It may have taken 20 years for Mercosur and the European Union to reach an agreement on a trade deal. But since the accord, the South American block seems ready for more.

The surprise agreement has justifiably attracted global attention, but initial reactions have glossed over a crucial element: Though hugely significant on its own, the deal might ultimately be more important as a steppingstone to a series of additional trade agreements for South America’s two biggest economies.

That would be a departure for Mercosur. Historically, the customs union, established in 1991, has failed to link its members to global value chains. Though it successfully integrated member economies, and moderated the historic Argentina-Brazil rivalry, it has until recently been largely a protectionist architecture.

Now, however, the EU deal is poised to open doors to a range of Mercosur agreements.

Bolsonaro, the rotating Mercosur leader and a close ally of President Donald Trump, followed the EU-Mercosur announcement by proposing a free trade agreement with the United States.

For his part, Argentina’s production minister reiterated Mercosur’s commitment to pass all of the trade deals already under negotiation. “The agreement with the EU is going to provide order to the economy and will be the key to modifying this outdated vision of international trade,” Horacio Reyser, Argentina’s top diplomat for international trade, said. “Integration with the world is one of our primary goals as a government.”

Brexit might give Mercosur yet another opportunity to build on recent momentum. Should Britain leave the EU, it will be eager to reestablish preferential market access. Though Prime Minister Boris Johnson has pinned his hopes on a free trade deal with the United States, a Mercosur agreement would be far easier, as the British helped negotiate the EU-Mercosur deal.

Even before the historic announcement in Japan, Mercosur negotiators were in talks with Canada, the European Free Trade Association, Singapore and South Korea, which would give access to economies that together account for 4% of global economic activity.

The EU-Mercosur agreement will likely turbocharge those negotiations. As the milestone deal pries open Mercosur’s closed economies, it will build momentum for similar agreements with smaller economies. Moreover, because the Mercosur deal includes high standards for liberalization and regulation, it will facilitate pacts with countries that impose less onerous conditions.

The deal is a leap into the unknown for the South American trade bloc, carrying both opportunities and risks. The EU, for example, is known for its rigorous standards regarding environmental, social, labor, health and safety rules. Reaching those standards will not be easy for Mercosur; after all, its competitiveness is based in part on lower prices that reflect lower regulatory standards than in more advanced economies.

The trade agreement will force Mercosur firms to compete based on investment in research and development that increase quality and productivity. That is a tall order, given the disadvantages South American firms endure, such as poor public infrastructure. But the sacrifices of synchronizing regulatory standards will pay off, giving Mercosur exporters not only access to the EU, but to other markets with compatible requirements.

By all accounts, the current leadership in Argentina and Brazil are up for the challenge.

Decades of import substitution and stalled market reforms in the 1990s left Argentina and Brazil with some of the highest tariffs rates in the world. As a result, their industrial sectors failed to adapt to foreign competition, especially given persistently high local labor and logistics costs.

Historically, Chile has been South America’s trade leader, with 26 agreements covering 87% of global GDP. As for Latin America’s trade blocs, until last month it was the Pacific Alliance – comprising Chile, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru – driving the region’s global economic integration.

But seemingly all at once, Mercosur is trying to catch up.

However, the moment could fizzle fast if critics in Europe or South America scuttle the EU-Mercosur pact.

Indeed, the fate of the EU-Mercosur trade deal is uncertain, given the rise of nationalist and populist forces in Latin America and Europe, which reflects a global phenomenon.

In the 2016 U.S. election, both the left and the right assailed free trade agreements, and Trump promptly pulled out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership. In Argentina today, the leading opposition candidate in the October presidential election, the Peronist Alberto Fernández, said the EU-Mercosur deal was “nothing to celebrate.” His party’s candidate for Buenos Aires governor, Axel Kicillof, the former finance minister for Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, went further, labeling the agreement a “tragedy.”

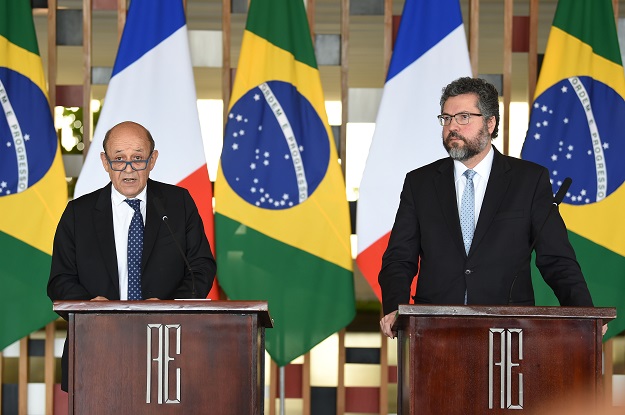

Industrialists in Argentina and Brazil could also try to thwart congressional approval, while agricultural interests in Europe might introduce further roadblocks. Bolsonaro may have created an extra hurdle to the accord by cancelling a meeting with France’s Foreign Minister Jean-Yve Le Drian to have a haircut – live on social media.

But so far, those in power in Europe and South America appear steadfast. The EU’s trade commissioner, Cecilia Malmstrom, has heralded the pact as an “historic moment,” saying European and South American leaders were “doing the world a favor” by standing up to protectionism.

To Bolsonaro, the deal is “one of the most important economic agreements of all times.” Indeed, it promises greater access to Europe’s vast market (accounting for nearly 20% of global GDP) for the competitive agricultural exports from Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay, while creating challenges for the region’s long-protected manufacturers.

Macri is also closely associated with the agreement. His active involvement is arguably most critical, given his easy relationships with both nationalists like Bolsonaro and Trump and liberals such as French President Emmanuel Macron and the German chancellor, Angela Merkel.

The enthusiasm in Brasilia and Buenos Aires – and dependable support in Paraguay and Uruguay – give the EU-Mercosur deal a good chance at passage. That would give reason to celebrate, but little time to reflect on the achievement, as Mercosur’s trade negotiators, once an endangered species, rush to pursue a cascade of trade talks throughout the world.

—

Gedan, a former South America director on the National Security Council, is the senior adviser to the Latin American Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and an adjunct lecturer at Johns Hopkins University. Saldías is a Wilson Center researcher.