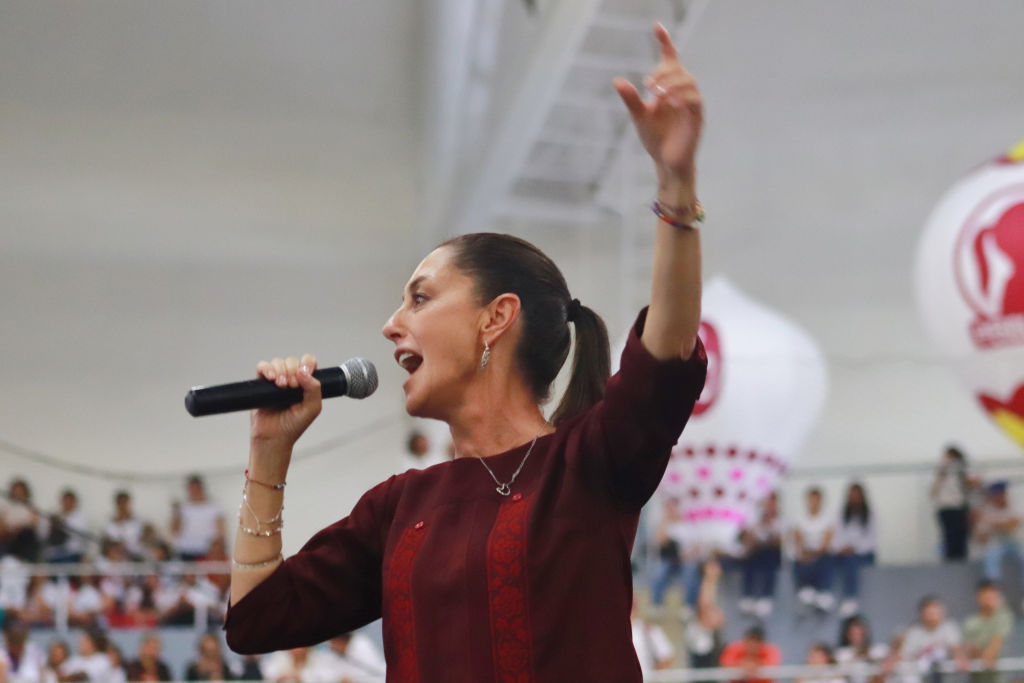

MEXICO CITY — As the presidential candidate of the ruling Morena party, Claudia Sheinbaum is currently the frontrunner to replace Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador in next year’s general election. Though she is a well-known figure from her tenure as mayor of the nation’s capital from 2018 until her resignation in June in order to run for office, her priorities and goals for the presidency are in need of clarification. Onlookers and voters alike are wondering if she wants to continue AMLO’s agenda or modify it in important ways. What’s clear is that if she wins, Mexico’s pressing challenges on energy and fiscal stability will force her to decide one way or the other.

Until now, Sheinbaum has enjoyed a successful transition from the world of the academy to that of politics (she had a successful career in environmental science and energy engineering). She has emulated López Obrador as part of a strategy to garner support among his National Regeneration Movement (Morena), whose hard-core voters follow AMLO almost religiously, although Sheinbaum lacks her mentor’s charisma. With AMLO’s backing, she handily won a recently concluded internal party nomination process.

But soon enough, Sheinbaum will have to take stances on complex and broad topics that might not win the approval of AMLO or his movement. Which raises the question: Who is the real Claudia Sheinbaum? A pragmatist who was able to put in place a first-class vaccine strategy during the pandemic, or an ideologue who followed AMLO’s ambivalent policies, which led to 100,000 casualties in Mexico City alone? A technocrat who understands the importance of data and planning, as when she implemented a successful digital strategy to reduce red tape in Mexico City—or another populist who spends little on subway maintenance and lots on cash handouts for a short-term electoral boost?

Sheinbaum has strong left policy orientations in fiscal, social, cultural, and environmental matters, which are on display when she speaks about climate change and the need for progressive fiscal policy, but at other times, she seems closer to AMLO’s half-hearted conservatism in favoring militarization. She will need to prove her commitment to the rules of the political game and checks and balances—and allay fears she might seek to perpetuate Morena in power. What’s clear is that Sheinbaum has voiced criticisms similar to López Obrador’s of the neoliberal economic strategies implemented by previous heads of state. As such, she’s attributed, on many occasions, Mexico’s significant wealth disparity and elevated levels of violence to these policies.

In the end, from a political risk perspective, what local and international companies, as well as global investors, would like most to know about Sheinbaum is whether, if elected, she will represent continuity with López Obrador in key areas (including energy, mining, infrastructure, health, security, and Mexico’s autonomous public institutions), or whether she will introduce important changes and adjustments to certain critical policies that have been damaging for the business environment. The fallout caused by the new power industry law, the suspension of oil investment rounds, and the cancellation of new private-public partnerships, to name just a few examples, still reverberate.

A complex nation

Whoever wins the presidency of Mexico will inherit a complex scenario—and far slimmer room to maneuver than AMLO enjoyed in 2018. Take two areas: the fiscal situation and energy. The next president will have to deal with strong public spending pressures (pensions will consume 22% of the budget in 2024 considering AMLO’s plans to increase the social pension stipend by 25%), relatively stagnant fiscal income receipts (total fiscal income is barely above its 2018 level), and a past year with unusually high fiscal deficit (-5.4% in its broadest definition) as AMLO is aiming for an expansionary fiscal policy with the precise aim to win the election.

