This article is adapted from AQ’s print issue on peace and economic opportunity in Colombia | Leer en español

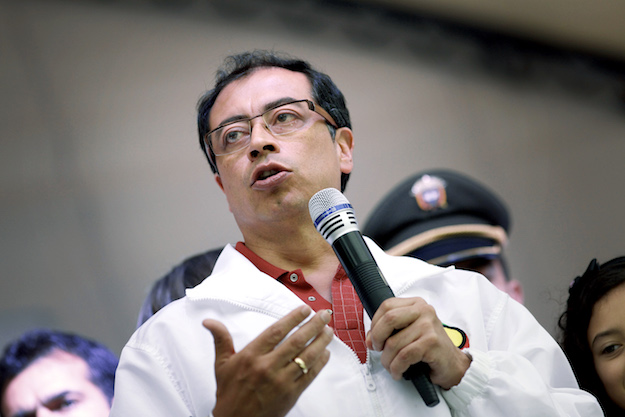

Short, slight and bespectacled, prone to spending hours debating brainy topics like Latin American geopolitics, Gustavo Petro hardly strikes the figure of a firebrand.

But with a unique mix of quiet self-assurance and heated oratory, the one-time guerrilla leader and former mayor of Bogotá has rallied many Colombians with his denunciations of corruption and inequality. Colombia is primed for his message and for his promise to shake up the status quo; Petro’s well-timed run has landed him at or near the top of the polls for Colombia’s 2018 presidential election.

He is also feared by many in the business community, who regard him as an arrogant latter-day Hugo Chávez and have sounded alarm bells as they’ve seen him maintain a steady following. But the onslaught has only made him stronger among his supporters.

“The more I am attacked, the more support I get,” Petro told AQ in a recent interview.

“When you dedicate yourself to uncovering the hypocrisy of politics in this country, you touch many interests.”

Colombians have often flirted with leftist presidential candidates, but these politicians have seldom fared well, and never won, in part because of their perceived support for unpopular guerrilla groups. But following last year’s peace deal with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), which ended a five-decade-long civil war, that taboo may have been lifted.

As a result, many Colombians could feel inclined to vote for any candidate who can tap into the strong anti-establishment mood. Two-thirds of adults believe the country is currently on the wrong track, according to a nationwide Opinómetro poll published in September by Datexco. Outgoing President Juan Manuel Santos had an approval rating of just 25 percent, while approval of the political class in general tumbled to just 7 percent — a third of its level in February.

The malaise may contrast with the rosier international image in recent years of a Colombia that buried many of its demons with the FARC deal, and has seen urban violence fall precipitously since the days of Pablo Escobar and the cartels of the 1990s. But anger over a wave of corruption scandals, the quality of health care, unemployment levels, and an economy that has struggled with low oil prices and some policy missteps, are among the most important issues for most voters.

Petro believes he’s prepared to address those concerns, and more.

He calls himself a “progressive leftist,” not a Marxist — and laughs off the comparisons with the late Chávez. “I have more in common with Pepe Mujica,” Petro said, referring to the much-loved former Uruguayan president, who belonged to his country’s Tupamaro guerrillas. “But Pepe Mujica doesn’t scare anyone, so they invented” the comparisons with Chávez and the late Fidel Castro that the Colombian right has labeled Castro-Chavismo.

Petro said as president he would target Colombian elites’ hold on power, but also work to prevent climate change and find new economic development models that do not rely so extensively on extractive industries like oil. While mayor he concentrated many of his policies on the low-income population of Bogotá’s sprawling slums, guaranteeing access to potable water, subsidizing transportation, and recognizing the labor of informal recyclers. He focused on reducing the wealth gap in the capital of a country that, by one measure, has the worst inequality in Latin America behind only Haiti.

“My vocation is to change Colombia, to make it more equitable, to seek to include those who have been excluded for so many decades,” he said.

Petro confronts police during a 2004 march in Cartagena.

Petro confronts police during a 2004 march in Cartagena.

