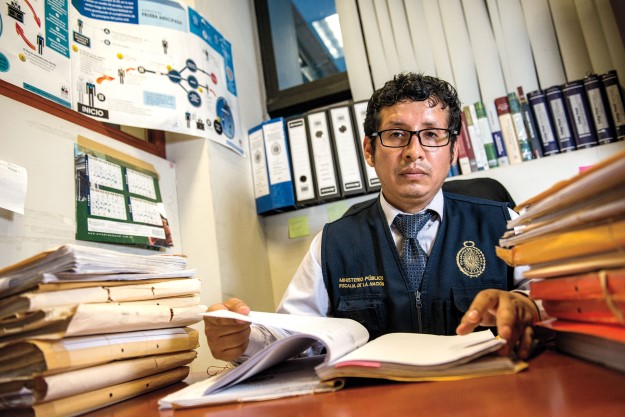

Wilber Huamanyauri Cornelio usually spent his days investigating thefts, murders and rapes, and his nights giving classes at a law school in Ucayali state, near the border with Brazil. The files, which had mysteriously vanished from a government office, contained potential evidence of a vast land trafficking scheme involving local officials.

The officials allegedly forged deeds to thousands of acres of Amazon forest, including vast areas claimed by native Peruvian communities as their ancestral land, and sold them to a murky web of companies. Much of the land has since been converted to the commercial production of cocoa and, most of all, palm oil — with palm trees, instead of native forest, stretching as far as the eye can see.

Palm trees have replaced the Amazon forest in vast portions of Peru | 360° view on | off

As Huamanyauri dug into the case, his phone started ringing with death threats. His car was scratched numerous times. A group of protesters appeared outside his office. His only assistant was dismissed for no apparent reason, forcing him to bring one of his students to help pro bono. Someone broke into his file cabinet — probably trying to get documents identifying a protected witness — leading Huamanyauri to buy a new cabinet with a better lock (which he paid for himself). He also built a makeshift glass and paper barrier to better isolate his office at the Public Ministry’s headquarters from his colleagues and visitors — many of whom now treat him like a pariah.

“I obviously knew the risks. But if I refused to investigate, I would be taking part in all this. Not prosecuting the case would be joining the corrupt ones,” said Huamanyauri, now 37, a man incessantly on the move and blinking his eyes behind a pair of dark-framed glasses.

Huamanyauri’s experiences show an often-ignored side of Latin America’s anti-corruption crackdown: What’s happening outside the bright spotlight of big cities like Lima, São Paulo and Mexico City.

The community of Santa Clara de Uchunya, three hours by boat and car from Pucallpa.

The community of Santa Clara de Uchunya, three hours by boat and car from Pucallpa.

Inspired by high-profile cases like Lava Jato, law enforcement officials deep in the interior are trying to root out the kind of systemic corruption that produces real-life consequences for their own communities— lost funding for clinics and schools, the contamination or destruction of local ecosystems and countless other ills. Laboring without much money, media coverage or protection, they face insurmountable challenges — and, often, the feeling of being totally alone.

Yes, it’s hard to build a Lava Jato in the Amazon. But through a combination of clever investigative techniques, a lot of recklessness and a bit of luck, some have made significant progress — sending powerful people to jail and trying, in fits and starts, to build the institutions and traditions they know are key to a lasting decline in impunity.

This is one such story.

Lost files, lost lands

The first allegations of land trafficking in Ucayali emerged in 2015, made by environmental prosecutors, local communities and NGOs. According to them, the agency responsible for issuing land titles — the Sectorial Agricultural Direction of Ucayali (DRAU) — was operating a well-oiled scheme to register new properties through fabricated documents. Peruvian law allows for small agricultural producers to request a property title under certain conditions, such as when they live and produce on the land. DRAU employees were accused of creating hundreds of fake petitioners to register properties, which were then sold to private companies.

In 2017, files that allegedly contained evidence of the forgery inexplicably disappeared — which was when Huamanyauri first got involved.

Despite the scope of the allegations, a probe by the Anti-Corruption Office of the Public Ministry in Ucayali never moved beyond lower-level DRAU staff. One of the employees questioned by prosecutors had used her son to forge a petition, allegedly following orders from above. Angry about taking the blame while her superiors got off free, she began recording interactions with colleagues.

In one of the recorded conversations, the director of DRAU, Isaac Huamán Pérez, seemed to imply that, with the files gone, the investigation wouldn’t lead anywhere. “Everything is under control,” Huamán could be heard saying.

The employee offered the tapes to Huamanyauri, and he made her a protected witness. A judge then issued a 18-month pre-trial arrest order against Huamán and another senior official at the agency — a move that was virtually unprecedented in Ucayali. (Both men have said they are innocent.)

