As President-elect Donald Trump nears his inauguration, some fear his ascent to power will lead to the end of the USMCA North American trade agreement. Weeks ago, his threat of 25% tariffs on imports from Mexico and Canada triggered understandable anxiety. Bearish scenarios call for caution: starting a trade war against neighbors and dismantling the regional framework would have unintended yet predictable consequences, not least for the United States.

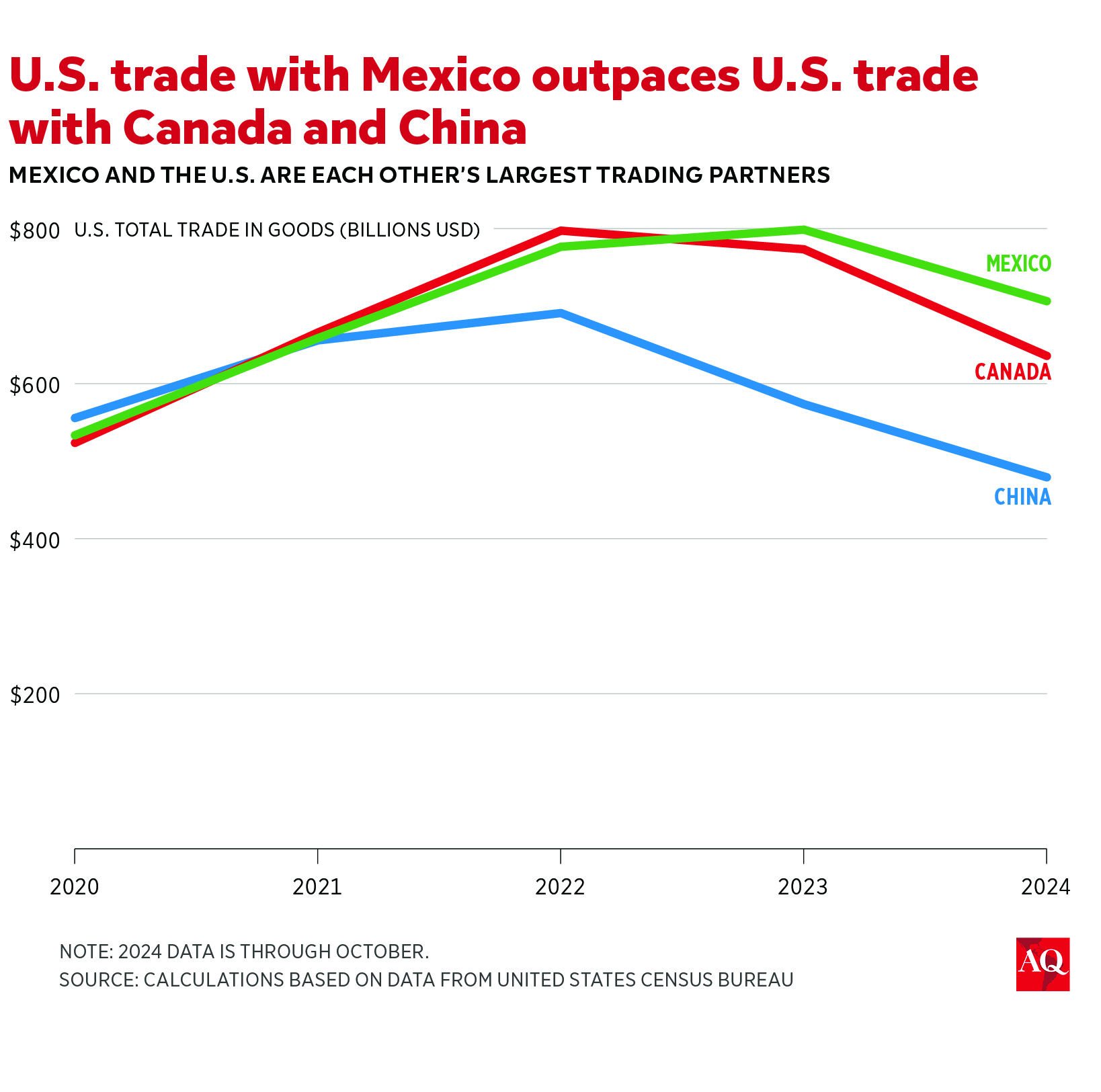

Today, USMCA facilitates record-breaking regional trade. The value of goods and services traded across North America nears $1.8 million every minute and is projected to exceed $2 trillion this year. For the first time since 2002, Mexico and Canada have overtaken China as the U.S.’s top trading partners, with regional commerce supporting approximately 17 million jobs across North America. Despite this positive trajectory, USMCA faces risks, with Trump returning to the White House and the agreement approaching a critical juncture: its 2026 review.

With the global landscape changing, it’s clear that USMCA’s future will be shaped not only by the Trump administration’s priorities but also by the three countries’ ability to navigate emerging geopolitical and economic challenges. U.S. policy has grown increasingly protectionist, viewing trade and investment with its main partners as a zero-sum game and tariffs as catch-all solutions. In the name of enhancing national security and boosting domestic manufacturing, a shift towards economic isolationism would impose higher costs on U.S. producers and consumers.

