ASUNCIÓN — Every winter, Paraguayans gather to burn effigies, known as Judas Kái, of people they dislike. This year, among the usual roll call of corrupt senators and scandal-ridden local officials, a new mannequin featured widely: President Santiago Peña.

A telegenic 45-year-old economist who worked for the IMF and served as Paraguay’s finance minister, Peña won the April 2023 election over a divided opposition. Heading up the conservative Colorado Party, which has run Paraguay for all but five of the last 77 years, Peña promised more police on the streets, 500,000 new jobs, cheaper gas, and to keep filling government posts with loyal Colorados. With his slogan Vamos a estar mejor (“Things will get better”) winning over a weary public, his party scored a majority in both houses of Congress, with a trickle of defections since swelling the ruling bloc even further.

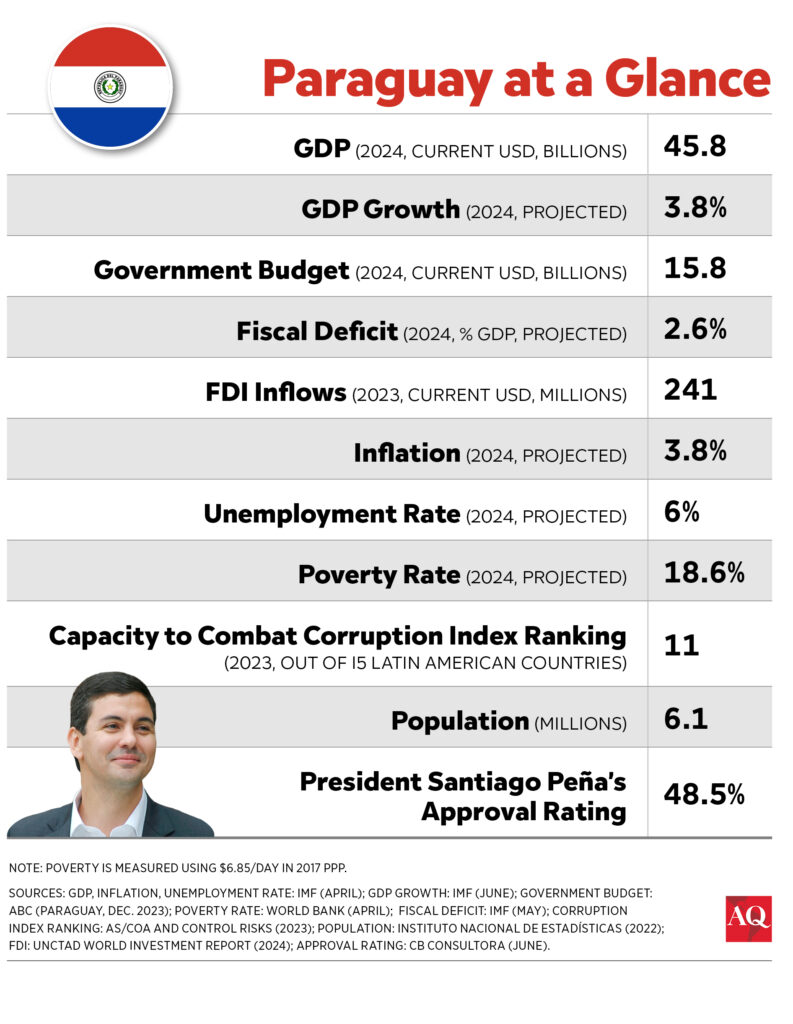

As Peña marks one year in office on August 15, polls suggest Paraguayans are split on his presidency, with 48.5% of those surveyed in June rating him favorably, compared to 48.3% against. Supporters praise his handling of the economy—Paraguay’s GDP is expected to grow almost 4% this year, one of the highest growth rates in Latin America—and actions to tackle organized crime. But critics argue that Peña has failed to outline a strategy to address corruption or a threadbare social safety net, while rule of law and democratic guarantees have also come under renewed pressure.

They also argue that Horacio Cartes—one of the country’s richest men, the leader of the Colorado Party, and Paraguay’s president from 2013-18—still looms too large in the country’s politics. The U.S. sanctioned Cartes last year, accusing him of bribing legislators and other acts of corruption, as well as doing business with Hezbollah, all of which Cartes denies. Last week, the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) followed up with sanctions against Tabacalera del Este S.A. (Tabesa), a cigarette-maker company, for paying millions of dollars to Cartes, its former owner.

“This government clearly has two heads: the president of the republic and the president of the party,” said Dionisio Borda, a former finance minister under both Colorado and center-left administrations. Cartes, he argued, “is the de facto president of Paraguay” and is attempting to consolidate “an authoritarian project going back ten years.”