Not coincidentally, that was also when the blowback began. Defense lawyers filed accusations against Huamanyauri for influence peddling and abuse of power, both of which were later dismissed. They also unsuccessfully tried to transform the case into an organized crime matter — a more serious charge against their clients, but one that would have put the case outside Huamanyauri’s jurisdiction.

Local media in Pucallpa turned against the prosecutor. Instead of portraying him as a hero — as media in big cities have often done with protagonists of major cases — Huamanyauri was accused of abusing his power and seeking fame and fortune on the backs of dedicated public servants. On one occasion, a group of protesters and cameras waited for him outside the Public Ministry’s headquarters.

“When I started working as a prosecutor … I noticed people in the Public Ministry referred to a group called ‘the untouchables’: wealthy and powerful figures,” Huamanyauri said. The group included many madereros, people involved in the timber industry, he said. They “were not subject to the law like all others — from a traffic ticket to homicide.”

“I never accepted this,” he said, “and I broke the rule in this case.”

A tribe under siege

In Santa Clara de Uchunya, an indigenous community of the Shipibo people, three hours by car and then boat from the state capital, you can see the real-world consequences.

Located between two sinuous rivers, Santa Clara has around 140 people living among a strip of wooden houses. A wall-less construction in the middle of the village is where adults gather to discuss collective matters. A few steps away, villagers can buy a beer and watch TV in an improvised bar with few chairs. Most of the time, electricity is on. And although one needs to travel a few hours to get cell phone coverage, several tribe members carry around phones.

Corruption has a tangible impact on Santa Clara de Uchunya, as foreign companies encroach on their land.

Corruption has a tangible impact on Santa Clara de Uchunya, as foreign companies encroach on their land.

The talk of Santa Clara these days is the surrounding land — much of which has been razed to plant palm trees, a global industry set to surpass $145 billion by 2026. Certain areas are guarded by armed men.

“We can’t enter the land where we used to hunt,” said Luisa González, who has spent all her 55 years in Santa Clara. She said the guards have on more than one occasion opened fire against members of the tribe.

Without access to hunting, the community needs to buy food in a nearby village, González and others said. “It is the destruction of our culture for future generations,” she said.

Luisa González fears the destruction of Santa Clara’s culture for future generations.

Luisa González fears the destruction of Santa Clara’s culture for future generations.

Proética, the Peruvian chapter of Transparency International, has investigated several land-trafficking schemes in Ucayali and elsewhere around the country. In a 2018 report, it said the land that has been razed near Santa Clara was acquired by companies registered to Dennis Melka, a Czech-American businessman. The Proética report also said Melka’s companies received lands as part of the trafficking scheme at DRAU.

In response to questions from AQ, Melka said the accounts related to him in the Proética report are “totally false … misleading and shameful journalism.” He cited several Peruvian court cases which have been dismissed, including allegations of falsified documents and usurpation.

The community, with the help of Ucayali’s Federation of Native Communities (FECONAU), has been battling in court to win the rights over the land for themselves. But one of the elders of the tribe, Manuel Silvano, said that even if the palm oil company leaves, it will take time to reverse the damage: “The palm trees are everywhere, and you can’t do much about that.”

Manuel Silvano, one of the elders of the tribe.

Manuel Silvano, one of the elders of the tribe.

Magaly Ávila, a project manager at Proética, has been in touch with both the villagers and Huamanyauri in an effort to help. She said “the lesson from Ucayali is that you cannot address the problem of deforestation without looking at corruption in local governments.”

The prosecutor and the tribe members share one thing in common, she added. “When you talk to them, you hear the same message: They feel abandoned by the state.”

For the president of tribe, Efer Silvano Soria, the outcome of the legal battle to recover nearby land seems uncertain.

For the president of tribe, Efer Silvano Soria, the outcome of the legal battle to recover nearby land seems uncertain.

Far from sight

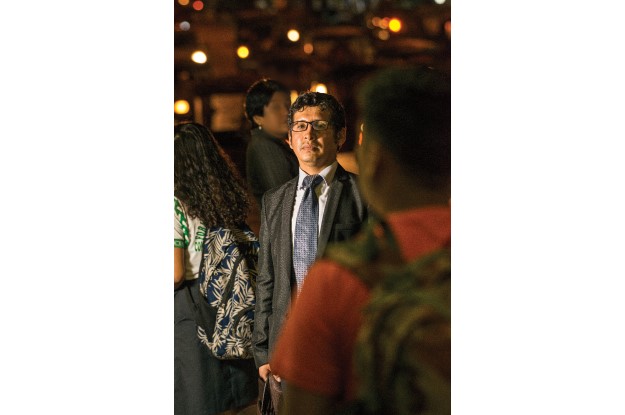

Indeed, Huamanyauri has struggled in recent months to keep his investigation afloat. It’s a different reality from Lima, which is going through an “anti-corruption spring,”in the words of former Congressman Sergio Tejada, who chaired the commission that investigated corruption in the second Alan García presidency (2006–2011).

