This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on millennials in politics

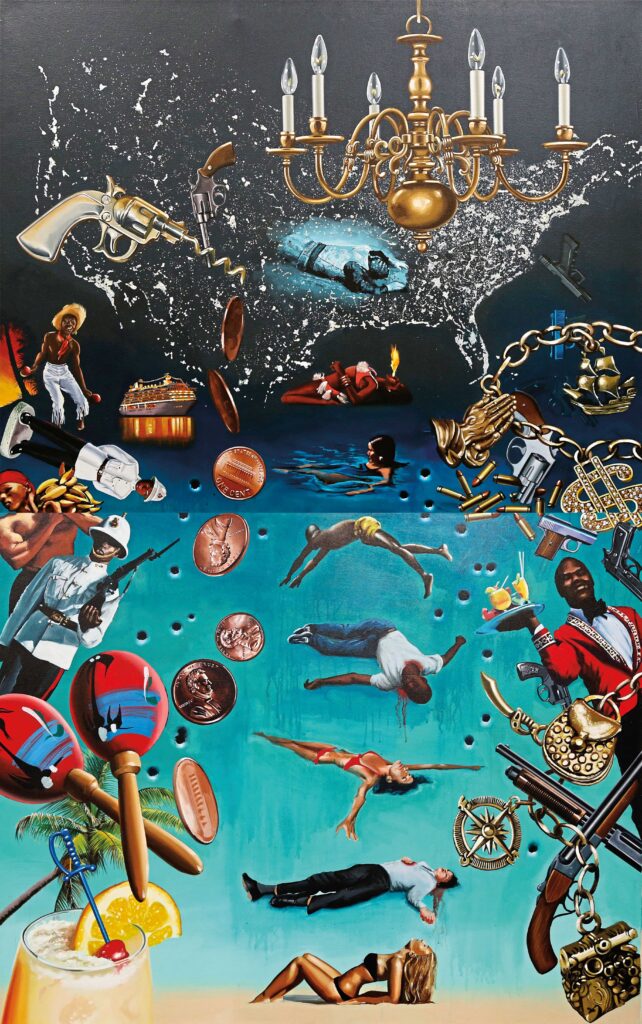

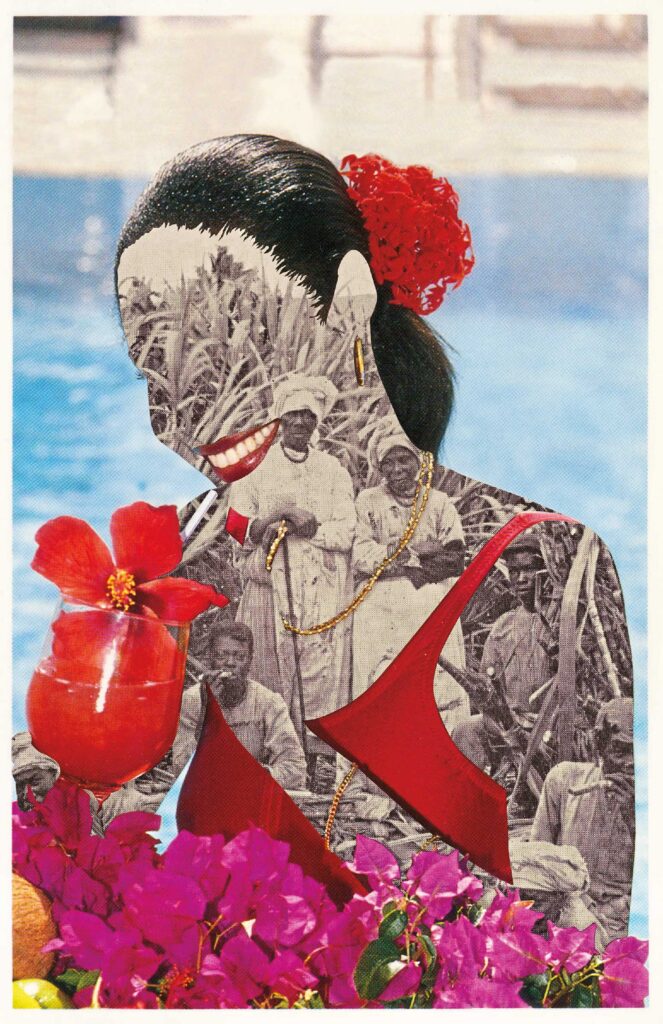

In all their diversity, it is the colonial legacy of the occupation of European empires and the contemporary yoke of transnational capital that bind the islands of the Caribbean together. For an observant resident or visitor to the Caribbean, the link between the plantation and tourist economies is evident, whether measured by the economic impact of the industries, the resignification of spaces from one era to the next or the importance each has played in the creation of stereotypes for the region.

Within this context, the exhibition Tropical Is Political: Caribbean Art Under the Visitor Economy Regime at Americas Society investigates ideas of paradise, including “fiscal paradise” (the literal translation of “tax haven” in many languages) as portrayed in Caribbean art. More specifically, it examines the region as subject to an economic regime that transforms its societies into ones organized to serve the visitor—a social paradigm at the intersection of finance and tourism.

