This article is adapted from AQ’s latest issue on Latin America’s anti-corruption movement | Leer en español | Ler em português

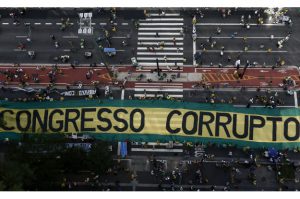

About five years ago, something strange started happening throughout Latin America: Powerful people began going to jail for corruption. Presidents, senators and business leaders long regarded as untouchable were suddenly being held to account for their role in mind-blowingly huge scandals with names like Lava Jato (“Car Wash”) and La Línea (“The Line”).

This was widely portrayed, by this magazine and many others, as a story of progress. Many credited the spread of democracy since the 1980s, which has helped give rise to more independent judicial institutions. Of course, some countries (Brazil, Peru) were advancing faster than others (Mexico, Venezuela). But many saw a once-in-a-generation opportunity to substantially reduce the impunity that has always been one of Latin America’s biggest curses, contributing to poverty, inequality and numerous other ills.

Today, that hopeful story is at risk. Several recent cases illustrate why, without change, the anti-corruption drive will fall well short of the transformation many dreamed of.

In some cases, elites have conspired to undermine, or even destroy, the gains of recent years. This was the case in Guatemala, where authorities dismantled the UN body investigating corruption and blocked a popular former attorney general from running for president. Colombia’s Congress failed to approve any of the anti-corruption reforms endorsed by almost 12 million people in 2018 — a greater number than voted for the current president. Entrenched powers in Brazil, Peru and Mexico have attempted to limit the scope and powers of investigations.

Elsewhere, the law enforcement community can blame itself. The leak of private messages between former Lava Jato judge (and current Brazilian justice minister) Sérgio Moro and prosecutors pointed to possible bias and procedural violations in the region’s most iconic and sweeping investigation. Others have abused the use of pre-trial detention. These issues have allowed defendants to claim they are the victims of political witch hunts — and a growing percentage of the public is agreeing with them, according to polls.

This issue of AQ contains a clear-eyed overview of where things stand, and points to ideas to get back on the right track. Above all, it is necessary to move past the infatuation with superstar prosecutors, and focus instead on reforms and laws that will strengthen institutions. This is the best way to stop desperate politicians from sabotaging investigations — and ensure that law enforcement itself obeys the rules. The ends cannot justify the means for either group. As this issue also shows, there are too many brave people working to advance the rule of law — everywhere from the Peruvian Amazon to Mexican investigative journalism — for the crackdown to stop now.