Fewer than three months into President Donald Trump’s second term, his administration’s focus on countering cartel activity in Mexico could not be more evident. On his first day in office, President Trump announced this policy priority by issuing an executive order designating certain cartels as Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs), and Attorney General (AG) Pam Bondi followed suit with a memo to all U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) prosecutors entitled “Total Elimination of Cartels and Transnational Criminal Organizations.”

The administration’s gameplan is playing out as expected, with the recent extradition of two alleged Barrio Azteca gang leaders to the U.S. to be prosecuted, and DOJ’s indictment of 14 alleged members of a prolific alien smuggling organization. What could this mean for Mexico? To understand the security and business implications, it is helpful to consider the legal underpinning of an FTO designation.

The designation places Mexico-based cartels like Cártel de Sinaloa, Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG), and Cárteles Unidos in the same category as Al Qaeda and ISIS. Their members are now considered enemy combatants. In theory, this paves the way for U.S. military action against them in Mexico. Trump’s nominee for ambassador to Mexico, Ronald Johnson, hails from the U.S. military and intelligence communities, shares Trump’s hawkish “America First” worldview, and has spent years in Latin America working on counterinsurgency matters. His recent stint as U.S. ambassador to El Salvador led to a close working relationship with President Nayib Bukele, known for his controversial strongarm tactics to address gang and cartel activity.

U.S. policy in Mexico is expected to promote hardline strategies, and Trump is already putting pressure on Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum to step up Mexico’s cartel-focused military interventions and stop flows of fentanyl and migrants, threatening tariffs if the country doesn’t show progress. In response, Sheinbaum has sent 10,000 troops to the border and made arrests and drug seizures. Rather than a full-on U.S. military action in Mexico, what is more likely is an aggressive expansion of U.S. use of intelligence-gathering drones in the country and surgical special operations.

Perhaps the greater effect of cartel FTO designation on Mexico, and something that has received less attention, is how the designation puts companies, both U.S. and Mexican, directly in the legal crosshairs for providing support to designated entities. Under the U.S. Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA), the U.S. government can criminally prosecute companies for providing “material support” to FTOs. The term is defined broadly to include any property (tangible or intangible) or services, including currency, financial services, lodging, personnel, and transportation. The DOJ has prosecuted companies for similar support of terrorist organizations in the Middle East – the French building materials manufacturer Lafarge S.A. paid $778 million in penalties in 2022 for security and other payments to multiple FTOs in Syria, including ISIS. The famous 2007 Chiquita Brands case involved protection payments to Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC)–that company paid a $25 million fine.

The view from Mexico

Having visited Mexico four times since Trump took office and discussed the legal implications of cartel FTO designation on the ground, it is clear there is a high level of incredulity among Mexicans. The notion of preventing all support to cartels seems far-fetched. Cartels in Mexico are no longer groups detached from society – they have morphed into highly sophisticated commercial enterprises with tentacles that stretch throughout the Mexican economy. They are heavily involved in sectors as vast as tourism, diesel fuel, real estate, poultry, and tortillas.

