Latin America’s reliance on commodity exports has governments and investors trying to gauge the impact of the spike in prices in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The invasion has hindered trade and financial flows, disrupted supply chains and heightened financial volatility across the globe. Latin America’s direct trade and investment exposure to the countries involved in the conflict is limited, but its economies could still be significantly affected, depending on the scale and duration of the shock.

But not all countries in the region face the same risks. Who is best positioned to navigate the current chaos in commodities markets?

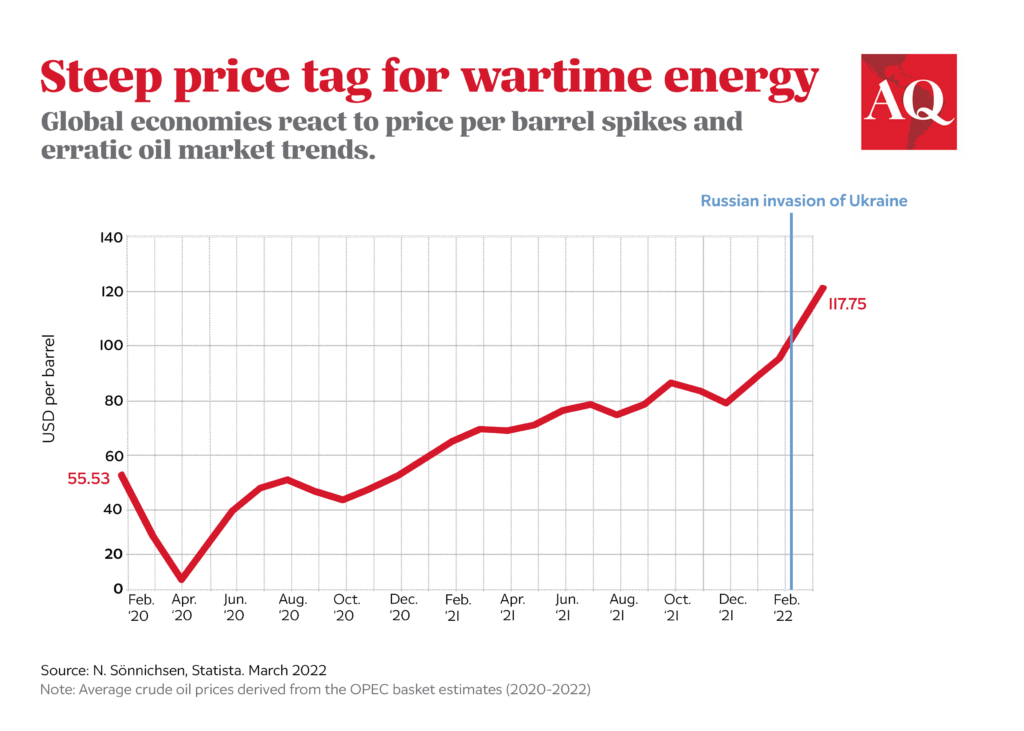

With trade disrupted, the conflict’s most immediate effect has been a surge in international food and energy prices from already high levels. The war could also affect global growth, hindering external demand for Latin American exports, particularly if Europe – the region likely to experience the most direct adverse effects – is widely affected.

The Ukraine conflict will likely result in larger current account deficits and mounting external financing needs across energy importer countries in Central America and the Caribbean. However, given Latin America’s reliance on commodity exports and waning trade dependence on Europe, the positive terms of trade shock may boost exports in many countries, providing a hard currency windfall that could help offset potential headwinds. On average, 72% of total exports in the largest Latin American countries last year were linked to commodities, compared to 62% in Africa, 51% in Middle East, 37% in emerging European economies and 25% in Asia. Moreover, although Europe was long a critical market for Latin American exports, its importance as an export destination has steadily declined as China’s has steadily grown. This is particularly true in Brazil, Chile and Peru, and should help protect exports from a slowdown in external demand.

Price impacts

The oil price surge should support the current account in Colombia and, to a lesser extent, Brazil. Colombia’s oil export volume has declined since 2015, but if oil prices average $100 per barrel this year, the windfall will amount to about 1% of GDP. Brazil’s current account, meanwhile, improves by almost 0.1% of GDP for every $10 rise in the oil price, since it regained net energy exporter status in 2017. Other regional energy exporters such as Ecuador and Venezuela would also benefit.

However, soaring oil prices would erode external accounts in Chile (which would be most affected among large economies), Mexico, Argentina and other net energy importers in Central America and the Caribbean, where El Salvador, Jamaica and Honduras could suffer the most.

Metal markets, meanwhile, will likely face relatively limited supply disruptions, which would especially benefit Peru and Chile, and a soybean price rally would provide a dollar windfall to Brazil and Argentina. Despite being less reliant on primary product exports than other Latin American countries, Brazil in particular should benefit from a generalized increase in global food and energy prices, given its more diversified commodity export base.

The impact on fiscal accounts should be generally neutral across major countries but negative for smaller economies in the region, given their need to increase subsidies and transfers to contain domestic energy prices. While higher oil-linked income should boost revenue in countries like Colombia and Ecuador, most economies will likely struggle to address widespread public finance weakness.

On the financial side, increased global risk aversion has not thus far resulted in major capital outflows from the region. This relative calm is due largely to improving prospects for commodity-exporting sectors as well as elevated interest rates due to firm monetary policy tightening in response to inflationary pressures. Attractive valuations stemming from local asset depreciation during the pandemic and the positive spillover from global investors trying to lower exposure to Eastern Europe also improve the panorama. However, Latin America could still experience sudden, significant capital outflows if the conflict escalates and effects on the world economy intensify, particularly in the context of monetary policy tightening in the U.S.

Inflation will be the region’s principal challenge as the shock will add to already broad-based pressure across consumer price categories, exacerbating tensions and tradeoffs. The heavy weight of imported food and energy in inflation indexes means that surging commodity prices will quickly translate into headline inflation pressure. This includes the potential for more sustained and widespread effects on domestic prices, adverse impacts on inflation expectations and further erosion of purchasing power, especially for those with lower incomes. Thus, the risk of an extended and forceful monetary policy tightening cycle that could weigh on economic growth is on the rise. Given fragile public finances, the hard-earned credibility of the inflation targeting regimes established in many countries over the last decades will prove vital to containing inflation, preserving financial stability and fostering conditions for steady growth.

Latin America is, so far, weathering the storm relatively well, but a prolonged war and another round of supply chain disruptions could quickly unravel its fragile stability.

–

Castellano is the head of Latin America research at the Institute of International Finance