On energy, the story is equally complex. Pemex continues to be a money-losing machine (the Mexican government will end AMLO’s sexenio having pumped more than $60 billion in financial support alone, while the company’s debt will end where it started in 2018, at an unfathomable $110 billion). Current energy policies aiming for energy sovereignty, closing the door for more private sector participation, are making things worse. Mexico urgently needs more and cleaner energy, but current policies seem to go exactly in the wrong direction, with—to add another significant problem—a growing possibility of ending with a trade dispute with the U.S. and Canada.

In both areas, Sheinbaum has signaled continuity: She has stated that she aims to avoid a fiscal reform, hoping that more stringent tax collection policies will be enough to finance her government while continuing to favor the two national energy companies, Pemex and the CFE, as part of the strategy of strengthening the role of the state in energy matters.

The problem with that approach is that both look unsustainable and, in many ways, contradictory. Mexico’s fiscal accounts look shaky at best, with little room for higher public investment. At the same time, current energy policies are opposed in many ways to what Sheinbaum has stated as two of her goals: more reliance on renewable energy and better alignment with climate change international policies.

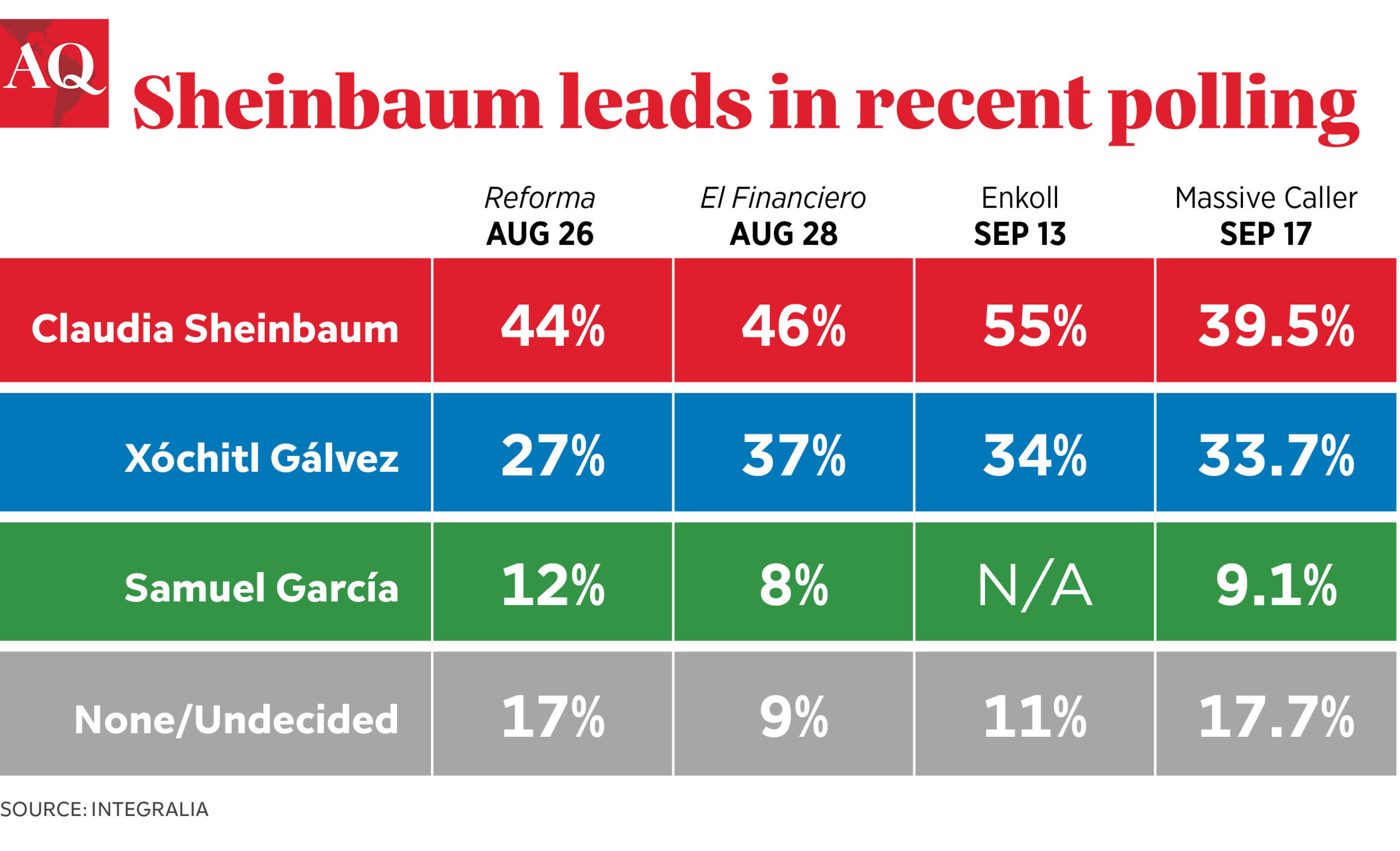

Sheinbaum has come a long way to become the ruling party candidate. Although the election is still open and likely to be competitive, particularly after the nomination of Xochitl Galvez by the opposition coalition, Sheinbaum has a good chance of becoming Mexico’s next president. Today, we know plenty about her biography and roots on the left side of the ideological spectrum but little about her true convictions regarding public policies and democracy. Hopefully, the following months will clarify several of these issues, allowing voters to make a more informed decision and investors and companies to assess their views on Mexico’s political risk for the next six years.