This article was corrected on March 31.

Governments on both the right and left in Latin America have failed to condemn the invasion of Ukraine, reflecting Russia’s growing influence. Now, as leftists with anti-liberal leanings appear poised to dominate this year’s slate of elections, a new “Pink Tide” will only make it more difficult for the U.S. and the West to counter Russia’s inroads in the region.

Growing opposition to tenets of classical liberalism like open markets, multilateralism and democratic norms has played into Russia’s hands, but so has U.S. indifference. China has eclipsed the U.S. as the largest trading partner for most of the region, and Russian vaccine diplomacy has bested that of the U.S. Sputnik vaccines were the first to arrive in Argentina, Paraguay, Nicaragua, Bolivia and Ecuador, so it’s no surprise that these countries, with the exception of Paraguay and Ecuador, did not sign the OAS declaration condemning the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Latin American foreign policy traditionally appeals to defense of sovereignty and the peaceful resolution of disputes, but this discourse is often used to avoid taking definitive positions. No country from the region has yet imposed economic sanctions on Russia, and Russia’s military involvement in places like Syria—where its human rights violations are well documented—did not prevent Latin American presidents from deepening diplomatic and economic relations.

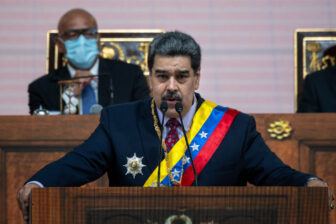

To counterbalance their sometimes difficult relationships with Washington and the West, leftist leaders like Argentina’s President Alberto Fernández, Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro and Bolivia’s former President Evo Morales bolstered their countries’ ties with Russia. Morales has been especially outspoken in Putin’s defense, blaming the United States for “confronting” Russia and Ukraine.

Others have sent mixed signals; the Peruvian and Mexican foreign ministries condemned the invasion, but President Pedro Castillo of Peru has shied away from speaking about the war, and President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has underscored Mexico’s neutrality. In Argentina, Fernández hasn’t gone beyond generically denouncing the use of violence. Chile’s newly elected Gabriel Boric has been the only leftist president to criticize Putin directly.

These varied responses reflect the two kinds of left coexisting in the region in the midst of a second “Pink Tide”: a progressive left and a traditional left. The former, typified by Boric, is more democratic, does not wish to do away with the liberal international order and has openly criticized the invasion. The latter, meanwhile, has a worldview grounded in a staunch rejection of U.S. imperialism, which plays into its reluctance to condemn Putin. As historian Pablo Stefanoni recently explained, the traditional left generally supports policies that push back against Western imperialism, regardless of the consequences.

This left is also skeptical of liberalism, which it considers a tool of Western imperialism, so its adherents are inclined to support authoritarian, anti-liberal figures like Putin. This is why some have blamed the Ukraine invasion on NATO aggression or echoed Russian claims of “denazification”. In fact, intensifying sanctions and international pressure on Russia might strengthen the view that opposition to its invasion is another imperialistic ploy from the West—or at least help traditional leftists frame it that way.

(Mikhail Klimentyev/Sputnik/AFP via Getty Images)

Latin America’s traditional left appears poised to dominate this year’s slate of elections, and its Cold War mentality will only exacerbate polarization as the political center continues to crumble in countries across the region. Leftist Gustavo Petro looks set to win Colombia’s upcoming presidential vote, and Lula da Silva’s likely victory in Brazil would probably strengthen that country’s relationship with Russia. Meanwhile, Peru’s government is as chaotic as ever in the wake of a highly polarizing election. To make matters worse, elements of the region’s right are shifting toward populism and authoritarianism, encouraged by international far-right parties like Spain’s Vox. These anti-liberal strains on the right have also tempered criticism of Putin, as evidenced by Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro’s refusal to condemn the invasion.

The U.S. will find it increasingly difficult to chip away at Russia’s influence in the region. However, there are openings; the traditional left can be pragmatic despite its ideological leanings. Maduro, for example, seems willing to explore the opportunities presented by the U.S. and European bans on Russian oil and gas; even as he publicly supports Putin, he’s participating in talks with the U.S. government on potential oil sales.

Even so, Russia will benefit from a backdrop of polarization and anti-liberalism. In the days just prior to the invasion of Ukraine, Putin met with both Fernández and Bolsonaro, and in early February Russia’s deputy prime minister visited Caracas, Havana and Managua. Russia will continue to pursue this kind of aggressive diplomacy—and Latin American governments will continue to be receptive.

This story has been updated to include Ecuador among the countries that received Russian vaccines first but did sign the OAS declaration condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.