Few Colombians would argue with those goals. But Petro spurs as much — or more — rejection as he does interest. In a poll taken at a recent convention of business leaders, only 1.5 percent said they would vote for Petro. Overall, 56 percent of respondents in the Opinómetro poll said they had a “negative image” of him — one of the worst ratings in the field.

That divisive, love-him-or-hate-him image has a lot to do with his militant past.

From guerrilla to politician

Petro showed his rebellious nature at a young age, once driving a priest out of town after publicly denouncing that he had a wife and children.

By age 17, Petro joined the urban guerrilla April 19 Movement. Better known as M-19, members defined themselves as more reformist than revolutionary, closer to the teachings of South American liberation hero Simón Bolívar than those of Marx. Petro took the nom de guerre “Aureliano” after the main character in Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Soon after joining, Petro caught the attention of veteran rebels like Ricardo Rosanía, who called him “a promising youth.” Petro rose quickly into the group leadership’s political arm, and said he never participated in armed action.

He was already an active, but clandestine, member of the M-19 when he was elected as ombudsman of his hometown in 1981. His double life caught up with him in 1985 when he was arrested by the army for possession of weapons — which he said were planted — and tortured for four days in the army’s horse stables.

“I was in prison, alone and tortured,” he said. “It was hard.”

During Petro’s 16 months in prison, the M-19 staged its bloodiest attack, holding the Palace of Justice under siege in 1985 and keeping some 300 people hostage, including the Supreme Court magistrates. By the time government troops took control of the building 27 hours later, more than 100 people were dead or missing.

That attack remains infamous even by Colombian standards — and many here still refuse to forgive the M-19 or its former members. But they were also one of the first guerrilla groups to demobilize and seek a role in traditional politics, doing so in 1990. Petro won a seat in Congress, starting a long legislative career that saw him win the most votes of any representative in 2002.

Petro with President Santos at an event commemorating the demobilization of the M-19.

Petro with President Santos at an event commemorating the demobilization of the M-19.

That year, Petro found another calling: as one of the leading challengers of Álvaro Uribe, whose two presidential terms from 2002 to 2010 saw a dramatic decline in violence but also widespread human rights abuses. Petro presented Congress with evidence of collusion between politicians and paramilitary leaders that implicated the president and his allies. They fought back, but the charges stuck, and many of those Petro accused were eventually convicted.

This crusade led to death threats, and Petro took to sleeping with an assault rifle under his bed.

Through it all, he has brandished a sharp tongue. “I don’t like diplomacy,” he said. “I tell things the way I see them.”

Dangerous for the country?

These days, Petro surrounds himself with old companions from his guerrilla days, and prefers books to loud parties. His expansive personal library, with titles in Spanish and French, include volumes such as Marxist Theory Today, In the Time of Catastrophe and Democracy and Social Transformation.

During Petro’s first run for president in 2010, he managed more than 1 million votes. That wasn’t good enough to make the second round, which Santos eventually won in a landslide against a more moderate leftist, Antanas Mockus. But Petro was widely regarded as having a bright future.

Since then, two controversies have won him additional fans and enemies.

The first is his relationship with Chávez, and his successor Nicolás Maduro, as Venezuela slid into dictatorship and humanitarian crisis.

Prior to Chávez’s election as president in 1998, Petro was captivated by the Venezuelan’s ideals, shaped as they were by Bolívar. But Petro said he reconsidered once he saw Chávez’s authoritarian streak, and realized Venezuela’s 21st century socialism looked a lot like Cuba’s failed 20th century model. He also criticized Chávez’s close relationship with the FARC, a group Petro considered radical and responsible for gross human rights abuses.

Still, when Petro attended Chávez’s funeral in 2013, he wondered aloud, “Why did I distance myself from him?” recalled Hollman Morris, a Bogotá city council member who went along.

These days, critics see a troubling ambiguity in Petro’s views on Maduro. While he has condemned the “crushing of dissent” in Venezuela, Petro also challenges Colombians to focus first on their own problems, including the killing of thousands of young civilians in the mid 2000s to boost the army’s body count in the fight against FARC, and the persecution and illegal surveillance of opposition politicians, including himself.