Measured gains

Peña has downplayed such talk. “Horacio Cartes is a hugely important person in Paraguay and in the political movement in which we’re active,” Peña said in a radio interview, “but that doesn’t mean that I’m not my own person.” The most recent edition of the Economist Intelligence Unit’s closely followed Democracy Index upgraded Paraguay from a “hybrid regime” to a “flawed democracy.”

On the economic front, the president can take some credit for Moody’s recent decision to improve Paraguay’s sovereign credit rating to investment grade, citing institutional reforms, stable fiscal policy, and public investments in infrastructure under successive administrations. Peña has appointed experienced and relatively independent figures to the Finance and Economy Ministry and the Central Bank.

Moody’s also praised Peña’s merger of the tax and customs agencies, which helped raise tax revenue by 24% year-on-year in the first half of 2024. Yet the debt-to-GDP ratio still climbed to 38% of GDP in April, up from 23% in 2019, in large part because taxes—levied at just 10% on personal and corporate income—recoup barely 15% of GDP, the lowest share in South America. Meanwhile, Paraguay’s inequality remains stubbornly high, and Moody’s warned that inadequate schools and essential services could hold Paraguay back.

“The greatest challenge facing the government is mobilizing resources to meet social demands like health and education,” Borda told AQ. This is easier said than done. In June, for example, an opposition bill to raise tobacco duties by 2% from 22%—among the lowest in the world—to fund Paraguay’s ailing National Cancer Hospital was shot down by legislators loyal to Cartes, whose fortune rests on cigarette manufacturing.

On drug cartels, Peña has taken swift action. In December, security forces stormed Tacumbú, a notoriously lawless prison in the capital, seizing drugs and guns and leaving 11 prisoners and one police officer dead. Inmates were stripped and filmed at gunpoint in the style of El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele—an acknowledged influence on Peña—before being divided among other high-security jails. The raid “was an undeniable achievement” and a serious blow to organized crime, said Mabel Rehnfeldt, a veteran investigative journalist for ABC Color. Brazil’s PCC and the home-grown Clan Rotela have long used Tacumbú as a recruiting ground, center of operations, and even luxury retreat.

Unpopular moves

Peña is also courting the international community, having spent a fifth of his time as president abroad on a flurry of 24 foreign trips. But they haven’t seemed to yield significant new investments for Paraguay, Johanna Ortega, a center-left opposition lawmaker, told AQ. “When presidents travel overseas, they need to bring back results,” she said. Important negotiations with Brazil over profits from the massive Itaipú hydroelectric dam, for example, have so far been inconclusive, and conducted behind closed doors, Ortega added.

While Peña projects the image of a modernizing technocrat abroad, controversies are piling up at home. In February, the pro-Cartes bloc in the Senate impeached Senator Kattya González, a high-profile critic of corruption. Her removal—which Peña reportedly opposed in private—sparked street protests and concern from European diplomats. In March, leaked WhatsApp conversations appeared to show prosecutors coordinating with Cartes’ lawyer before they brought charges against former President Mario Abdo Benítez (2018-2023). In April, Peña passed his flagship Hambre Cero law, triggering the largest demonstrations against his government to date. The law ostensibly tackles hunger in schools, but also strips funding decisions from local governments and gives his administration far-reaching control over education subsidies, which students fear will be on the chopping block.

Perhaps the most controversial move came in June, when Cartes allies introduced a bill to impose onerous reporting requirements on NGOs, with heavy financial penalties. The opposition, business groups, the Catholic Church and UN experts have condemned the proposal as akin to civil society crackdowns in Nicaragua and Venezuela. Borda, the former minister, worries his think-tank CADEP—which found that nearly all cigarettes produced in Paraguay are smuggled abroad—and many others will be shuttered.

Cartes, meanwhile, seems increasingly powerful. In July, the Colorado faithful lined up to wish him a happy birthday—a throwback to the Stroessner era—with Peña first in line. “Peña may be the formal president, but everyone knows the real president is holding court around the grill on Avenida España,” said Rehnfeldt of ABC Color, referring to Cartes’ palatial residence.

“Public frustration could lead us down a dark path,” she added. Just last year, radical former Senator Paraguayo Cubas, promising to shut down Congress and shoot corrupt politicians, won 24% of the vote.

Ortega, the member of Congress, warned of a Chile-style social uprising unless Peña starts taxing and spending enough to overhaul Paraguay’s struggling schools and hospitals. “When people have nothing left to lose,” she said, “it’s a bomb that could explode at any moment.”