This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on transnational organized crime.

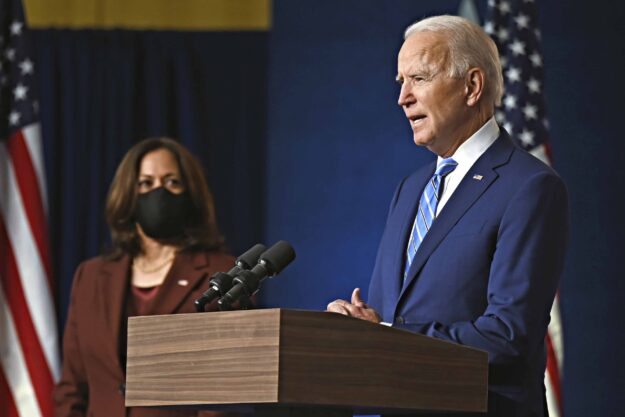

Over the past three decades, Joe Biden has acquired a knowledge of Latin America as perhaps no other incoming U.S. president has. As vice president, he visited the region 16 times. He traveled often to Central America’s Northern Triangle, and during the campaign bragged that he was “the guy who put together Plan Colombia,” referring to the U.S. military and logistical aid package enacted in the late 1990s.

When it comes to U.S. policy regarding organized crime and narcotics interdiction in the region, most expect Biden will largely continue with the status quo that has prevailed during most of his career — and failed to curb either U.S. drug consumption or violence in Latin America. While some changes are possible, the realities of a split U.S. Congress and a crowded domestic agenda will probably prevent the kind of bold experiments such as drug legalization that some progressives support.

“The ongoing opioid crisis is going to make it politically difficult to do anything that looks like softening the law enforcement approach,” said Cynthia Arnson, the director of the Latin American program at the Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars.

Arnson noted that governments in Colombia, Mexico and Brazil seem similarly uninterested in major changes, and also cited “very entrenched bureaucratic interests and inertia in Washington and among U.S. officials on the ground in Latin America.”

However, she and other experts said Biden could act on some of the changes advocated in a major report released by the U.S. Congress in December, written by a bipartisan group of experts and policymakers. The report called for a “long-term, inter-agency” counter-narcotics strategy that would involve greater funding for science-based treatment and prevention, more resources for the Treasury Department’s anti-money laundering efforts, a new drug certification and designation process, and a data-driven overhaul of the metrics for combating drug trafficking and money laundering.

Shannon O’Neil, the chair of the commission that put together the report, expects the Biden administration’s efforts to focus on “citizen security and fighting transnational criminal organizations versus interdicting drugs and focusing on drug trafficking alone.” O’Neil notes that the biggest challenge may come less from partisan clashes rather than from Washington’s complicated processes for enacting policy.

“Lots of different agencies have a role to play,” O’Neil told AQ, “But there really isn’t a corralling mechanism to bring all these together.”

To fix this, the report recommends a larger role for the State Department in streamlining the administration’s anti-crime efforts, as well as locally tailored coordination with Latin American governments.

Collaboration with the U.S. on security and drugs will be particularly vital — and challenging — in Mexico, where “the center of gravity, when it comes to drugs in the Americas, seems to be shifting,” said Bryce Pardo, a drug policy researcher at the RAND Corporation.

Unfortunately, the bilateral relationship has hit a rough patch, most visible after the capture — and subsequent release — of General Salvador Cienfuegos on drug trafficking charges. Shortly after, Mexico’s Congress pushed through a bill proposed by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s office that will make it harder for Mexican officials to collaborate with U.S. law enforcement.

“This could be really problematic,” said Pardo.

Another big roadblock to change, experts tell AQ, is a drugs market that is changing faster than the metrics and tools governments are using to disrupt it.

“Synthetic drugs are the future,” Pardo told AQ. “But everything that we’ve been doing on autopilot for the last 30 to 40 years has really been out of the international drug control regime, which is based largely on plant-based drugs. So it’s hard to shift the policy orientation to be more dynamic.”