In 1829, Chile’s legislature named José Joaquín Vicuña as the country’s new vice president. While this may sound like the start of the world’s most boring history lesson, Vicuña was a sufficiently objectionable figure that his appointment triggered a coup – and then a two-year-long civil war that left some 2,000 people dead.

The experience was traumatic enough that Chile’s Constitution of 1833 eliminated the role of the vice presidency entirely – and the country has not had one since, leaving the interior minister first in the line of succession. Somewhat similar dynamics led Mexico to abolish the vice presidency in the wake of the Mexican Revolution, after the last person to hold the job was assassinated. These are the exceptions in today’s Latin America, but here’s one more little-known fact: As recently as the 1940s, only about a third of the region’s countries had a vice president, and they seemed to get along just fine.

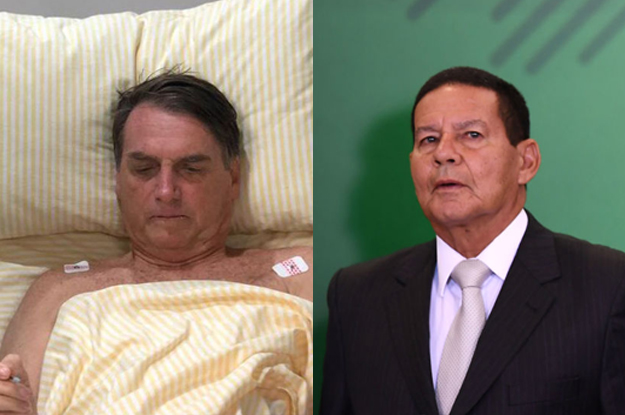

I was reminded of this obscure history this week, as Jair Bolsonaro struggled to fulfill his presidential duties from a hospital bed in São Paulo. Following a traumatic, nine-hour surgery to remove a colostomy bag he had worn since an assassination attempt last September, Brazil’s president was back at work just 48 hours later, holding video conferences with ministers and signing documents from his hospital bed while shirtless and covered with medical monitors.

This appears to have been ill-advised. Over the weekend, Bolsonaro’s doctors reportedly reprimanded him for talking too much, warning it could lead excess gas to collect in his abdomen and prevent scarring. They also recommended he stop following congressional proceedings on television. Then, on Monday, a major setback: The president would be in the hospital for at least another week, and was temporarily banned from speaking at all.

A reasonable outsider might ask: What was the big rush? Why not just let the vice president handle his duties for a few extra days, as the Constitution allows, and focus on a proper recovery? But the answer was clear. Barely a month into his presidency, Bolsonaro has a severely strained and possibly broken relationship with his number two, retired general Hamilton Mourão. Earlier in January, when Mourão assumed presidential duties during Bolsonaro’s week-long trip to Davos, he gave multiple interviews and statements conspicuously at odds with his boss’ views on everything from loosening gun controls (pointless, he said) to moving Brazil’s embassy in Israel to Jerusalem (might not happen, he told Arab diplomats). In perhaps the ultimate diss, Mourão even took to Twitter to compliment the press – which Bolsonaro frequently rages against as “fake news” – for their “dedication, enthusiasm and professional spirit.” No wonder Bolsonaro was so hesitant to hand power back again.

On one level, Mourão’s rhetoric illustrates a very real ideological split within Bolsonaro’s government. There is the so-called anti-globalist wing, led by Foreign Minister Ernesto Araújo and Bolsonaro’s own son Eduardo, that is keen to remake Brazil’s foreign policy to bring it closer to Washington, Donald Trump and nations with “Christian values” – and take distance from China and the Arab world. Mourão represents a powerful faction made up largely of former military officials, who account for about a third of Bolsonaro’s cabinet. They are not a monolith, but they generally favor a more pragmatic approach to foreign policy, noting for example that China is Brazil’s biggest trading partner. Many couldn’t care less about the social issues – “gender ideology,” “cultural Marxism” and so on – that tend to animate Bolsonaro’s hard core base.

This has led to an unusual dynamic in which moderate-minded Brazilians are counting on the military to prevent a more radical turn. The most glaring example was when Jean Wyllys, Brazil’s most prominent LGBT congressman and longtime antagonist of Bolsonaro’s, declared last month that he was resigning his seat and fleeing the country after receiving numerous threats. Bolsonaro posted celebratory messages on Twitter (“It’s a great day!”), while Mourão somberly noted that “anyone who threatens a congressman is committing a crime against democracy.” This prompted an outpouring of I-can’t-believe-I’m-praising-Mourão messages on Twitter and elsewhere. One friend from the São Paulo academic world texted me: “It’s incredible, but this could be the man who saves Brazilian democracy.”

Perhaps, but there may also be a deeper, worrying trend at work. Since Brazil’s last dictatorship ended in 1985, three of five vice presidents have ascended to the top job – because of one fatal illness and two impeachments. That’s a stunning 60 percent, for those keeping score at home. In the most recent case, Michel Temer openly schemed against Dilma Rousseff, complaining in a letter that she had made him a “decorative vice president” – and then leading the effort to impeach her in 2016. In this context, some wonder whether Mourão is driven by genuine policy differences – or if he is already openly auditioning for his boss’ job. “He’s a traitor,” one person close to the government told me this week. The split is so public that even Steve Bannon, the American nationalist leader who is close to the Bolsonaro family, weighed in in an interview published on Wednesday, calling Mourão “not useful” and “a guy who steps outside of his lane.”

Which leads to the question of whether Brazil can handle having a vice president at all. Maybe the position itself is inherently destabilizing, especially in a country with a patchwork of several dozen political parties that forces odd and ultimately brittle coalitions. Don’t laugh – this was precisely the conclusion of a recent paper by Leiv Marsteintredet and Fredrik Uggla, two Scandinavian academics, in what they billed as the first major study of the Latin American vice presidency. They found that Latin American countries in which presidential candidates are compelled to nominate a running mate from outside their party are “almost three times as likely to suffer interruptions such as coups and impeachments” than those in which the ticket is more homogenous. The authors leave open whether the vice presidency is the cause, or a symptom, of this instability. But in the context of Brazil’s record, it sure raises a few eyebrows.

Do recent events in Brazil approach the trauma of Chile in 1829, or Mexico in 1913? Maybe not. And of course, trying to make any structural changes in the current political climate would be even more destabilizing. But it’s worth wondering if Brazil might be better served in the future by a model that provides less incentive for intrigue and rebellion. In his infamous letter to Rousseff, Temer himself complained: “I’ve always been aware of the absolute distrust you and your team have shown me … a distrust that is incompatible with what we’ve done to maintain the personal and party support for your government.” But maybe it wasn’t the Rousseff-Temer partnership that was incompatible; maybe it was the whole model.