This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on migration

LIMA — At the Polvos Azules flea market in downtown Lima, there are so many Venezuelan vendors in row seven that some call it Little Caracas.

“I’ve been lucky — in Peru, I eat three meals a day,” said Enrique Callvit, 24, who fled Venezuela on a Friday in 2018 — and found a job selling shoes here by the following Tuesday. A few stalls down, Ian, 20, said he saves enough money to send $25 to $50 a week home to his family. His main disappointment: he hasn’t been able to practice baseball as much as he likes. “You know how Venezuelans are, we always want to play,” he said with a laugh. “But the truth is I can’t complain.”

Indeed, the mood here was generally positive — until I ran into Maria, one of the few Peruvian vendors left on row seven. She asked if I was American. “Ahhhh, Trump!” she said with an approving smile. “I like the way he handles immigrants. In Peru, I think we’re too good, too kind.” I asked if she’d had trouble with her colleagues. “No, no, these are fine,” she replied with a sweep of the hand, lowering her voice a bit. “But there are too many criminals. I hear Maduro lets them out of prison,” she said, referring to the Venezuelan dictator, “and they come here to steal and kill.”

Sadly, such sentiments are increasingly common throughout Peru — and much of the region. After years of welcoming an unprecedented wave of migrants from Venezuela and elsewhere, many Latin Americans now say in polls they are tired of rising crime and a perceived competition for jobs, especially in the informal economy — and they want the influx to stop. Even before the coronavirus pandemic forced borders to close in March, several governments in the region were taking aggressive steps to stem the flow of migrants.

Peru’s story illustrates how much has changed. When the exodus from Venezuela began to spike in 2017, the government of Pedro Pablo Kuczynski extended a temporary work permit to arriving Venezuelans. “It was important to make a real gesture, not just symbolic, that we believe in freedom, in the movement of people,” Kuczynski told me. Many called it the most accommodating migration policy in South America, and the response was enormous. In 2018 alone, some 500,000 Venezuelans entered Peru. Today the total number of Venezuelans in the country is estimated at around 860,000.

To try to fathom the political and social impact of this, remember how a roughly similar number of Syrian refugees roiled politics last decade in Germany — and then consider that Peru, with 32 million people, has a little more than one-third of Germany’s population. Venezuelans speak the same language as Peruvians, of course, but there are important cultural differences between the Caribbean region and the Andes. Integrating in Peru is much harder than in Colombia, many Venezuelans who lived in both places told me. “(Peruvians) think we’re too loud,” Johny, 31, told me. “And nobody here likes arepas, either.”

Nonetheless, most Venezuelans were quick to say they feel welcome most of the time. “The Peruvian state and the Peruvian people have shown solidarity,” said Carlos Scull, the ambassador to Peru for Juan Guaidó, whom Lima recognizes as Venezuela’s legitimate leader. Many Peruvians are still grateful to Venezuela for receiving thousands of their people during the 1970s and 1980s, a time of dictatorship and economic turmoil here. There is a sense of a debt being repaid. “But it’s also true this is a new phenomenon for Peru, and for South America in general,” Scull told me. “These are countries used to sending migrants, not receiving them.”

Media sensationalism

Indeed, during the week i spent in Peru in late February, the strains were evident — and seemed focused in two main areas.

The first was a perceived competition for jobs, particularly low-salary ones. Approximately 70% of Peru’s workers work outside the formal economy — above the Latin American average. Peru has in many respects been the region’s most successful economy over the past decade, averaging better than 4% growth a year, while poverty has fallen sharply. But the high degree of informality means there is still a day-to-day scramble for jobs — and residents on the periphery of Lima whom I spoke with felt besieged. “There’s always a Venezuelan willing to do a job for half the pay,” said Juan Pardenos, a construction worker. Scull, the ambassador, estimated that 90% of Venezuelans working in Peru do so without a formal labor contract. Tensions rose further when the economy slowed in 2019, growing just 2.2%. The coronavirus crisis seemed certain to make the competition for work — and services such as health care — dramatically worse.

The other source of tension: the perception that Venezuelans are to blame for a crime wave. This is almost certainly false — Venezuelans account for 2% of reported crimes, and 3% of the population, meaning they commit fewer crimes on average than Peruvians do. But, just as in the immigration debate in the United States, this doesn’t really seem to matter. Certain tabloid publications “never miss an opportunity to sensationalize a crime committed by Venezuelans,” said Luisa Feline Freier, a professor focused on migration at Peru’s Universidad del Pacífico.

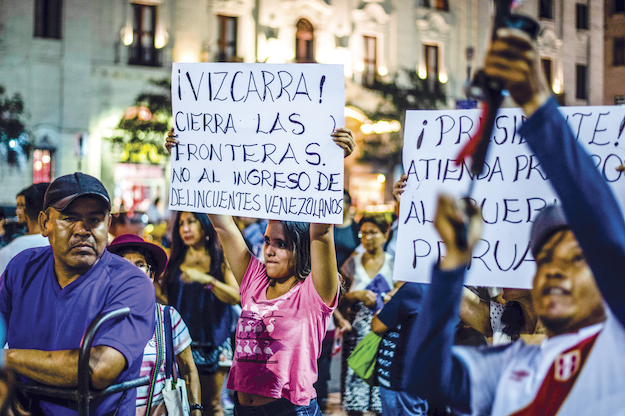

Curiously, the strongest anti-Venezuelan sentiment in polls is found in the interior, especially in the mountains, where the fewest Venezuelans actually live. Freier, who is German, noted a similar phenomenon in her country, where the far-right AFD party has thrived in eastern areas where refugees are scarce. But even in Lima, while I was there a few hundred participated in an anti-migrant march, carrying signs like “Peru is for Peruvians.”

President Martín Vizcarra’s government has tried to strike a balance — integrating Venezuelans into society, while also signaling to Peruvians that it understands the growing fatigue. Successive changes to visa requirements caused official net levels of migration to fall to zero by mid-2019. Meanwhile, programs like Lima Aprende, which added afternoon shifts to schools in the capital mainly to accommodate Venezuelan students arriving in the middle of the school year, aim to ensure they do not become part of a permanently marginalized group of society. “We know we have a window of opportunity to integrate people,” the foreign minister, Gustavo Meza-Cuadra, told me. “We know how important this is.”

A time for caution

So far, at least, there is no Peruvian equivalent of the AFD — and the handful of politicians who have attempted to incite anti-migrant sentiment have not been rewarded by voters. A candidate for Lima’s mayor who in 2018 accused Venezuelans of stealing jobs cratered in polls. I met Mario Bryce, a journalist who ran for Congress, who told me Venezuelans “have another way of living” and suggested “putting tanks” at the border to stop migration. He received barely 1,000 votes in January’s legislative election.

Still, after hearing so many Peruvians complain, from taxi drivers to street vendors and waiters, it was hard to escape the sensation that someone would eventually step into the void. And that was before the coronavirus arrived. David Smolansky, a Venezuelan emigre who oversees migration issues at the Organization of American States, said he was worried. “We’re seeing xenophobia rise all over the region,” he told me. “It’s a moment to be very, very careful.”