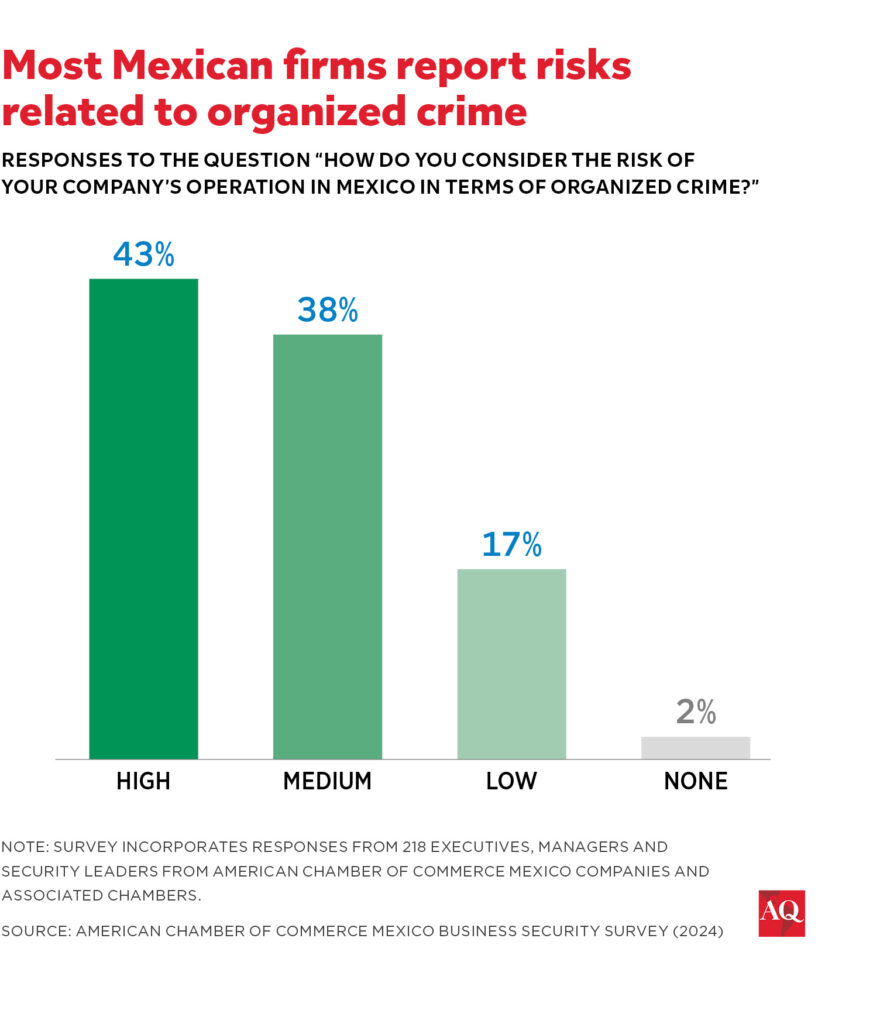

Cartels control highways, back mayors of certain municipalities, and insert themselves into companies’ procurement functions. A 2024 survey conducted by the American Chamber of Commerce in Mexico found that 12% of respondents said that organized crime has taken partial control of the sales, distribution and/or pricing of their goods. Forty five percent stated that they had received extortion demands for protection payments.

To extract protection payments (derecho de piso), some cartels have set up front establishments that simulate services to companies, issue invoices, and collect payments in a seemingly legitimate way. Relationships between companies and cartels can be symbiotic. A cartel might borrow a food service company’s truck, carefully unload the goods, use the truck to move illicit goods or people down central thoroughfares, reload the goods, and return the truck, all with cooperation from local police. The company is then permitted to move on with its business without cartel interference.

Under U.S. law, this type of support can now be criminal. The U.S. government can now pursue Mexican companies that make payments or provide other support to cartels, even if those transactions have no U.S. nexus.

Another legal tool unlocked by the FTO designation is civil forfeiture whereby the U.S. government can seize assets, including those of a Mexican entity, that have an arguable connection to an FTO. Imagine a scenario whereby a Mexican shipping company is carrying avocados to China and the U.S. government has reason to believe that the cargo is linked to an FTO–given the prominence of cartels in the avocado industry. The U.S. government can direct the vessel to a U.S. port and seize title to the goods. U.S. courts are now considering whether a specific U.S. nexus is required for such seizures and whether the U.S. government must demonstrate specific intent as to the non-U.S. company.

What’s next

Will the Trump administration really utilize such powers to proceed against Mexican companies that support cartels? A factor increasing the risk is that AG Bondi has now decentralized DOJ enforcement. She has directed that U.S. Attorneys’ offices throughout the country “lead the charge” against cartels and suspended requirements of authorization by the DOJ’s Criminal Division for an investigation or prosecution associated with cartels. This could give rise to a fragmented approach to enforcement with minimal coordination from senior levels of the Trump administration. Cases could also move more quickly.

It is true that obstacles exist to proceeding against Mexican companies in the U.S. for supporting FTOs. The U.S. government would need to overcome the practical challenge of getting a non-U.S. defendant before a U.S. court.

Even if the DOJ does not ultimately bring ATA cases against Mexican companies, the ATA and other statutes enable harmed plaintiffs to bring cases. Under the ATA’s civil liability provisions, a U.S. national injured because of an act of international terrorism may sue a company to recover threefold the damages the person sustained if the company engaged in an act of international terrorism by providing material support to the responsible FTO or knowingly provided substantial assistance to the perpetrators of an attack committed, planned, or authorized by an FTO. There is an active plaintiffs’ bar that looks to develop cases against companies allegedly providing material support to FTOs. For example, after a long-running civil wrongful death case against Chiquita, a jury in 2024 awarded $38.3 million in damages to the families of eight men killed by the AUC.

Mexican companies and multinational firms operating in Mexico should start getting up to speed on these dynamics. There is much they can do right now to mitigate FTO risks. They can map potential cartel exposure, ensure strong controls around areas where payments are likely to occur, perform risk-based due diligence of third parties and employees for cartel affiliation, and train personnel on the need to escalate issues when they arise. The Trump administration is treating this as a Day One issue, and companies should too.