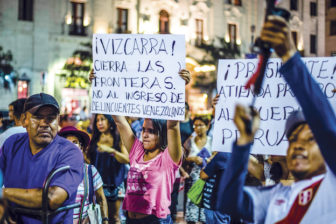

The Odebrecht probe has directly implicated all Peruvian presidents from 2001 to 2018, and many observers expect an investigation into another Brazilian construction company, OAS, to further expand the crackdown in coming months. The purge has also reached outside the realms of politics and business. Last year, a new scandal dubbed “the white-collars from the port” implicated high-ranking judges and prosecutors, caught on a police wire negotiating bribes and sentences. In January, then Attorney General Pedro Chávarry was forced out of office after trying to remove two senior investigators in the Odebrecht case.

President Martín Vizcarra — who came to power after President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski’s Odebrecht-related demise — has seized the opportunity and made the fight against corruption his signature policy proposal. Last year, 80% of Peruvian voters supported his proposed anti-corruption constitutional reforms in a national referendum. Vizcarra is now pushing for a political reform bill in Congress, which includes strict limits to immunity for elected officials.

Meanwhile, corruption is the talk of town in the capital. From the main pages of newspapers’ Sunday editions to prime-time TV, the crackdown on graft and Vizcarra’s reforms dominate the political conversation. Nonfiction books on corruption are a new genre, prominently displayed in Lima’s bookstores.

Several factors allowed for the “anti-corruption spring” to flourish — at least in big cities. Peru has a new generation of top prosecutors without the political ties of the Public Ministry’s old guard. Tejada also believes that, in the case of Odebrecht, investigators were smart in starting with relatively low-hanging fruit — politicians with less influence, such as former President Ollanta Humala — to build momentum before going after more powerful players.

In faraway Ucayali, however, law enforcement agencies and courts are partially filled with political appointees and very exposed to private interests, including from madereros or the palm oil industry. Prosecutors and police are chronically underfunded. Investigative journalism is almost nonexistent and local media lacks independence from important business leaders or party bosses. More broadly, the region is significantly behind the capital in terms of socioeconomic development: GDP per capita in Lima is three times higher than in Ucayali.

Timber producers (madereros) near Santa Clara de Uchunya. Ucayali is the most deforested state in Peru.

Timber producers (madereros) near Santa Clara de Uchunya. Ucayali is the most deforested state in Peru.

There are also worrying signs that the scale of corruption in Ucayali and the rest of Peru’s interior might have increased in recent decades. Starting in the 1980s, Peru began an erratic decentralization process that, in many ways, increased opportunities for corruption in the countryside. One example was the power to assign land titles, which shifted from authorities in Lima to the DRAU in Ucayali and similar regional agencies. But these local administrative bodies lacked institutional and human capacity to perform the new tasks.

“The decentralization process began while Peru was fighting inflation crises and the Shining Path guerrillas. Then, in the early 1990s, came fujimorismo. The context was extremely difficult,” argues Paula Muñoz, a political scientist at Universidad del Pacífico and a member of the High Commission for Political Reform. According to Muñoz, today the regions have substantial governing power and increased tax revenue, but still insufficient oversight and low institutional capacity — an explosive mix for corruption, she said.

In a white paper for preventing corruption, the “National Integrity Plan,” the Vizcarra administration listed decentralization as one of the top challenges. “We recognize that there has been an absence of the state in various subnational levels and this has led to grotesque levels of corruption and crime,” said the Peruvian secretary for public integrity, Susana Silva Hasembank. “We haven’t implemented a well-thought plan to transfer capabilities and responsibilities.”

Silva believes that steps like strengthening a career civil bureaucracy, less permeable to political interference, and justice reform are key to fighting corruption in regional governments. The secretary also wants to implement ideas from the private sector, including creating “chief public compliance officers” inside local government agencies. But she recognizes that any progress will come slowly.

For his part, Huamanyauri is planning to expand the investigation, going after other members of the Ucayali government who masterminded and executed the corruption scheme. But by doing that, the probe will become a criminal case with more than three defendants and a prosecutor specialized in organized crime will have to replace him.

Huamanyauri in the streets of Pucallpa.

Huamanyauri in the streets of Pucallpa.

Huamanyauri fears his colleagues in the Organized Crime Office in Ucayali might simply stop the investigation altogether. Or worse: they could overturn his decisions, freeing the DRAU director and senior staffer, and go after him with misconduct and abuse of power allegations.

The best solution, says Huamanyauri, would be to push the case to prosecutors in Lima. According to him, private companies that benefited from the Ucayali scheme are registered in the capital, which gives Lima investigators jurisdiction over the matter.

“I know they are going to do a serious investigation,” Huamanyauri said. “They are competent and have no ties to people here. I fear if the case stays in Ucayali.” Indeed, the best thing for the case in the long run might be if it leaves the Amazon altogether.