I recently tried a virtual reality experience by Venezuelan activists that recreated a cell in the Helicoide, the notorious detention center in Caracas operated by local intelligence services. You walk into a tiny, dark cell, listen to flies, and hear narrations of the abuses people suffered in there, in their own voices. It was a harsh reminder of the many accounts I’ve gathered over the years from victims of Venezuelan security agents’ arbitrary arrests and torture.

Sadly, their experiences are far from virtual – and make no mistake, they continue today.

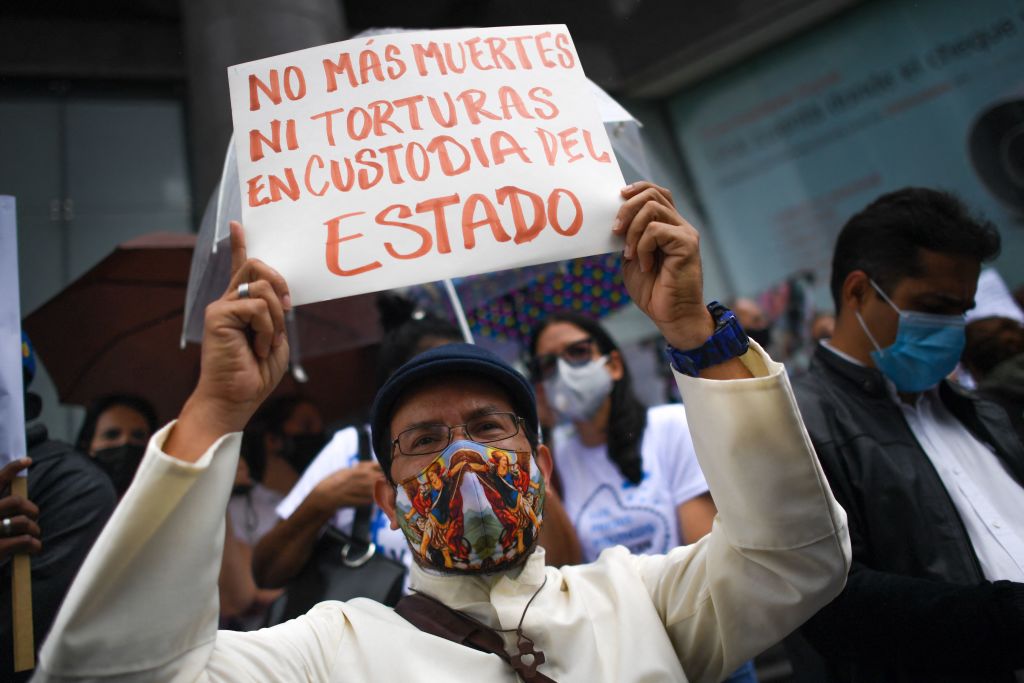

Several politicians around Latin America, especially some on the ideological left, have recently contended that the human rights situation in Venezuela is improving. But in reality, the Nicolás Maduro government’s crackdown on dissent continues, without justice for victims. Now is not the time for the international community to reduce scrutiny of the Maduro government. In fact, several upcoming events including a meeting of the United Nations Human Rights Council make outside pressure as important as ever.

The Venezuelan organization Foro Penal counts 245 political prisoners today, many in detention centers such as the Helicoide. Detainees have experienced horrendous torture, including electric shocks, waterboarding, and sexual violence.

In a recent report, U.N. Human Rights High Commissioner Michelle Bachelet described killings by law enforcement during security operations. At Human Rights Watch, we found that government data itself reveals that security forces killed at least 19,000 people between 2016 and 2019. Many were recorded as resulting from “resistance to authority,” but we found that many were extrajudicial killings. Bachelet’s team, which has a presence in Venezuela, recently lost access to the Helicoide.

Meanwhile, Venezuelan authorities continue to harass and prosecute independent journalists, human rights defenders, and civil society organizations that are working to address the human rights and humanitarian emergencies. In one example, after Javier Tarazona, a human rights defender from the nongovernmental organization Fundaredes, exposed links between Venezuelan security forces and armed groups, the authorities arbitrarily detained him in July 2021. He remains in prison.