“Criticizing Venezuela is a way for Colombians to hide our own truths from ourselves,” he said.

The other thorny chapter is Petro’s time as mayor of Bogotá.

As a congressman and candidate, Petro was open to opinions, and enjoyed debating politics and policies. But in 2011, when he took office in the Liévano Palace, Bogotá’s city hall, he began to show an autocratic side, said a former collaborator who did not want to be identified because he still considers Petro a personal friend.

“He didn’t want to hear people who contradicted him,” the collaborator recalled. “He just stopped listening. It was his way of showing the world, ‘I’m the boss here.’ ”

Even close supporters rejected this attitude. Antonio Navarro, a respected leftist politician whom Petro named his chief of staff and who had been his commander within the M-19, resigned just a few months in. More than two dozen others named to different secretariats in the city government followed suit.

Surrounding himself with yes-men, mostly from his M-19 days, Petro took on the political and economic powers that controlled Bogotá, said Rosanía, the former guerrilla who later became one of Petro’s advisors.

“He is a man who seeks rupture,” he said.

Beyond policies and ideology, this is why business leaders fear Petro: They see him as a catalyst for divisions in Colombian society. He’s “dangerous for the country,” said the CEO of a manufacturing firm who asked to remain anonymous because he fears retribution if Petro comes to power.

Time for change

While still mayor, Petro allowed the contracts of private garbage collectors to lapse in a bid to revamp the system and include informal recyclers. Before he could implement a new arrangement, piles of garbage accumulated on street corners, sparking an immense public outcry.

The problem was mostly resolved in three days, but a year later, Colombia’s ultra-conservative inspector-general used the incident to depose the mayor and ban him from public office for 15 years. The former inspector-general, Alejandro Ordóñez, argued that Petro had violated the principles of the free market and put public health at risk.

Informal recyclers came out in support of Petro after he was removed from the mayor’s office.

Informal recyclers came out in support of Petro after he was removed from the mayor’s office.

Petro claimed that his removal from office was in retaliation for his progressive administration, which had also banned bullfighting, tried to curb property developers and defended gay rights. Taking to the balcony of the Liévano Palace, Petro gave impassioned speeches over three days to tens of thousands. The crowd included supporters, but also critics of Petro who disagreed with his removal.

“People may not have been supporting Petro but they respect democracy and were defending that,” said Morris, who was then the manager of Canal Capital, a city-owned television station that broadcast the protests and speeches live.

Petro fought the decision in court and won; after a month out of office he was reinstated. Emboldened, Petro continued to rankle the ruling class: He announced plans to build social housing projects in one of Bogotá’s most upscale neighborhoods and restricted construction permits to curb urban sprawl.

For Petro, the “balcony days,” as his supporters call them, were the pinnacle of his career, a moment when he got the praise he craves while railing against the system. Petro now believes the inspector-general did him a favor.

Jaime Rolón, 30, who teaches vocational training in some of Bogotá’s poorest neighborhoods, is one of Petro’s supporters; he recently signed a petition to allow Petro to run for president as an independent in the 2018 elections, even though he believes he won’t win.

“I signed to see if things change in this country once and for all,” he said. “We’re tired of the same people.”

Petro may still face legal obstacles to becoming a candidate, even if his campaign comes up with the 400,000 or so signatures needed to register. Opposition lawyers believe a ruling by Bogotá’s comptroller’s office, which fined him $80 million for damaging the city’s finances when he subsidized public transportation, should prevent him from holding public office. Petro and others dispute the view, though a final judgment on whether he can run is pending.

Whether or not he’s the one at the helm, Petro said the country’s future hinges on the next president’s ability to implement the peace agreement with the FARC and tackle corruption, both of which would take a leftist from outside the traditional political establishment.

“If (progressive forces) don’t win, Colombia could fall into a new spiral of violence.” Petro said, in a stark warning that will likely further enrage his opponents — and rally supporters.