This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Guatemala.

During the first 50 years of U.S. control over Puerto Rico, the island’s governor was appointed by the White House. But in 1948, the first democratic election elevated Luis Muñoz Marín, a charismatic former pro-independence senator, to the post.

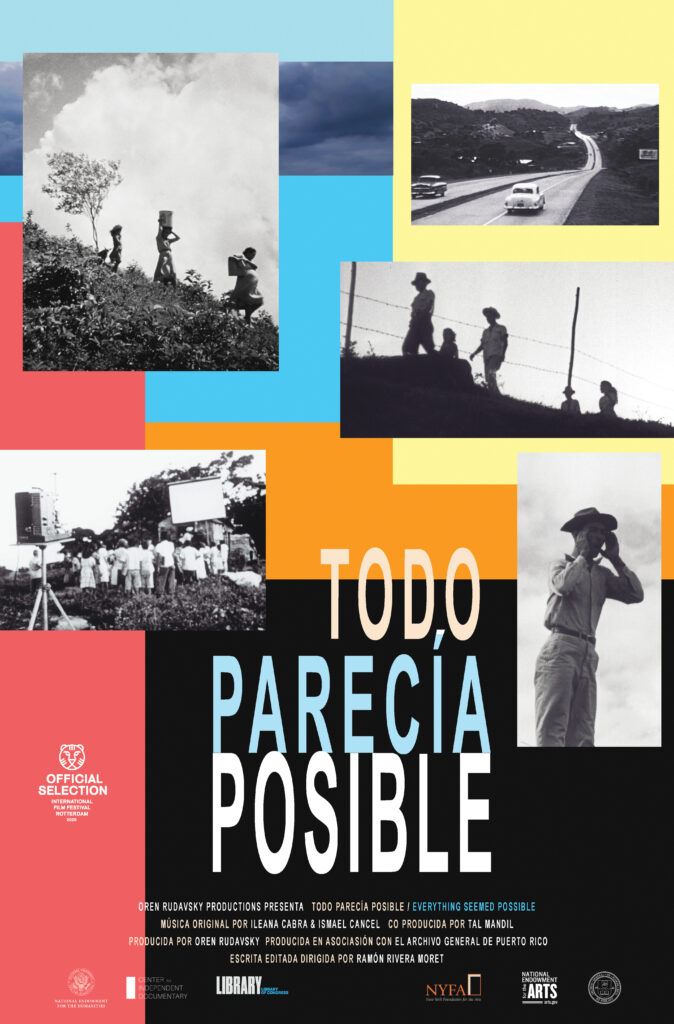

During his first year in office, Muñoz Marín embarked on an ambitious attempt to transform Puerto Rico into a commonwealth with its own constitution and from an agrarian society into an industrial one. At the same time, he established the Division of Community Education, a government agency that produced more than 100 films about life on the island for public consumption. This rare cinematic archive is the animating force behind Ramón Rivera Moret’s Everything Seemed Possible, a moving new documentary about Puerto Rico in the 1950s and 1960s, a period when progress—economic and otherwise—appeared all but inevitable.

Everything Seemed Possible (Todo parecía posible)

Written and Directed by Ramón Rivera Moret

Conceived by Ramón Rivera Moret and Oren Rudavsky

Screenplay by Ramón Rivera Moret

Produced by Oren Rudavsky

Co-produced by Tal Mandil

Distributed by Oren Rudavsky Productions and First Run Features

Puerto Rico and United States

Voiceover narration by Rivera Moret, a professor at the Rhode Island School of Design, intersperses personal anecdotes with an account of the island’s modern history, as scenes from the Division’s movies occupy the screen. When the agency began making films, most Puerto Ricans lived in small, rural communities. Agency staff would travel to the countryside and speak with locals about the problems they faced. “This was reported to the offices in San Juan,” Rivera Moret explains, “where the members of the Division discussed what stories to tell.” Actors were generally recruited from the villages where the scripts originated.