Meanwhile, geopolitical tensions, particularly with China, have intensified and show no signs of abating. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the ongoing instability in the Middle East have added uncertainty to global supply chains at a time when generative AI is ushering in transformational changes in the production and distribution of goods and services. North America must respond to these challenges with a forward-looking strategy in the 2026 review that ensures USMCA’s resilience and relevance under shifting global sands.

The question is simple: Why disrupt something that’s working well for the three countries?

Trade and integration at a crossroads

The USMCA represents a paradigm shift in trade agreements in two critical ways. First, it reflects evolving trade priorities, moving beyond cost reduction and efficiency to more managed trade and a central emphasis on workers’ rights, earning bipartisan support in the U.S. Congress.

At the same time, it provides a review mechanism: following each country’s internal consultations, Mexico, the U.S., and Canada will begin the review with two basic scenarios. First, all three countries agree to extend USMCA for another 16 years through 2042, strengthening stability. Alternatively, at least one country opts not to extend, triggering annual reviews for the subsequent 10 years. If no consensus is reached within this period, USMCA will expire on July 1, 2036.

An unsuccessful review would inject uncertainty into North American trade and investment relations, potentially disrupting economic growth and integration gains made over the last 30 years. However, it would not completely halt trade and investment. USMCA rules would remain in effect, Mexico and Canada could still benefit from preferential access to each other’s markets through the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), and the three countries could use World Trade Organization (WTO) rules, although under its weakened dispute settlement capabilities.

This outcome would nonetheless impose unnecessary costs on trade and investments vital for North America’s long-term security, competitiveness, and other goals, including labor and environmental standards.

U.S. withdrawal from North America?

In Trump’s second administration, withdrawal is a third and unlikely scenario. Article 36.6 of the USMCA allows any country to unilaterally exit the USMCA with six months’ notice, regardless of the review process. While no government has signaled an intention to invoke this provision, there could be a temptation to use it as a bargaining chip, reminiscent of Trump’s approach during his last term that led to NAFTA’s renegotiation. Even if a calculated bluff, the current threat of tariffs sends a chilling message to investors in the U.S. and abroad.

Mexico and Canada are now the U.S.’s first and second trade partners. The three countries produce many manufactured goods together, above all automobiles and auto parts, which would increase in price in North America and lose market share in third countries. Also, both countries are crucial markets for U.S. agricultural exports and would be difficult to replace. Taxing auto parts or agricultural products—with anticipated retaliation from Canada and Mexico—would have compounding effects on the U.S. economy.

If the U.S. imposes across-the-board tariffs against its main trade partners, the country would suffer significant job losses, and the optimism on nearshoring—which has been years in the making—will be hurt. It’s well known that since his 2000 book The America We Deserve, Trump has always aspired to be his own trade representative. He famously declared in the book: “What I would do if elected president would be to appoint myself U.S. trade representative.” He’s trying to do that again to start his second term, but the stakes are now higher than ever, not only for Mexico and Canada but also for the U.S.

Uncertainty regarding the precise degree to which Trump will be involved in trade policy formulation is compounded with uncertainty on a potentially expanded role for the Commerce Department on trade policy. USTR has traditionally led trade policy as part of the Executive Office of the President. Recently, the center of gravity on trade policy has veered toward the Commerce Department and the president, and this trend will likely be reinforced regardless of who ends up running Commerce and USTR after Senate confirmation. If short-term political expediency prevails over careful cost-benefit assessment and input from experienced staff, costly mistakes could be made even if they are subsequently corrected.

USMCA and global competitiveness

The three countries must prioritize the long-term strategic benefits of trade and economic integration over short-term political wins compounded with economic costs. North America needs elected officials and business leaders who champion pragmatic solutions and innovations that strengthen its competitive edge and ensure the agreement’s continuity and evolution. Failure to extend USMCA would benefit global rivals like China and Russia, who stand to gain from a divided, less competitive, and less resilient North America.

While the Trump administration may be tempted to link non-trade issues, such as migration, drug trafficking, and security, with USMCA’s review, these challenges are better addressed independently. Canada and Mexico will likely insist on separate tracks and be willing to make significant progress while keeping trade discussions separate. Handling critical issues separately would allow for a constructive approach to managing two of the U.S.’s most complex bilateral relationships without jeopardizing the economic certainty necessary for job creation.

Instead of wielding threats that may yield some immediate concessions but risk alienating key allies, a more productive approach would involve using the 2026 review to ensure job creation through USMCA’s continuity. Addressing shared challenges—such as countering China’s unfair trade practices, eliminating forced labor from supply chains, expanding digital trade, and making sure regulatory cooperation facilitates the development and adoption of generative AI—would reinforce the agreement’s relevance. Disagreements, while inevitable, must be resolved within a framework that prioritizes the shared benefits and enduring strengths of North American trade integration. Will the three countries be up for the challenge?