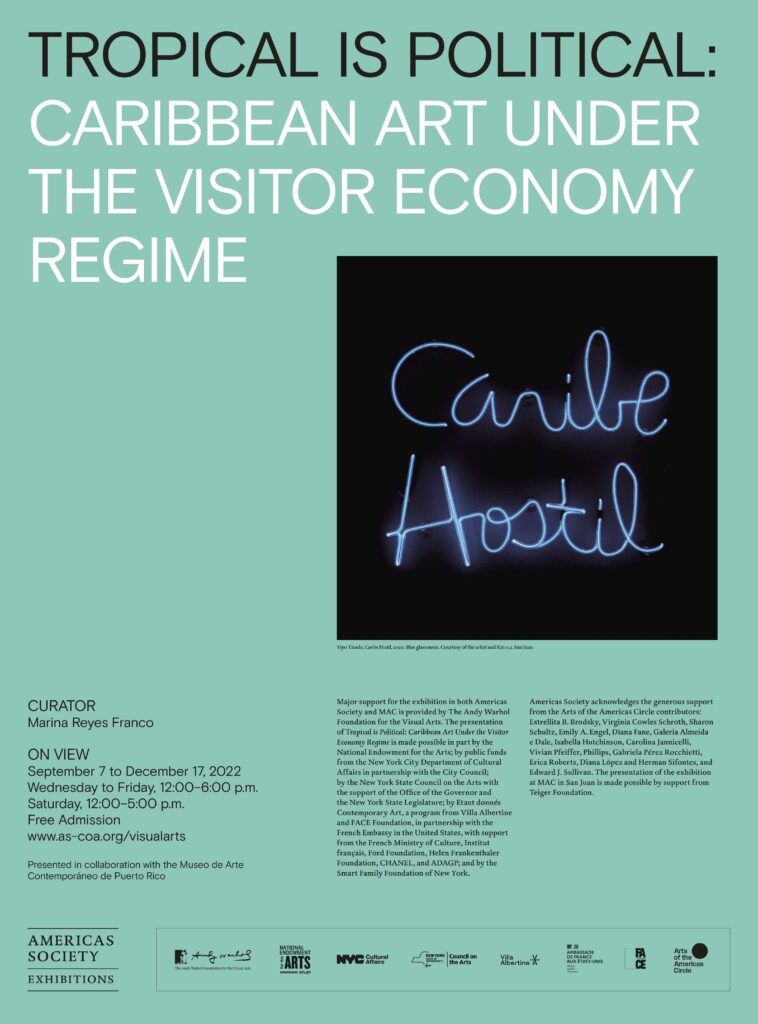

Tropical Is Political: Caribbean

Art Under the Visitor Economy Regime

Curated by Marina Reyes Franco

September 7–December 17, 2022

Americas Society

Many Caribbean countries have transitioned from agriculture-based to tourism-supported economies. Economies once sustained by the cultivation of monoculture crops on plantations for export to metropole nations in North America and Europe now rely on income from visitors from the wealthiest countries, attracted by pristine beaches and banking secrecy.

This transition is a legacy of colonialism and empire, which have left an undeniable mark on Caribbean culture by shaping the way we relate to ourselves, to each other and to nature itself. Even after many Caribbean nations became independent in the mid-20th century, political decolonization did not free these new countries from the exploitative ideas which global tourism relies on to thrive. The plantation-to-tourism pipeline is alive and well in some parts of the Caribbean, where former plantation lands have become golf courses and resorts that exclude the descendants of the people who were exploited in them from the coasts, making the link between the settler-colonial legacy and present-day exploitation abundantly apparent.

Although the tourism industry in the Caribbean started in the 19th century, it experienced a boom in the 1950s and 1960s, when the region began to transform towards a service economy rooted in hospitality, an industry standard that stabilized and solidified in the 1990s. Simultaneously, the rise of the financial services sector emerged in many Caribbean countries, becoming the second most important industry in the region. These decades also roughly encompass the period when most of the participating artists in this exhibition (and myself) came of age in the Antilles. Tourism campaigns and a sense of performativity in our mere existence in relation to tourism has shaped us deeply, even in countries where tourism is not the main economic motor.

The artists included in this exhibition use diverse strategies and media to highlight the conditions of life and art in a region besieged by the commercialization of its people and land under the visitor economy regime. Works by Dionne Benjamin-Smith, Gwladys Gambie, Dalton Gata and others address critiques of self-representation and Caribbean sexuality, while Ricardo Cabret, Carolina Caycedo, and Donna Conlon and Jonathan Harker look at currency manipulation, bond debt and economic systems from the plantation to the more recent crypto investors. Airbnb, displacement and the struggle to retain access to our natural resources motivate Sofía Gallisá Muriente, nibia pastrana santiago and Viveca Vázquez. Through their works, but also through the way they develop their lives and careers, the artists featured in this exhibition propose ways of seeing and reinterpreting life in the Caribbean; not merely pointing out flaws but also the opportunities to transform ourselves and our future. A further emancipation from these legacies is necessary, and that is where the realms of culture and art can play an important role in expanding our imagination.

—

Reyes Franco is curator of the Tropical Is Political exhibition at Americas Society as well as of Puerto Rico’s Museo de Arte Contemporáneo