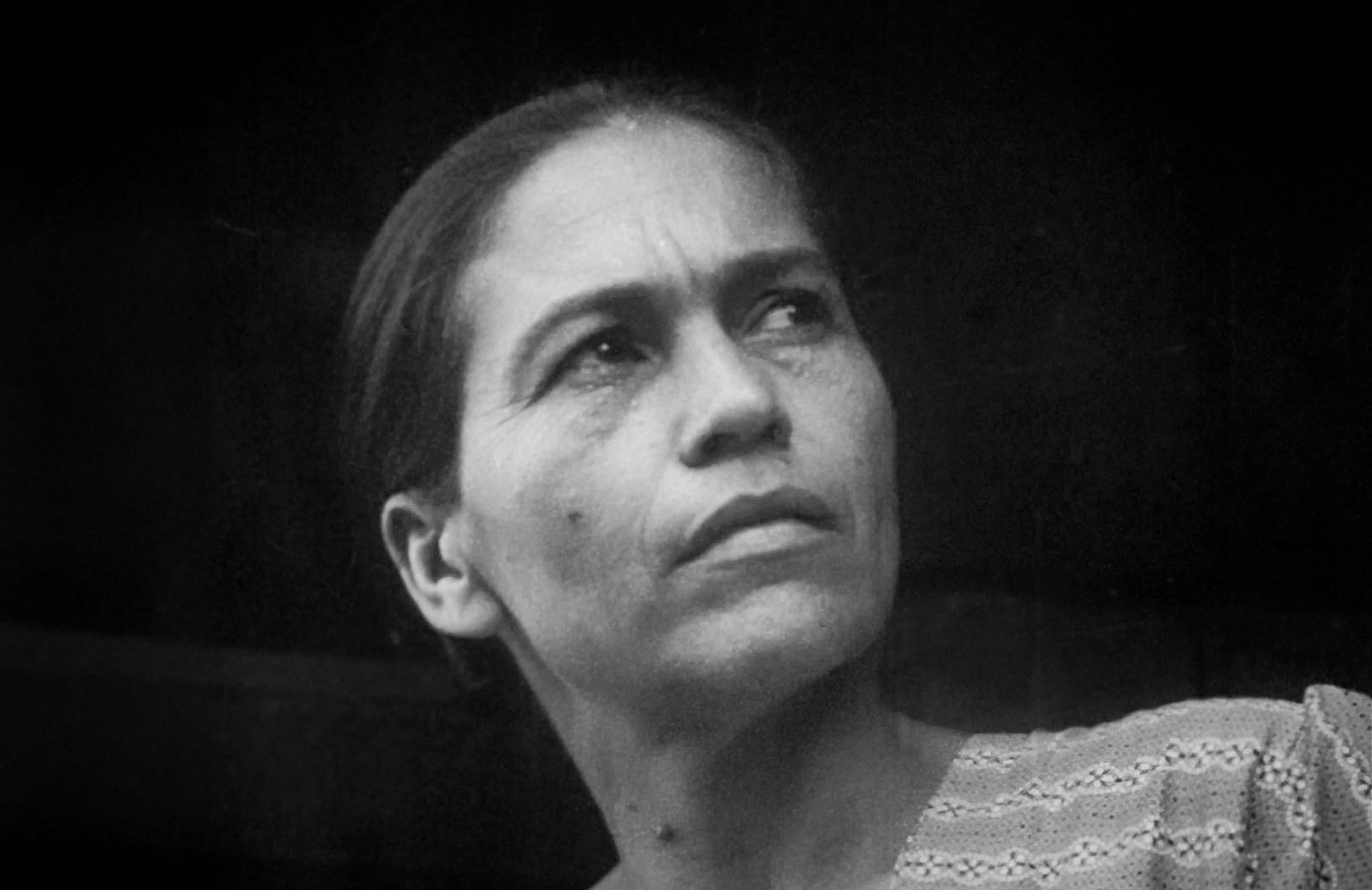

The films, visually stunning in their own right, tackle a startling range of issues with seriousness and honesty. In Modesta (1956), a young, pregnant mother grows tired of her husband’s impossible domestic demands, converting a group of female friends into the League of Liberated Women. “We must become guardians to defend our rights,” Modesta urges her peers.

In El gallo pelón (1961), would-be businessman Esteban finds success selling washing machines to his neighbors, only to incur their frustration: His village has no electricity, so the machines are useless. They are instead put to use as tables.

Rivera Moret has a personal connection to these films: His great-uncle worked as a director of photography in the Division. Yet broader concerns come through in Everything Seemed Possible—for example, in a rare clip of a speech by Muñoz Marín, where he asks his fellow Puerto Ricans, “Are we to give more importance to material things or to questions of the soul?”

Today, the island faces a similar choice. Puerto Rico is still reeling from the painful aftermath of 2017’s Hurricane Maria, when hundreds of thousands lost homes and the island’s electrical grid all but collapsed. In the last three years alone, residents—around 40% of whom live in poverty—have experienced more than 230 power outages.

Problems like these seem to cry out for concerted economic change, but Puerto Ricans also know that vast transformations often come at a steep if intangible cost. In the latest hit album by Puerto Rican reggaeton star Bad Bunny, DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS, many songs lament the island’s regrettable material conditions (“She looks pretty even though sometimes things go badly for her”) even while they fear the prospect of U.S.-style development (“I don’t want them to do to you what they did to Hawaii”). Most significantly, the reggaeton tracks blend with traditional folk genres from the island, like plena and bomba, that younger generations—and certainly international listeners—have mostly overlooked.

By conjuring and revaluing Puerto Rico’s rich cultural past, Rivera Moret and Bad Bunny alike make the case for their island’s self-worth. They also attempt to recapture a sense of hope, one rooted in remembering, not forgetting.