Venezuelan authorities have repeatedly failed to protect Indigenous populations from violence, forced labor, and sexual exploitation in the context of large-scale illegal mining operations. Human Rights Watch has documented horrific abuses—amputations, shootings, and killings—by groups controlling illegal gold mines in southern Venezuela. In the Orinoco and Amazon jungles, such mining has led to deforestation and polluted waters. Several Indigenous people have been killed in recent months, human rights organizations report, including Virgilio Trujillo, an Indigenous leader who opposed illegal mining.

Impunity is the norm, despite compelling evidence of widespread abuses. Recent changes to Venezuela’s justice system may be further weakening it. The process to select new justices for the Supreme Court—which plays a critical role in the appointment and removal of lower court judges—was not independent, and justices who had failed to act as a check on executive power were reelected.

International scrutiny

Given the lack of judicial independence, international accountability remains as important as ever. A major development was the decision by the International Criminal Court (ICC) Prosecutor Karim Khan last November to open an investigation into alleged crimes against humanity in Venezuela. For the first time, victims could see progress toward their abusers being held accountable for their crimes. Not surprisingly, Venezuelan authorities asked him to defer his investigation, claiming “genuine will” to investigate abuses themselves. But the prosecutor wants to reject the request and move forward with his probe.

The prosecutor’s decision followed strong reporting by the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Venezuela (FFM), appointed by the United Nations Human Rights Council in September 2019. In two damning reports, they concluded that there were sufficient grounds to believe crimes against humanity had been committed and that the justice system had served as a mechanism of repression, instead of a guarantor of rights. The mission implicated high-level authorities, including Nicolás Maduro himself.

The mission’s experts will present their third report at the 51st session of the Human Rights Council, which starts September 12. This will be their final report, unless the council extends the mandate with a majority vote.

Venezuelan authorities have undertaken a strategy of apparent, but not genuine, engagement with the Human Rights Council’s procedures, as they did during the previous mandate’s renewal, attempting to show that the mission is unnecessary. They should not get away with it.

Venezuelan and international human rights groups are advocating for the extension. For its creation and first renewal, a group of Latin American countries, including Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Paraguay, and Peru, together with Canada, took the lead.

They should repeat their leadership because Venezuelan authorities will only give ground if international scrutiny persists. Renewing the mission’s mandate will allow experts to continue crucial work, complementing the work of the ICC and other international mechanisms.

U.N. High Commissioner Bachelet has a team monitoring and reporting on human rights violations and providing technical assistance to Venezuelan authorities but does not collect or preserve evidence for accountability processes, as the mission does.

Evidence gathered by the mission could also help the ICC, which can establish individual criminal responsibility for egregious crimes, but usually only in a small number of cases due to resource constraints. But the mission’s lens is also broader than the ICC’s, focusing on structural problems. And while the ICC investigation could take years, the mission reports annually on rights violations.

Venezuelan presidential elections are scheduled for 2024, legislative and regional elections for 2025, and if the past is any indicator, repression could increase as the campaign season progresses. The mission can play an essential, early-warning role and prevent further restrictions on civic space, freedom of speech or association, and crackdowns on dissent.

The resistance of some Latin American governments to leading efforts for the mission’s renewal seems based on a false premise that doing so would undermine attempts to engage with Venezuelan authorities. Yet, historically, those authorities have failed to make concessions voluntarily to protect the rights of Venezuelans. There is no reason to think that will change. No negotiated solution to transition back to democracy is possible without incentives—and international pressure and accountability are essential to create them.

Latin American leaders who are committed to restoring democracy and human rights in Venezuela, regardless of where they place themselves on the ideological spectrum, should unite in support of a resolution to renew the mission’s mandate. They should lead by example and then urge all Human Rights Council member states to support it.

—

Taraciuk Broner is deputy Americas director at Human Rights Watch